We Facilitate: Plans are useless, but planning is invaluable – an interview with Martin Gilbraith, freelance facilitator

Facilitation can sometimes be a lonely profession. Whether you are a freelancer or part of an in-house team, you will often be one of only a few people practicing facilitation and who truly appreciates the value of facilitation techniques.

As Martin Gilbraith, a facilitator with over 30 years of experience noted in our interview: “the vast majority of facilitators work alone or in very small teams and very small practices. Even those that work in big companies are generally the only in-house facilitator or one of a very small team. Mostly, what we do is pretty lonesome.”

Learning from other facilitators and experts in the field can not only help us grow professionally but personally. In the first interview of our We Facilitate series, we spoke to Martin about the world of facilitation and asked some of the burning questions that affect us as facilitators.

We had a great conversation and covered topics such as: the difference between process and content; the value of improvisation when facilitating; how to prepare for unusual or difficult circumstances; how to make money as a facilitator and have a lasting career in facilitation; and the importance of community and spending time with other facilitators.

Let’s dive in!

- What is your definition of a facilitator and what do they do?

- Process vs content.

- Getting started as a facilitator.

- Standout experiences of facilitation.

- On typical lead-times, planning and talking to stakeholders.

- Planning for remote participants and hybrid meetings.

- The value of improvisation.

- The IAF and the importance of the facilitation community.

- Combating loneliness and practicing self-care as a facilitator.

- On having a career as a facilitator.

- How facilitation has changed in the last 30 years.

- On using technology when we facilitate.

- What the future of facilitation looks like.

- Final thoughts.

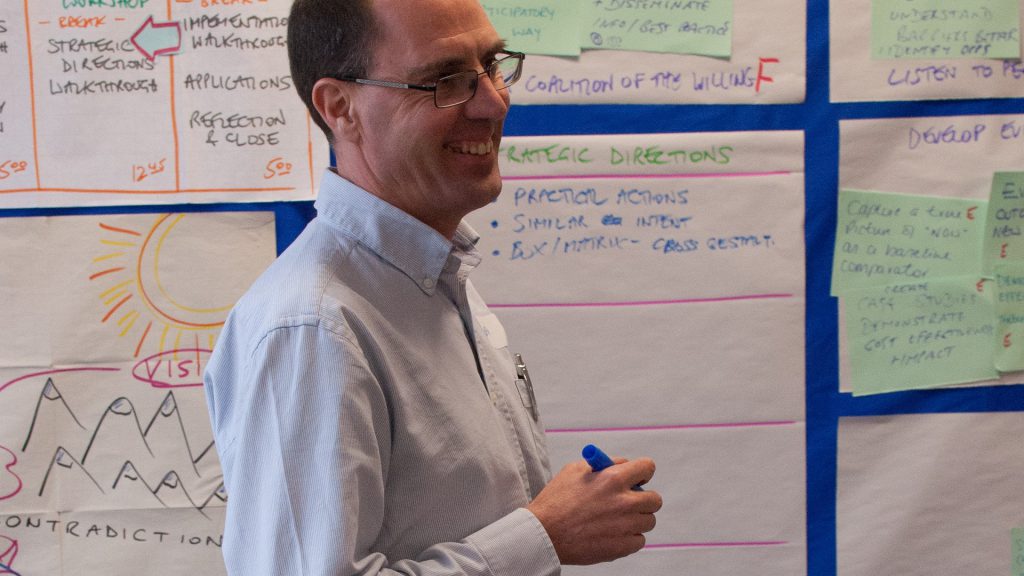

Martin Gilbraith is a IAF Certified Professional Facilitator (CPF), an ICA Certified ToP Facilitator (CTF) and experienced lead trainer and licensed provider of ‘ICA’s ‘ToP’ facilitation training and a Certified Scrum Master (CSM). He is chapter lead for IAF England and Wales and regularly leads sessions in the UK and internationally.

We hope you enjoy the interview!

