How to apply instructional design models to learning design

How do you start to design an education program? Before any great training course, there were a bunch of sketches in a learning designer’s notebook. Instructional Design Models are frameworks that support learning designers in making sure the products they create are fit for purpose. Think of them as the outline behind those initial sketches.

In this article, we will look at 9 models of instructional design. First we will go through some of the best-known traditional models: ADDIE, Dick and Carey’s model, and SAM. Next, we will add some insights from dynamic training learning models.

We will continue with 3 instructional design models focussing on how to make sure learner motivation remains high. Raising and keeping motivation high can be a challenge, especially in elearning. For each of the 9 models presented, I’ve selected a key learning that can be transferred from that specific framework into any kind of instructional design work you might be doing.

In closing, we’ll add some important notes on what you to take into consideration when working in multicultural settings, given that there is very little in the models to support this part of a learning designer’s work.

Why are instructional design models important?

Think of models of instructional design as scaffolding for your thinking. They offer a starting point, and can be invaluable to make sure nothing important gets lost while working step-by-step on a learning program.

Anyone designing training courses and other learning experiences, whether face-to-face in the classroom or in the virtual environments of elearning, ought to be familiar with at least a few instructional design models. You are likely to gravitate towards one or the other, depending on your ways of thinking, as well as on what kind of content you are working with. Having a bunch of different options at your fingertips will give you the knowledge and flexibility to design and adapt courses that best serve your learners’ needs.

One of my first trainers in facilitation and training design once pointed out that we all have a natural tendency to design courses and experiences that fit our way of learning and thinking. This means that the experiences we craft will work very well for people who share our worldview and style, but might leave other people cold.

Familiarity with instructional design models can ensure that you:

- Have a range of tools to draw from, in order to create courses that fit your learners’ needs, not just your own;

- Design based on time-tested, scientifically sound frameworks upon which to base the different elements of your courses;

- Include all the important elements, decreasing the risk of leaving something important behind in the rush of day-to-day work;

- Know what different elements to add to your course design to make it motivating, engaging, and effective.

Last but not least, if you are working in education you are probably a curious person who might just like to know more about the thinking that grounds most instructional design work today.

3 Traditional Instructional Design Models

As long as there have been teachers and students, there have been ideas and models of learning, aka, pedagogy. That said, when we talk about instructional design we are generally referring to a series of models and frameworks codified from the 1950s onwards, mainly in the US context. The origin of instructional design models is closely associated with three psychological currents (cognitive, behavioral and, more recently, constructivist psychology) and with systems engineering, especially as applied to military training.

Instructional design models arose, in other words, when new scientific research into learning met the need for structured training materials that would be effective regardless of who delivered them. In fact, these frameworks were adopted in military and industrial fields before making their way to education institutions such as schools and universities.

Inevitably, this implies that biases on what learning is, and what learners need, are baked into these classic models. Later in this article, we’ll get back to what that might mean and what learning designers working in multicultural settings might do to adapt these frameworks to contemporary sensibilities.

In the next few paragraphs, we will take a closer look at three “traditional” or “classic” instructional design models. They contain time-tested concepts that are still relevant today. Let’s start with the most basic, popular and timeless of instructional design models: it’s time to meet Addie!

