Key Takeaways

A brief visual summary of key findings

Demographics & Employment

Who is in the room and what this tells us

Facilitation Practice

Inside the work: topics, frequency, formats

Welcome to the fourth edition of SessionLab’s

State of Facilitation report.

Our topic this year is impact: how is the impact of facilitation assessed, evaluated and communicated? Read on to find out.

Facilitation is often described as powerful, transformative, and essential, but these claims are not always easy to substantiate.

As organizations face increasing pressure to justify time, budget, and attention, facilitators are being asked new questions about impact. What did their intervention change, why did it matter, and how can the impact be demonstrated?

The 2026 State of Facilitation Report turns its focus to these questions. Based on a global survey of facilitators working across roles, sectors, and experience levels, the report examines how impact is currently understood, measured, and communicated in practice. It highlights common patterns, emerging practices, and persistent challenges, alongside reflections from experienced practitioners.

This report is not a verdict on what the impact of facilitation should be. Instead, it offers a snapshot of where the field stands today, and an invitation to strengthen the habits, structures, and conversations that help facilitation create lasting change.

If you are a freelance facilitator or trainer, this report offers concrete ways to think about impact beyond “a great session.” You’ll find patterns from peers on how to assess outcomes, talk about value with clients, and build credibility over time, especially in ways that support sustainable consulting and repeat work.

If you are a manager or leader who commissions or sponsors facilitation, this report helps make the work more legible. It sheds light on what facilitators actually do, what kinds of outcomes different sessions support, and where impact tends to appear, both immediately and over time. It can help you ask better questions, set clearer expectations, and make more informed decisions about when facilitation is worth the investment.

If you use facilitation as part of your day-to-day job (e.g. in project work, team leadership, product, or operations) this report provides concrete practices to help you reflect on what is working. It offers ideas for small, realistic ways to improve clarity, follow-through, and learning without turning facilitation into an extra layer of process.

Across roles, the report is designed to support a shared conversation. For example, there is a notable gap between professional L&D monitoring and evaluation practices and what the facilitation community is currently doing. Resources on assessing impact specifically for facilitation are lacking. Knowing where we are at can help us see what’s needed, and what’s ahead for 2026 and beyond

4th edition

714 respondents

60 countries

Answers in 8 languages

English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian and Russian.

10 expert thought pieces

A brief visual summary of key findings

Who is in the room and what this tells us

Inside the work: topics, frequency, formats

The why, how and what of assessing facilitation’s impact

What helps create impact, what hinders it, and how to learn more

What facilitators say, what clients hear, and what gets lost

Prefer to download the report?

If you prefer to download the report in PDF format, leave your email here to receive it in your inbox. You’ll also receive SessionLab’s facilitation newsletter and get updates about the next survey.

Before we jump in, a word of caution:

To collect responses we reached out to our networks, colleagues, business partners, and friends. We did our best, but inevitably that reach is limited. A majority of responses reached the survey through our own channels, such as the SessionLab newsletter. This may help explain certain aspects of the data we’ve collected, especially when it comes to overrepresentation of European and North American responses.

Help us reach beyond our bubble in the next edition by joining in and reaching out to your networks. Leave your email below and we will let you know as soon as survey for 2026 is open.

43.9% of facilitators assess their work in order to improve their own performance. Reflective practices, alone or with co-facilitators, are widespread. This is great practice, but not an impact measurement.

Fewer than 1 in 3 facilitators has agreed on measurable performance indicators with their clients. Without clear business outcomes defined at the contracting stage, impact assessment tends to become retrospective and uncertain.