As someone who’s been in facilitation for so long, what’s your working definition of what a facilitator is and what they do?

Martin Gilbraith: My working definition of facilitation is group process leadership, which is a very broad definition, but my experience of facilitation is that it is a very broad school of practice. It’s not particularly helpful to define it too narrowly. It’s about working in groups rather than individually, it’s about process rather than content, and it’s primarily a leadership role.

It’s about process rather than content, that idea is very interesting, could you talk a little more about that?

The way I see it is that the role of the facilitator is to help a group generate and/or work with their own content. To come out with content that they own themselves, that’s theirs. In order to make that happen, the facilitator needs to stay well clear of content and not get involved in content and instead, design and lead a group through a process to help them generate and manage their own content.

Is it ever a challenge to not get involved in the content creation process as a facilitator? Is that ever difficult to manage?

Not for me, not at all in terms of working with external clients. When it has been more complicated is when I’ve been working internally with colleagues in ICA and with IAF. When we use facilitation among ourselves to do processing and develop content together, the boundaries are necessarily blurred a bit. As long as you all pay attention to what’s going on and are transparent and accountable for what you’re doing, it doesn’t need to be a problem.

I imagine that for any client if one of the outcomes is that they’ve created all of this content for themselves, the sense of ownership is greater and allows that content to be stickier. The work you’ve done in the room can continue afterward because they’ve made something for themselves.

Yes, our role as facilitators is to act in the service of the group. So whatever it is that the group needs to achieve, we’re there to help them achieve that.

That makes perfect sense! Now, I’d like to take a quick step back and hear about how you started and how you got into facilitation.

So I first experienced facilitation soon after I finished my undergraduate degree in 1986. I started with business studies and decided that I didn’t want to go into business so I took a year out to see the world and do something else instead. I volunteered overseas in a community project with this outfit called ICA, the Institute of Cultural Affairs. To cut a long story short, I discovered that, by the end of it, it actually wasn’t a year out: that was the first year of the rest.

The ICA developed facilitation methodology in over 50 years of working with communities and organizations around the world. When I first met ICA as a prospective volunteer, they facilitated me and other prospective volunteers to discover for ourselves what it was that we wanted to do with our lives, what our next step should be, and how we might want to get involved with the ICA. They also trained us in facilitation skills and methods so that we could take a valuable skill with us to the teams that we’d be working with.

At the time they didn’t call any of it facilitation. The word facilitation certainly wasn’t foremost in those discussions: it was about development and leadership. The methods we were taught were called ICA methods and they were described as, you know, this is how we do things in ICA: this is how we organize ourselves, and it’s how we train and support people in communities to organize themselves.

What were some of the communities you worked with? You worked all around the world, right?

I volunteered in a village project in India near Mumbai. I spent six months with ICA and six months traveling. I came back, worked for a couple of years with a small charity in London that was supporting projects in Africa, including ICA projects in Africa, which was part of the reason I got the job. Then I volunteered a second time with ICA in Egypt and wound up staying six years with ICA in Egypt.

For all of that period, I regarded myself primarily as an international development worker specializing in participatory processes, And it wasn’t until quite a lot later that I began to think of myself as primarily a facilitator. It was when I got back from Egypt and got involved with ICA: UK and we began to provide training and ICA methods and sell it as facilitation training. As a result of selling facilitation training, we began to get invitations to provide facilitation as well. So I got into professional facilitation backward by doing the training first.

I suppose that’s the best approach: you’ve been on the ground and have used these techniques in the field. I’ve spoken to a lot of people whose experience is like yours, coming from a different world before becoming a professional facilitator. Is this quite common?

Probably nobody starts their career thinking I want to be a professional facilitator. Most people starting their careers don’t have any idea that there is such a thing or that it’s a career option: and it really isn’t a career option for most people. You really do need to have some experience with the participatory processes somehow, from somewhere, to be an effective facilitator. The vast majority of professional facilitators come at it as a second career after doing something else that moves them into participatory process.