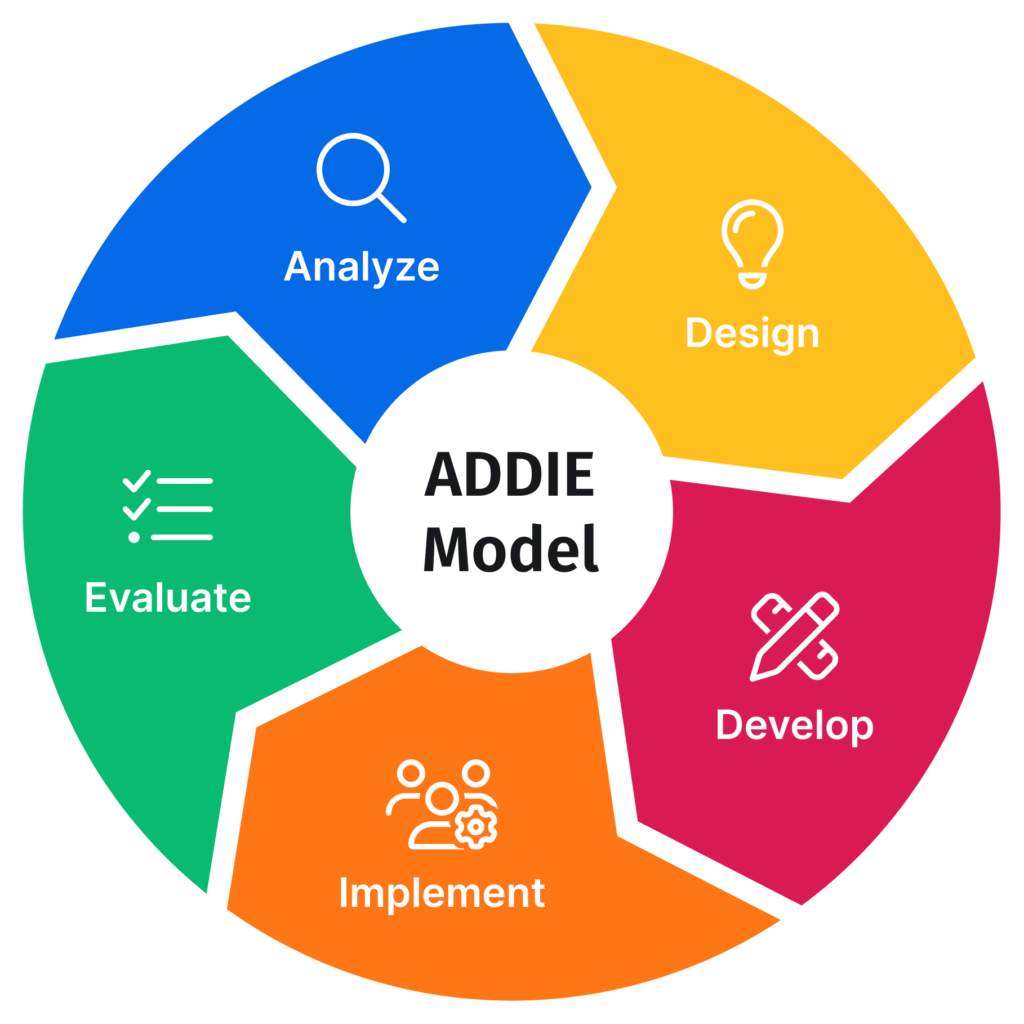

ADDIE model

The ADDIE model is one of the earliest models of Instructional Design or, at least, one of the first frameworks to be explicitly codified as such.

The acronym in ADDIE stands for five steps in the cycle of designing and implementing a training program: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation and Evaluation. The process starts with looking at needs, both the needs of the organization creating (and commissioning) the training course and the learners’ needs, and ends with an evaluation of lessons learned.