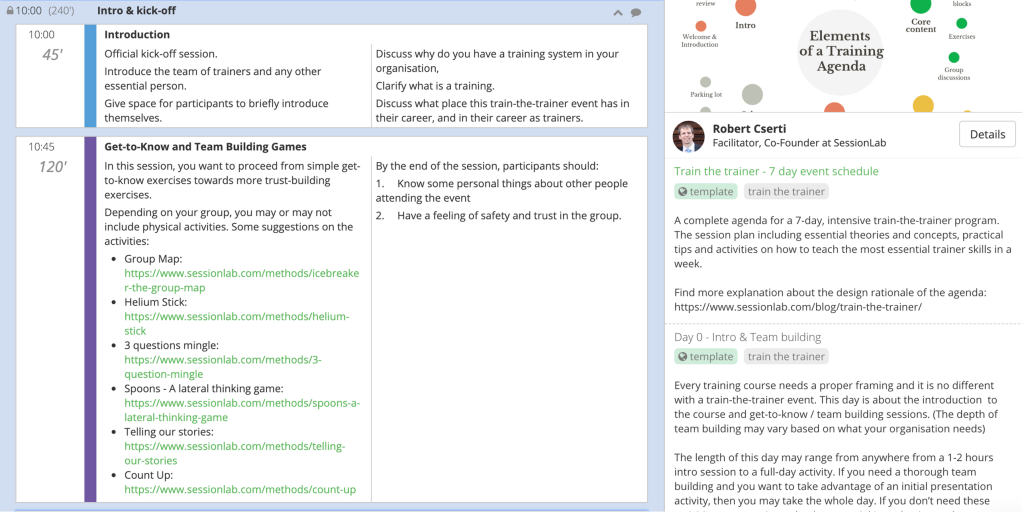

Save time facilitating your next session!

Tell me about one of your most memorable standout experiences of being a facilitator or facilitating?

The best one that comes to mind, which isn’t necessarily the best, but it’s probably the most unusual for me, was facilitating a group of health ministers from developing countries at an international conference.

They have a conference every year, which generally used to be just medical practitioners, and then increasingly, civil society campaigners. In the last couple of years, they had begun to invite policymakers from governments. For the first time they invited health ministers from around the world and they were rather surprised at the last minute to find how many were interested in coming. They got health ministers from Zimbabwe, Mexico, Thailand, all over the world. They wondered what to do with these ministers and went out looking for a facilitator who could come up with some process to make the best of this opportunity.

Most of the work I do is with larger groups – usually much less formal and much more structured. For this group, it was very important to honor the protocol. So there were no post-its, no sticky walls, no toys, none of this kind of stuff. It was basically just conversation for the best part of a day. It was the only group I’ve ever facilitated where the participants each had their own non-participants with them who they were consulting with. So they had their aides with them to support them and provide information. The aides all sat in chairs around the outside, while a participant sat in the center, which was nothing I ever would have considered doing before.

It was really interesting, and they loved it. One of the takeaways from the day was that some of the participants, the health ministers, agreed to make a joint statement on the platform of the main conference of three or four thousand people the next day. That was a really interesting and unusual experience for me.

Every group needs a different process, and I’ve often been in a room and realized some things just aren’t going to work with this particular group. Was that a challenge in this case?

I think that with every group, you need to assume that you don’t know the group. You need to find out as much as you can, or as much as you think you need to know, in order to make any judgment. To first of all best understand them, their goals, and their interests for the session and then to design and lead a session that will help them achieve those goals. Because this group was so different to any other group that I’ve worked with, it was possibly the group that I felt I knew least and had the least chance of anticipating just how it would go and what would work.

Did you have to change your agenda on the fly all or were you able to stick to the plan?

There wasn’t much to change. It was basically a series of questions structured, according to the ICA ToP focus conversation method. What I did do is consult with my client who was the conference director. Together, we discussed what she felt comfortable with and what she thought I should do with them and not.