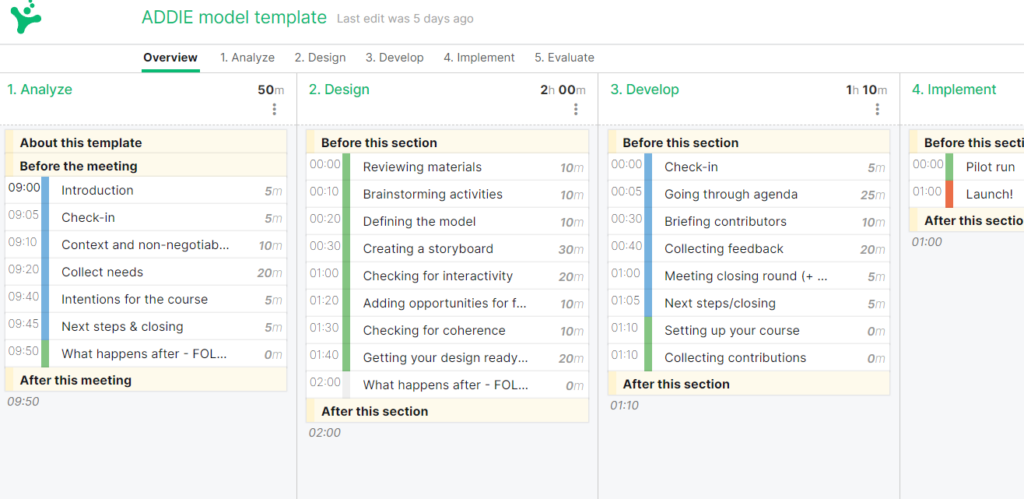

ADDIE is such a well-known, reliable and practical framework that we’ve dedicated an entire learning guide to its workings. I’ve seen it stated that all other instructional design models descend from ADDIE, so if you need a quick flexible guideline to start designing, look no further. You can even start with a ready-made template based on this most versatile of frameworks.

A key learning from the ADDIE model

Go through the design process methodically step-by-step. Start from collecting needs, and weave evaluation opportunities throughout.

Dick and Carey’s Instructional Design Model

Speaking of models that share a lot of their DNA with ADDIE, let’s now look at Dick and Carey’s Systematic Design of Instruction, aka the Dick and Carey model, aka the Carey model (it’s two Careys, by the way: Lou Carey, who together with Walter Dick proposed the original model in 1978, and James Carey, who has been working on later updates of the model—I assume the two researchers are related, but couldn’t find out, so if you know, drop it in the comments please!).

Dick and Carey worked on this model to illustrate ADDIE in finer detail and help learning designers, particularly newcomers. They include 10 steps in their model and invite users to think of these as a whole system, rather than a list of isolated components. This corresponds well to what is likely to happen in real life, where different steps might take place in parallel rather than in a neat, orderly progression.

The 10 steps of Dick and Carey’s Systematic Design of Instruction model are:

- Identify Instructional Goal(s): A goal statement describes a skill, knowledge or attitude that a learner will be expected to acquire

- Conduct instructional analysis: identify what a learner must know and/or be able to do;

- Analyze learners and contexts: collect and analyze information about the target audience, including prior skills, prior experience, and basic demographics;

- Write performance objectives. Objectives should, of course, be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound);

- Develop assessment instruments: how will you test learners’ knowledge before, during, and after the course?

- Develop an instructional strategy: what will activities and content be?

- Develop and select instructional materials, in collaboration with your content providers and subject matter experts.

- Design and conduct a formative evaluation of instruction: what parts of the design and/or content could benefit from some improvements?

- Revise instruction: improve and iterate

- Design and conduct summative evaluation. Close this project and start a new one!

A key learning from Dick and Carey’s model

Different steps of your design work are likely to take place in parallel rather than in a neat, orderly progression.

Rapid prototyping with the SAM model

Instructional design model creators have a soft spot for acronyms. Especially acronyms that sound like they could be people. After ADDIE, it’s time to make the acquaintance of SAM, the Successive Approximation Model.

Perceptive readers might already have noticed a limitation of the two classic models presented so far: it may take a long time to prepare courses following all the prescribed steps. Changing them based on feedback and evaluation could therefore be harder than it sounds, as most important decisions and choices might already be locked in. To include more opportunities for iterative design in your projects, you might want to look at the SAM model.

SAM is a simplified version of ADDIE developed by Michael Allen to highlight the possibilities that come with making design work recursive. Because of its iterative nature, SAM works best for short courses and interventions or, in any case, situations in which your course will likely run over and over again many times through the years.

SAM stands for Successive Approximation Model. It is divided into three phases: Preparation, Iterative Design, and Iterative Development. After gathering information in the first phase, the instructional designer using the SAM model will prepare a quick prototype of the course (a part of a module, for example) and submit it for a round of feedback from representatives of all interested parties (students, content providers, and so on).

Team collaboration is emphasized as an important part of the learning design process. For a deeper dive into the SAM model you can check out this YouTube video.

Photo by Alvaro Reyes on Unsplash

A key learning from the SAM model

Instructional design can benefit from checking in with stakeholders before the final product is ready, to collect feedback and integrate it early, when it’s easy and safe.

3 Learning Models for Dynamic Training Experiences

These classic models of instructional design are invaluable supports to work out the overall flow of learning design work. They clarify all the necessary steps, and will help you be more aware of the workflow involved in creating successful learning courses.

Once you begin storyboarding the details of each individual learning module, working side-by-side with content providers, you might want to turn to some more detailed learning models to help you structure the finer details.

The idea behind many training models is that different people learn in different ways, and it’s the training designer’s job to accommodate this by mixing and matching activities of various sorts. Sometimes the focus is on the senses (visual learners vs kinesthetic learners, for example) others on the way information is absorbed (by discussing, applying, and so on).

In this article on Train the Trainers courses, you can find an overview of learning styles and some discussions on whether such categorizations are even valid. I find them a beneficial way to remind myself to provide multiple ways to engage with any topic and offer learners different pathways and choices to take.

In this section, we will look at three frameworks trainers refer to, that can help you make learning courses engaging for different types of learners. For each, you will also find a ready-made template you can use to see what such dynamic training experiences look like in practice. Using SessionLab’s planner, you can drag and drop sections of these templates to customize them based on your design needs.

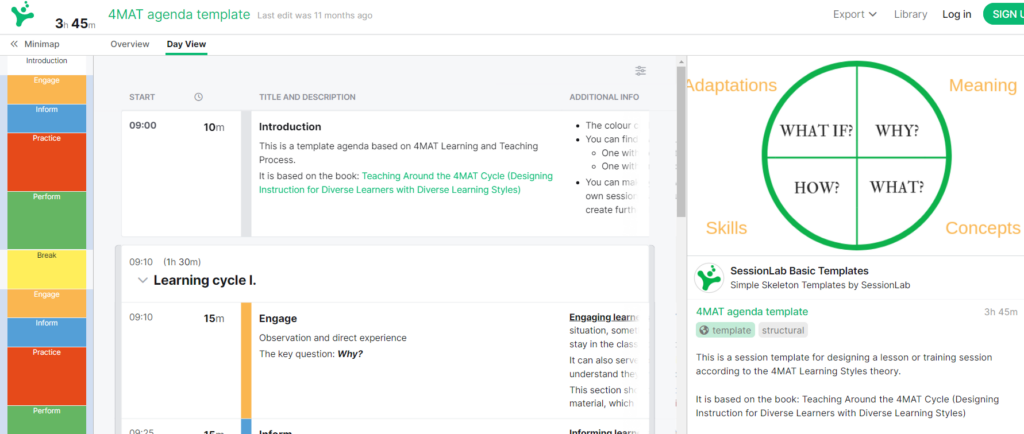

4MAT

4MAT, as codified by author Bernice McCarthy, is a simple 4-step model of how to present and teach new information in a way that caters to different learning styles. Each step features a question, a learning style, and a type of activity.

The first step is about engagement. The key question is why. Why are we learning this? Why is it useful for me? The key here is to find an interesting situation, something that intrigues the trainees, motivating them to stay in the classroom and pay attention for the rest of the time.

The most common type of activity for this step is storytelling. In learning, this might mean starting the course with a video, in which the course instructors provide inspiration to begin with.

The second part of the model focuses on delivering information. Most of your course materials will be at the level of step two. The key question is what. What is the information provided, what should I learn to develop the new skill required? Instructional content for this stage can take many forms including all traditional forms of transmitting knowledge, such as lectures, reading materials, and so on.

Next comes a section dedicated to practice. The key question is how, and this step is about providing opportunities to move from the cognitive to the practical, through examples, case studies, role play and other safe ways to put the theory to use.

The final part of the model deals with performance. How will your learners bring their knowledge into real-world problems? The key question here is What if. What if we did things differently now? What actions will learners take that would have been different before the course? Learning journals and reflection questions are a great way of applying this step in learning.

If you are using SessionLab’s planner for your design, you can even color-code sections for what type of question (Why? What? How? What if?) that particular activity or module helps learners answer.

A key learning from the 4MAT model

Using questions (Why? What? How? What it?) to make order among key sections of your project will bring clarity to a design and help content providers stay on track.