Did you work closely with her throughout the design process, on the day and afterward presumably?

Actually, the design process happened very quickly. The conference director called me less than a week before the event. We had one or two calls, and most of the conversation design process happened in the 24-hours beforehand when I met went face to face before the conference. So it was very, very short notice, which was the other thing that was unusual.

Do you like working like that?

I wouldn’t choose to, no! I encourage my clients to get in touch as early as they possibly can so that none of us have any surprises and we all have the best opportunity to do the best job that we can.

Do you have a typical lead time for these big corporate events, away days and retreats that might take a long time to prepare?

Most often, I get contacted one or two months in advance for an event of a day or two. Typically longer for a larger or more complex or longer event. But even then, generally not more than 3-5 months. A couple of weeks ago I got contacted for an event next November – around 12 months away! This is a two-day conference with 100 people and part of the reason I was contacted for it is because I did something similar with the same organization a few years ago.

On that occasion, I was contacted two months in advance and I thought we did a great job. I don’t know, three or four months would be great but two months is fine. One month will be doable. 12 months is kind of unusual! I’m not complaining though! The more notice the better really!

Through the lead-in and design process, do you often liaise with just one person at the organization? Or do you try to talk to the larger team beforehand?

Well, it depends on the scale and complexity of the job. But no, typically I try to make sure I’m not just talking with one person. Typically, I try to speak with key stakeholders, particularly the leadership, but also other members of the group. Sometimes it’s also important to talk to people who have a stake that are not going to be part of this particular group.

I do quite a lot of meetings and events which are for a particular team or department where it’s really quite clear who the group is, and the whole group is going to be there. In that case, it’s usually just about talking to the leadership or the whole group, or a few random representatives of the group to get a sense of what the group needs and how they’re likely to respond.

On other occasions, I do quite a lot of work with networks or consortia or alliances where multiple different teams, departments, organizations or sectors are all coming together. And they can have very different understandings and expectations and interests. In those kinds of occasions, it’s very important to talk to a much broader range of stakeholders so that I can show up with a credible process and as a credible facilitator and not appear to be taking one side or being too close to one side in particular.

How do you manage that? Is it a case of just staying in communication over the phone? Or do you have to use any tools or processes you use?

The main way I would manage it is to try to negotiate with the client and discover as far as I can in advance if that kind of approach is going to be necessary and factor it into the contract at the outset. It isn’t always possible and the client isn’t always ready to invest the time and money to do that. Then I have to ask myself whether to take the job or not.

Typically it’s a series of calls. It may also be an online survey using Survey Monkey or something that may also be a shared space where I ask people to upload stuff to look at offer feedback on them. Those are the most common approaches. There are also online meetings – so Zoom calls or Adobe Connect, which is my favorite online meeting tool. Sometimes I’ve done one or a series of online gatherings in the run-up to a face to face event or sort of punctuated in between a series of face to face events.

Is it ever hard to convince clients that this is time worth spending?

Increasingly less difficult actually! Increasingly, I’m finding more and more clients take it for granted, especially international clients. I do work a lot with international groups a lot of them take it for granted that every meeting they ever go to has somebody online, even if it’s not an entirely online meeting. I realized I have to ask clients explicitly upfront: Are you anticipating this to be a hybrid meeting?

Even if we’re talking about a face to face event I make sure I ask, Are you planning on having anybody Skype in for those? Because chances are they are and if I don’t ask, they won’t bother to tell me – they’ll take it for granted. It makes an enormous difference, especially to what the remote participant’s experience is going to be as well.

How do you plan for those remote participants?

I would say it’s largely about managing expectations. It depends a lot on the scale and complexity and the purpose of the meeting. It’s much easier to manage if the purpose of the meeting is information sharing and or people learning for themselves, making their own plans or conclusions.