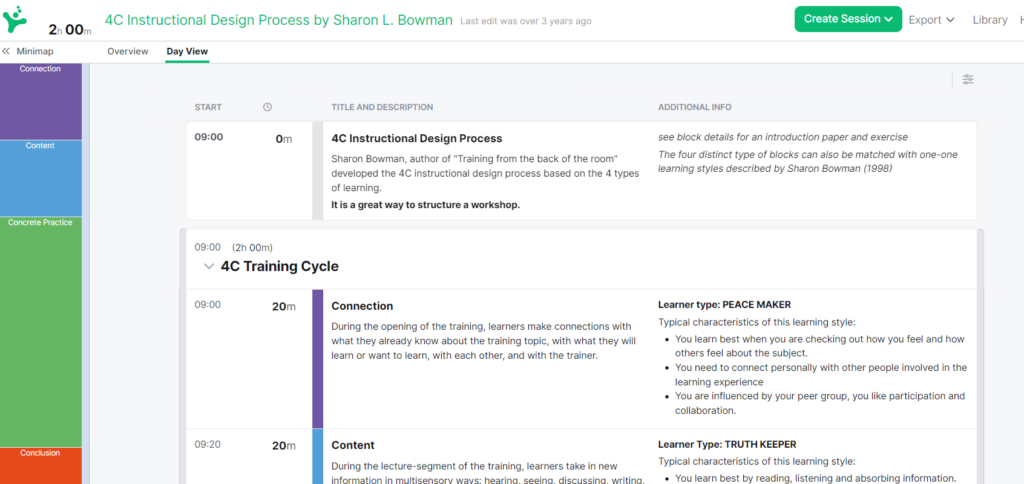

4C

You may have heard of the classic text Training from the Back of the Room, by Sharon Bowman. It’s a great resource, particularly if you are looking to create courses that are centered around the learners themselves, and designed for empowerment.

The book contains another 4-step process based on learning types. The idea here is to start with Connection (making connections with prior learning, with peers and instructors), then move on to Content, Concrete Practice, and Conclusions. The conclusions are centered around action planning.

Essentially, the ideas are quite similar to the 4MAT model, but I find this model easier to apply to online course design. Connection can be established by asking reflective questions to participants, as well as introducing instructors and, if applicable, groups of peers.

Concrete Practice can be achieved through quizzes, assignments and case studies, while Conclusions is likely to take the form of a learning journal or, if your course is blended, a final workshop focussing on action planning.

A key learning from the 4C model

People will benefit more, or less, from different parts of the course, depending on their learning style. Try to include something for everyone.

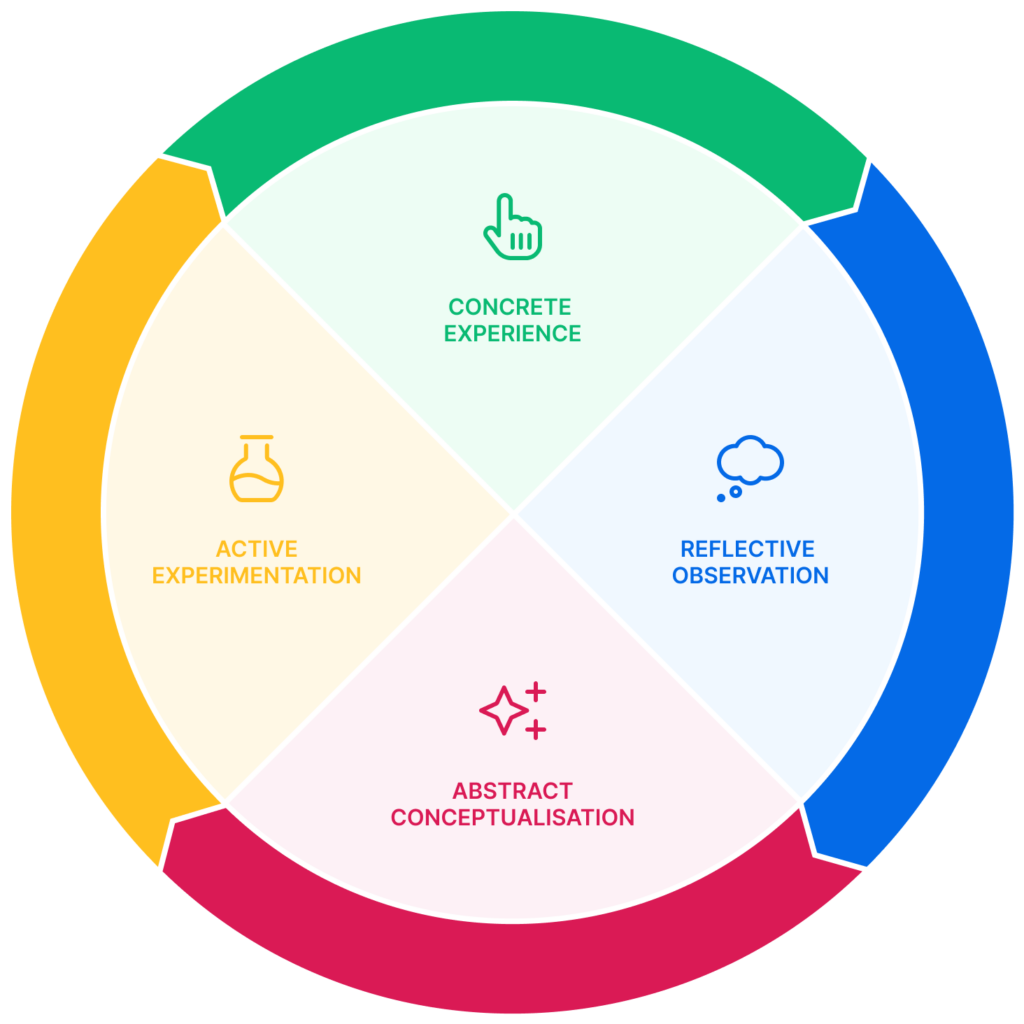

Kolb’s learning cycle

This 4-step model, based on work by American educational theorist David Kolb in the 1980s, is my go-to way to design training and education experiences. It reminds me to make time for conveying concepts and frameworks as well as to start with an attention-grabbing practical activity.

Step 1 in Kolb’s learning cycle is about creating a Concrete Experience to base learning on. Engage learners from the start with a simulation, a roleplay, and exercises that bring your topic to life.

The second step is about Reflective Observation. This is a moment to ask questions of learners. What did they notice during the previous activities? Did they glean any insights? In this type of training program, new knowledge is drawn out directly from participants’ observations.

The third part of the cycle is the one that looks most like “conventional” teaching. Called Abstract Conceptualization, it implies teaching and discussing models or frameworks that students can connect their previous insights to. This is a cognitive learning step where new information is acquired.

Lastly, we come to Active Experimentation, where new knowledge is applied, actually or in a simulation or role play, to real world problems and scenarios.

If you are preparing a learning course, Kolb’s cycle can help you ideate activities that come before and after the main teaching modules, in an order designed to facilitate learning.

What does this look like in practice? Check out a ready-made template for a training session designed based on this learning model, and adapt it to your needs.

A key learning from Kolb’s learning cycle

Start with a game or role play connected to your content: new concepts are easier to integrate if learners have lived through an experience that leads to insights in that direction.

What Instructional Designers can learn from Dynamic Training

Dynamic training models emerged from reflections related to face-to-face education and can be hard to translate to online learning. Moreover, they are often applied in nonformal education settings, and might not be exactly the right fit for academic or corporate training.

Nevertheless, it is my firm belief that all instructional designers can benefit from learning about dynamic training models.

Kolb’s learning cycle might, for example, inspire you to sprinkle real-world challenges in a training course. 4MAT is an excellent reminder to always add the Why. If you fear that your course structure might be too repetitive and would love to add some more stimulation and ensure quality instruction, dynamic training is a great place for inspiration.

3 Instructional Design Models to Raise Motivation in eLearning

As online courses gain more and more popularity, particularly with adult and life-long learning, the issue of how to sustain motivation is becoming central to the discourse. Because there are so many learning opportunities available, and so many distractions competing for attention in our social-media-infused world, it’s easy for learners to deviate from the carefully designed path you’ve laid out for them.