Trying to bring people to consensus decisions and to build commitment and team spirit is harder to do remotely. And it’s even harder to do in a hybrid basis because the people who are together face to face are having quite a different experience with each other than they’ll have between them and the remote participants.

Is there a secret sauce to making that work?

Lots of advance notice and planning I would say, and also getting the technology right, but recognizing that the technology is just a tool and actually what matters is the process, technology needs to serve the process.

There was an interesting piece of work a few months ago, which was a first for me and quite unlike anything else I’ve done. I’ve done a lot quite a lot of online facilitation and a fair amount of hybrid, holding simultaneously online and face-to-face sessions. But this was the first time that I had been an online co-facilitator for a face-to-face facilitator in a hybrid event.

This was a year-long, hybrid process involving a global nonprofit association with people all over the world who on the whole don’t get a chance to meet face to face very much. We’re embarking on this year-long strategic planning process trying to engage all sorts of stakeholders in developing a new strategic plan. And that developed a dozen or so different working groups who are each having monthly online meetings and three or four times a year getting together face to face, each working on a different piece of the strategy.

For one of the face to face meetings of this particular Working Group, there were three or four of the 15 people who couldn’t get to Europe because they couldn’t get their visas. So the face to face meeting went ahead without them in Europe for three days, and these remote participants in Asia were intending to participate remotely for the entire three days, eight hours a day!

Normally, I wouldn’t recommend anybody trying to do anything online for eight hours at a time! In order to try and make this possible, the face to face facilitator brought me in as a remote co-facilitator so that I could be her partner. I looked after and engaged with the remote participants, and made sure that they were able to engage with what was going on in the room.

It was really interesting because I spent eight hours at my desk and had to be very alert paying attention for eight hours a day to what was going on in somebody else’s meeting and some other place, which is pretty hard to do. On the remote participants, there were only two of them, in fact, and a lot of the time they weren’t there. They joined when they could and I needed to be ready to sort of let them know what they’d missed, to bring them up to speed and to help them to engage. So I had to be very on the ball and ready to engage with participants when I was needed. Though there was lots of time when I wasn’t needed and I didn’t have much to do except to pay attention.

I wonder if this kind of thing is going to be increasingly prevalent in the future and how we might provide those people tuning in remotely with more value. Do you think it was successful for those people who did join remotely?

I think so. I think they felt they had participated as well as they could and that it was a lot better than nothing. I mean, on the whole, I wouldn’t normally design it that way. I would generally aim to get everybody in the room if you want to do that kind of meeting, or otherwise, have nobody in the room and do an entirely different kind of meeting. Perhaps a series of online synchronous meetings with a lot of asynchronous stuff in between.

I guess in those situations where you do get a curveball you have to ask yourself, ‘What’s the best we can do in this situation?’

One of the things I enjoy most about facilitation is that it’s – especially the design but also a certain amount of improvisation on the day – a very creative process. You’re always dealing with constraints and the constraints are all almost always unclear, emerging, and often changing. And it’s always a question of, you know, how can we best understand the constraints, manage them, change them if necessary or desirable, and work within them and do the best we can within those constraints?

You mentioned improvisation – how do you cultivate that? Can you teach that? Is it an innate skill set or is it something you need to learn?

Oh, yes there are people that teach it.

Paul Z Jackson is a very well known teacher of applied improvisation who has written books on the subject. In fact, he did a session at one of the IAF’s recent annual conferences. There’s an applied improvisation meetup with several IAF members involved, with a global network and the UK one. I attended a one-day pre-conference session at the IAF Ottawa conference on improvisation for facilitators which was great. And I hosted a webinar not long ago with one of the leaders of that conference – Rebecca Sutherns – who wrote a book called Nimble: A Coaching Guide for Responsive Facilitation. Which is basically all about how do you keep a group on track when you have to go off script because things haven’t turned out as you expected.

I agree it’s a really important skill because group situations are often so liquid, and there’s always a question of whether you should follow a new thread that emerges at the expense of covering something else. I guess it’s making sure you always have the outcome that you want in mind and only following those left turns that are in service of that outcome.