Blended learning designs, which we’ve discussed in this blog article, are part of the solution to the challenge of keeping learners motivated and engaged. Small group learning can help the learning process by keeping participants accountable. Engaging visuals, the use of multimedia (videos, quizzes, visually compelling handouts) as well as facilitation techniques in online and face-to-face workshops are all excellent practical ways to support motivation.

But what about learning design models? Below are 3 instructional design models you can learn from for design that specifically supports motivation.

Photo by Nick Morrison on Unsplash

ARCS model

The ARCS model of Motivational Design was developed by John Keller, an American educational psychologist, to systematize research on motivation and turn it into an instructional model. Much of this work is founded on previous research on the principles that support learning, especially Robert Gagné’s 9 principles or conditions of learning. Read through our guide to his work for more information and practical ideas on how to apply these theories to the practicalities of course design.

The ARCS acronym stands for Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction. According to this model, those four are the main areas we should take care of on the path to supporting student motivation.

The model starts with Attention, arguing that some element of emotional engagement, most notably surprise, is needed to engage participants at the start of a learning experience.

The first thing that came to my mind when I read this was the “wow effect” often felt in a training room if care has been put into arranging it in some way that is different from the usual. Sometimes this is as simple as putting chairs in a circle (To learn more about how room setup can influence learning, you can take a look at this article on room setup.) As for grabbing attention in elearning contexts, which admittedly can be harder, this might mean starting with a video, a story, a “hook” to involve learners from the start.

[…] people are motivated to engage in an activity if it is perceived to be linked to the satisfaction of personal needs (the value aspect) and if there is a positive expectancy for success (the expectancy aspect).

John Keller, 1987

The second part of the model focuses on Relevance. This is about ensuring that the concepts presented are closely connected to learners’ needs and experiences. Relevance is obtained by anchoring new skills into existing knowledge, and understanding how they will be applied.

One practical way to establish relevance, which I commonly use in my training courses, is to ask students, at the beginning of the first day, to discuss what they already know about the topic, and what they would like to learn.

The C in ARCS stands for Confidence. This is about providing measurable, achievable goals, a way to measure progress, and growing levels of challenge. An important part of motivation, according to Keller, is the establishment of a positive expectation that success is possible and at hand.

Last but not least comes Satisfaction. Satisfaction comes from a sense of achievement and is enabled by creating feedback channels where instructors can provide learners with support, encouragement, and pointers for improvement.

The importance of confidence and satisfaction in keeping motivation high has helped me understand, among other things. why some students of mine rebelled against experiments I’ve attempted with giving no grades nor evaluation at all. While it can be good to avoid putting too much pressure on results, knowledge that hard work will be rewarded by an external authority can be very motivating!

Reflecting on the ARCS model and looking at how to incorporate it into your designs can help instructional designers craft courses that keep learners engaged and balance internal and external motivation throughout. Discovering the ARCS model has helped me to understand better why some of the methods and tools I applied to raise engagement were working, and a quick framework of reference to check for new ideas or to confirm I’d cover all important aspects of raising and sustaining motivation.

A key learning from the ARCS model

Design for motivation by including activities and tools to work on Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction throughout the course.

Backward Design

I was delighted when I discovered the existence of backward design as an instructional design model. I was also quite intrigued when I learned of the criticism it has inspired.

Let’s start with what made me happy. Backward Design is a model that stresses designing with the end in mind. The first thing you should do, it argues, is define your learning objectives, then work your way backwards from there.

Backward design is where we get the invaluable sentence structure “By the end of this course, students will be able to….”

This resonated with me for two reasons. First of all, as a process facilitator I am constantly urging my clients to define their end goals and objectives. “Until I know the objectives” I have been known to say “I cannot design a session for you”.

The second reason that made me glad Backward Design is out there is how much it resembles a facilitation method I use a lot, called Backcasting. I’ve used backcasting mostly with community groups to define their long-term goals and work back from those to “what are we going to do tomorrow”. It’s a brilliant way to include wide-angle visions and practical next steps in the same flow.

As I read more about Backward Design, though, I realized that it’s one thing to co-design the future or a session in facilitation, it’s quite another to work backwards as a learning designer or learning design team, without all those other voices in the room.

Backward Design has been criticized for leading to courses that can be quite rigid in their progression (aka “teaching to the test”). There are many learning pathways, and applying backward design rigidly can lead to forgetting about the need for flexibility. Despite the criticism though, there is a lot of value to the Backward Design approach.

In terms of supporting motivation, having a clear end goal that can be explained in two sentences is a great way to motivate participants. In adult education, it’s essential to specify how the course will help participants in their real-world challenges. Backward Design encourages instructional designers to ensure every piece of the course is fit for purpose.

Photo by Kaleidico on Unsplash

A key learning from Backward Design

Instead of starting with the content, start with the learning objectives and figure out, step by step, how learners will get there.

The Kemp Instructional Design model

My introduction to instructional design came in the context of co-designing summer schools on entrepreneurship, targeting Masters’ students in European Universities. The courses’ pedagogy was 100% centered on the learners and we included a lot of peer education and personal empowerment.

This makes perfect sense for a course that aimed to empower young people on the path of entrepreneurship. That pedagogy was probably also inspired by the work of Morrison, Ross and Kemp in defining what is generally known as the Kemp Instructional Design model.

You can envision the Kemp design model as a solar system where everything revolves around the learners. While the actual steps of the instructional design process are akin to ADDIE, if a little bit more detailed, the change is in the perspective taken.

The Kemp model encourages designers to see everything from the learners’ point of view so that their needs, priorities, and constraints are what the course is designed around. This chapter from the Pennsylvania State University’s instructional design handbook gives a good overview of how the Kemp model works.

A key learning from the Kemp model

Design a learning environment and instructional materials based on what you know about learners’ needs, priorities and constraints.

Instructional design models and cultural competency

This last note from Kemp’s model is a good introduction to discussing the relevance of all the models we’ve looked into so far to multicultural groups and in a multicultural environment. Every model since the A in ADDIE, stresses the importance of collecting information on your perspective learners and using this to inform how you structure your course.

At the same time, not very much is included in these models with respect to cultural competency. The models hail mostly from US research, and the traditional or classic ones refer mainly to research made in the 1970s, specifically for the education and training needs of the US military. What does this imply in terms of using these models as lenses through which to view all education?

There are certain biases baked into the models. Learning, for example, is demonstrated by tests and quizzes that imply that the “right” kind of learning has to do with repetition and the acquisition of facts and data. There is also no specific instruction given in traditional models around diversity and inclusion.

Many learning designers have learned to adapt courses to different cultural environments, mainly by developing instructional materials, stories, and images that their learners can see themselves in. This is a great practice, but it is true that it does not require major changes to the structure of the courses themselves.

Photo by Chris Montgomery on Unsplash

What would courses look like if they were designed with multicultural learning at their heart? Authors Charlotte Gunawardena, Casey Frechette and Ludmila Layne have compiled a Culturally Inclusive Instructional Design guide that contains a 10-step list of recommendations for inclusive e-learning design. First of all, the authors invite learning designers to consider their own biases and preferences. What core beliefs drive your design decisions? What do you think is “normal” or “best”? From here, the authors provide more recommendations, such as:

- Acknowledging that bias cannot be eliminated from designs, but that space can be made for alternative experiences, preferences and perspectives;

- Inviting to create space for learners to co-create the course, giving them choices of different learning pathways, and providing options in terms of timelines and milestones;

- Allow for different kinds of learners to shine, without trying to rank them or resolve tensions between apparently disparate or even opposite conclusions. A complex world requires that we learn how to hold different ideas in our heads, all at once.

The authors also recommend learning about, and using, a variety of different instructional design approaches, without getting overly attached to a single or “best” way of teaching, learning and designing. Instructors and designers should know that all of these processes and tools have value, in different contexts and for different materials.

What next?

Hopefully you now feel better equipped to tackle your next learning design challenge. There are yet many more instructional design approaches and principles to learn.

If you want to learn more about the principles behind learning theory, you might find this article on Instructional design principles interesting.

If you feel ready to practice and dive into creating a new course structure, you might want to take a look at a design template based on ADDIE, that you can customize based on your needs.

Let us know in the comments or in our friendly community of facilitators and trainers how your learning design is informed by these, and other, models.

Leave a Comment