One of the arguments in the book, which I think is really quite right and important, is that the vast majority of facilitation training and support available is related to facilitation tools and methods. And, I mean, they’re very valuable and important, but they’ll only take you so far.

If you’re lucky, you’ll find training and support and how to design a process, applying and adapting one or various facilitation methods to help a group achieve an aim. But there’s much less out there in terms of training or literature or support in what to do when it doesn’t turn out as planned and how to prepare for that. And it can be learned. Applied improv is a key skill and it can be learned.

Yeah, that’s so fascinating to me, because it’s something that I’ve struggled with as a facilitator. But then you never know with absolute certainty what’s going to happen in the room, right?

I think it’s Eisenhower who is often quoted, and I’ve no idea if this is true, that the plans are useless, but planning is indispensable. I would agree with that completely. The planning or the process of doing the plan itself makes you more prepared for diverging from the plan when that turns out to be necessary. The process of developing a plan and a detailed script for a session helps you be really clear and transparent and accountable for what the goals of the session are, and how you propose to help meet them. And then if it turns out the process isn’t working, or the goals have changed, it enables you and the group to be more easily aware of that and better able to respond to it.

Could you tell me a little bit about the IAF and how you became involved?

So the IAF was founded in 1994 by a network of 70 ICA facilitators. I first got involved soon after I got back from Egypt and went to my first conference in ‘97. A few years later, I decided to get more involved and stood for election to the board at the same time as I went for my CPF (Certified™ Professional Facilitator designation) which was 2008. So I was Europe director in 2009, vice chair in 2010, and chair in 2011 and 2012. Sometime later I took over the organizing of the England and Wales meetups and helped to grow and expand the program of meetups and the leadership team. I’m currently the chair of the IAF England Wales chapter.

How important do you think the meetups are for facilitators and for the IAF?

Increasingly important. It’s where we’ve chosen to put our attention and in England and Wales, my assumption when I started doing the meetups was that – in an England and Wales context – facilitators and facilitation practitioners really don’t need IAF to provide training.

What I thought was that the facilitation profession in England and Wales was sufficiently well established. So where we could best add value was connecting facilitators with each other so that they could decide for themselves what needs to be done to promote the power of facilitation in England and Wales rather than me or some small group deciding for ourselves and doing it.

In some countries, in some chapters, for example, there are only one or two, IAF members and there are hardly any facilitators, and hardly anybody has heard of facilitation. In that kind of context, what they’re doing is raising awareness and providing training. There’s a huge amount available in England, Wales for anybody who is interested and knows how to find it.

What I felt was lacking was kind of an infrastructure of community whereby people interested in involved could connect with each other and do more together collectively for themselves and for the profession.

Do you think this demonstrates a need for a facilitation community?

Well, the vast majority of facilitators work alone or in very small teams and very small practices. Even those that work in big companies are generally the only in-house facilitator or one of a very small team.

Mostly, what we do is pretty lonesome. My experience is probably quite unusual among facilitators in that, having discovered facilitation and developed my practice as a facilitator in the ICA, I’ve always been surrounded by a large and international community of facilitators. Part of what I’ve been trying to do in IAF is to help share that more broadly beyond just ToP facilitators and ICA facilitators, but with the facilitation community more broadly.

I agree! And as you say, it has so much value, as you said, beyond just training and methods. And I think as you say, it’s a lonesome thing. Do you have any advice on combating that sense of loneliness?

Yeah, come to a meetup and meet with other people who do it!

There are a large number of people I’ve met through IAF in recent years who said I’ve been facilitating for years – in some cases decades – and never met anybody else who does it, never knew there was an association, never knew there were professional standards or anything like this and they really appreciated being able to connect with peers and learn and reflect on their own practice in the context of their peers and their peers experience, which can be enormously rewarding.

Yeah, totally. And in all kinds of ways, both in terms of self-care and emotional wellbeing as well as learning to be a better facilitator.

And in many cases, how do I make a living by doing this, how do I make a career out of this? So, it’s very supportive and empowering to meet and learn from others and learn with others who are doing it.

So how do you make a career from facilitation?

Again, my experience is probably unusual in that when I went freelance as a facilitator – that was only seven years ago – I’d already been in facilitating professionally for clients with ICA for 15 years before that. All of what I do as a professional is facilitation and facilitation training, and my experience is that the vast majority of people who make a living from facilitation, they don’t rely on facilitation solely for their living. They also do other things like coaching or mediation or training.

Facilitation for most professional facilitators is a part of their offering rather than the whole offering. Even if they would like to be 100% facilitation, most people start out doing something else as well and many start out not going freelance hundred percent but going part-time into part-time employment and part-time freelance.

I would suggest to work your way into it. Don’t expect to make a living as a professional facilitator 100%. When you’re 21 and starting a career, that’s not how it works. It takes time.

Is word of mouth still the best way of getting clients?

Yeah, for me, it’s the vast majority of my clients. Well, I think all of my clients come from word of mouth, either face to face or online. Face to face is largely people that I have worked with before and then talking with others, or it’s, or its people I’ve met in various networks come to know me that way or have spoken with others. Online networking through social media and through other online forums is also important. You get to know people that way and they talk with others as well. It’s basically all about getting known.

Do you think your online presence is a big part of that?

I would have thought everybody in any kind of business needs to have an online presence these days. Especially if you’re in a one-person business, like me, or a very small business. I do know people who facilitate who don’t have a website and don’t use social media. Not many, but there are some. I guess it depends to some extent on your business model.

For me, my clients, and my contracts are almost all pretty small by some standards. I do a lot of one or two-day gigs. I’ve very rarely had more than 10 or 15 days. My biggest contract is probably 50 days, and that was over a year or so. Some people I believe, have had one or a very small number of very large contracts where facilitation may just be an element. In that case, you may not really need much of an online presence, but you might find you’re very reliant on that one contract or that one client and if it comes to an end or falls through then, you know, where does the next one come from?

Are there any things you should never do as a facilitator?

I’m not much inclined to tell people what they can’t do. Certainly, don’t be unethical as a facilitator. We have an IAF code of ethics and a statement of values. Though I would say do be ethical – I prefer to frame it in a positive light.

But in terms of what not to do, part of what that means is don’t try and do something that you can’t do well. Don’t lead your group to a foregone conclusion, don’t manipulate.

When you say foregone conclusion, is that in terms of what the group or client expects and wants the conclusion to be, or both?

Whether it’s you that thinks the group needs to come to a particular conclusion or whether you’re taking the lead from the client to lead the group to a particular conclusion, either way, it’s not facilitation if you’re trying to lead them to a particular conclusion. Which isn’t to say that you shouldn’t do it. It’s just that you shouldn’t call it facilitation.

Yeah, that’s a very different thing. Have you ever had clients have this kind of misconception about what facilitation is?

I’ve only quite rarely experienced that. But I’ve heard other facilitators saying that they experience that more commonly. Maybe to some extent, it depends on how clearly you articulate what it is that you do and how well known you become for what you do. Then you’re more likely to attract clients that are looking for what you do not, and not for something that you don’t.

You’ve been in facilitation for a long time. More than 30 years – how has it changed in that time?

The impact of technology is an obvious one. The internet didn’t exist when I met ICA and first got trained in ICA methods. I don’t know if you’re familiar with sticky walls but ICA ToP facilitators are famous for using sticky walls that didn’t exist when I first learned. We used rolled up bits of masking tape in order to stick bits of paper to Blackboards or that kind of thing.

So technology has made a big difference to what’s possible and to what clients are looking and groups are looking for. I suppose the professionalization of the field is another big change. IAF you know, is 25 years old, and so it didn’t exist when I started out and has grown and changed a lot in that time. That’s had a big impact on the profession.

It’s interesting what you say with technology. Do you use high-tech methods and tools yourself? Or do you quite like low-tech? Do you think paper and pens and post-its will always have a place?

I absolutely think low tech will always have a place. I favor what works on the whole. I’m very conscious that for anything to work, a group needs to be sufficiently familiar with it so that they’re not spending all their time learning the tool rather than getting on with what they’re there to do.

The tool shouldn’t be an impediment to them connecting with each other and accomplishing their task. Now, if you’re working with a remote group, then you know there’s no alternative to using technology, even if it’s a conference call.

If you’re working face to face, you know there are times when digital tools can add a lot to that and help people to do a great deal more than otherwise especially with large groups, you know, hundreds or thousands at a conference. With small groups, I tend to avoid digital tools because I tend to find it unnecessary. Anything a digital tool can do can be done just as well without the digital element, and often a lot quicker and with a lot less distraction and a lot less risk of failure or confusion or distraction or whatever.

Do you favor a particular low-tech tool? Are you a post-it note man or do you like flashcards or Lego?

More than anything else, I use sticky walls, papers and marker pens. And in terms of method, more than anything I use ORID, which is the basis of the ICA focus conversation method. Yeah, so pretty much every question I ask will be crafted in relation to an ORID process that I have in mind.

I’m a big fan of just whatever works too! And it’s a case of you can sometimes overcomplicate or try a flashy new thing just for the sake of it being flashy. We have to ask, what are we trying to achieve here? Are we trying to demonstrate we have some new tools, or do we want to have a good outcome? On that note, what do you think the future of facilitation is going to look like?

Now that’s an interesting question. In a future of artificial intelligence and robotics and all the rest of it, just about every job is under threat. I would like to think that facilitation is one of the few jobs that isn’t under threat. What they say is that jobs that require empathy and caring and human interaction are the ones that are safe. And facilitation is right up there with those. Though I did see something online in the last few months about some algorithm that somebody has developed to facilitate, which is scary and is something I’m rather skeptical about, I have to say, but who knows?

The future is unknowable. But then again, at the same time, it’s ours to create and I’m in the business of helping people decide what kind of future they want and go about making it happen. So whatever way technology is going to take us, I think it’s up to us to decide how to make the best of it and how to turn it to our benefits and interests.

I completely agree! Is there any final bit of advice you want to give people involved in facilitation or to those considering getting involved in being a facilitator?

Do it!

I’m a firm believer that facilitation is a public good. I got into facilitation in order to try and change the world for the better one way or another. And given the way that the world is going, I think the world needs more and more facilitation in order for us as communities, societies, and as the human race, to survive and thrive into the future, so we need you, facilitators! And be sure to connect with each other in order to do it better and strengthen our impacts collectively.

Yeah, I totally agree. That’s awesome. Martin. Thank you so much for meeting with us and sharing your wisdom with the community!

Martin Gilbraith is a IAF Certified Professional Facilitator (CPF), an ICA Certified ToP Facilitator (CTF) and experienced lead trainer and licensed provider of ‘ICA’s ‘ToP’ facilitation training and a Certified Scrum Master (CSM). He has been a facilitator and trainer since 1986 and has been providing facilitation, training and professional consultation to clients since 1997. He began his career in grassroots community development work in India, Africa, and the Middle East, after awakening to his passion and commitment as an international volunteer. Since 1997 he has worked with a wide range of clients in the UK and overseas as a facilitator, trainer, and consultant and you can reach him on his website.

Better tools = better facilitation

We hope you enjoyed reading our interview with Martin as much as we enjoyed conducting it!

Was there anything you found particularly interesting or would like to hear more on? You can help us shape We Facilitate with interviews and content that is most useful to you!

Want to take part in our We Facilitate series or have a recommendation for who we should interview next? We’d love to hear from you!

Leave a Comment