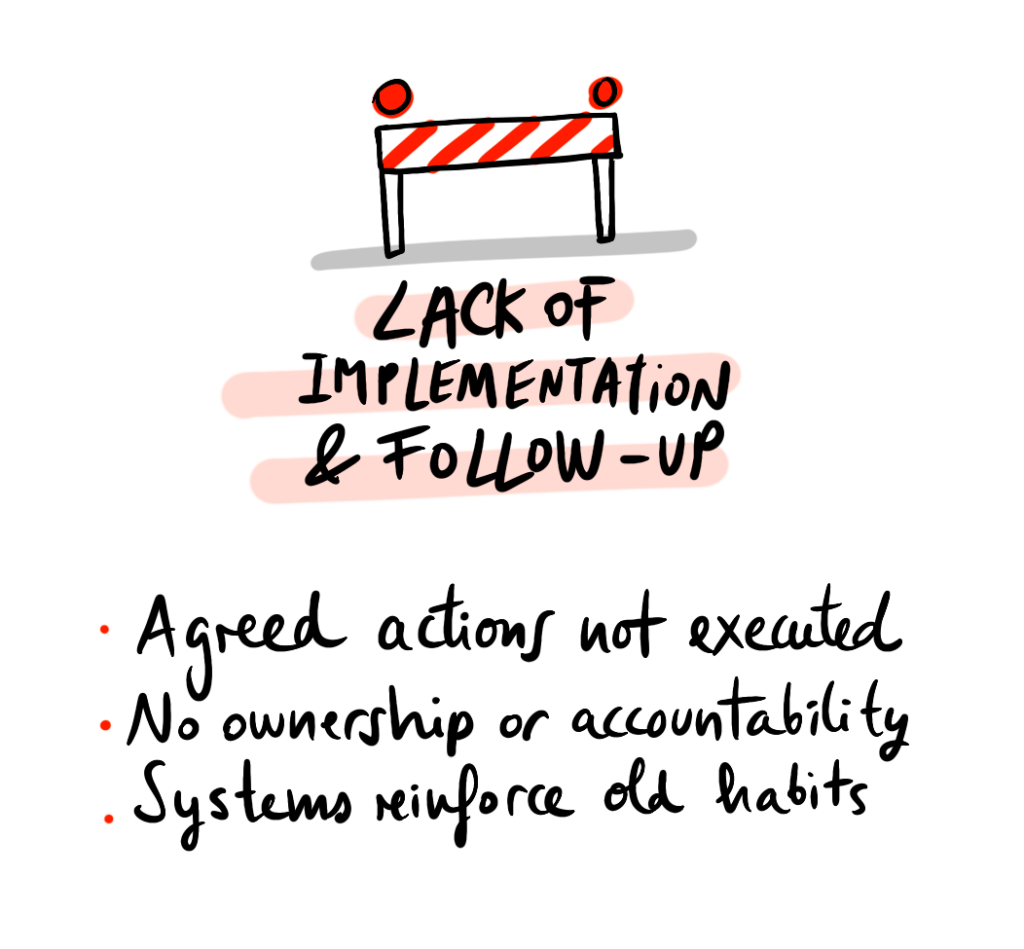

Many sessions are evaluated based on engagement during the session, but their true impact is shaped by what happens (or doesn't happen) afterwards. 43.5% of respondents stated that the main barrier to impact is a lack of follow-up conversations.

As facilitators gain experience, their focus shifts from satisfaction to sustained outcomes and follow-up. Experienced facilitators are more likely to integrate follow-ups, debriefs and needs analyses into their process.

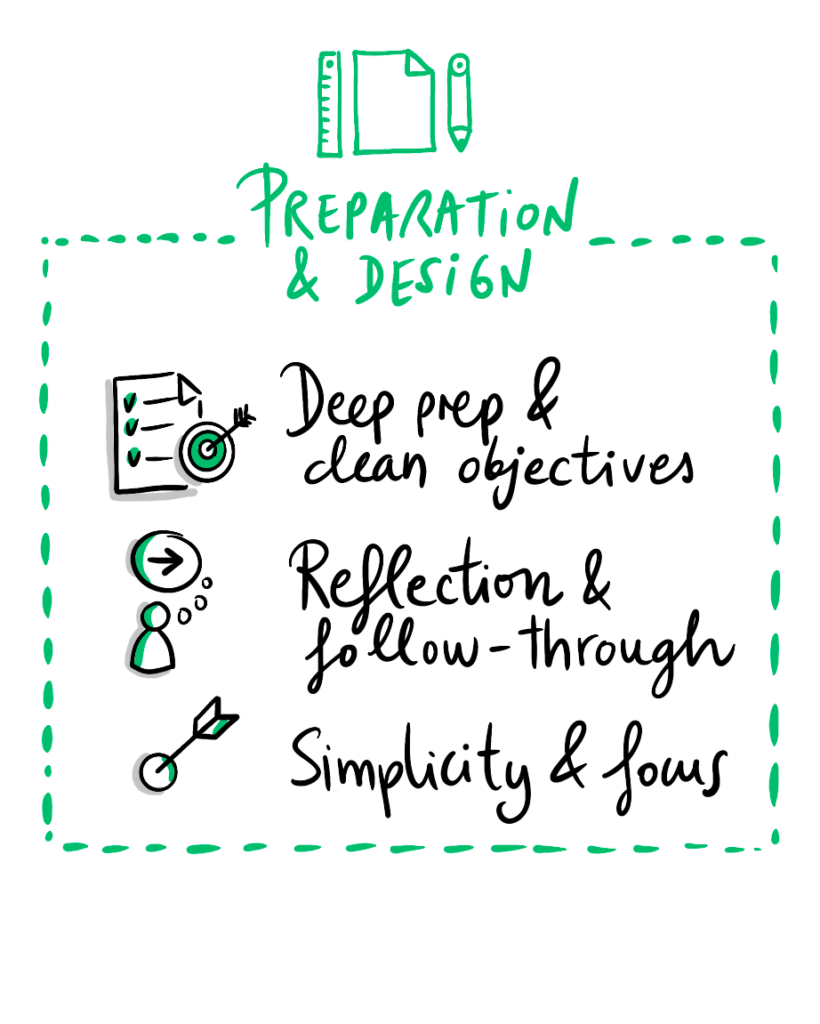

Evaluating impact starts long before a session begins. Questions about impact should be discussed in advance of a session, and the story of what happened and what changed should follow. Considerations around impact should come at every stage of the process, not as a last-minute add-on.

The way facilitators talk about their craft and the way clients and team experience can seem like different languages. The challenge for the field may well be less about impact itself, more about making that impact more visible and more widely understood.

Let’s start by checking where the data for this year’s report comes from. In the next section, we look at who has responded to our global survey about facilitation: their backgrounds, experience levels, roles, and how they enter the field.

These patterns matter because they shape the possibilities and limitations of facilitation: who finds their way to this work, whose voices inform its evolution, and where the next generation of practitioners may (or may not) emerge from.

Understanding who is in the room is the first step toward understanding the field itself. This is also data needed to contextualize the rest of the report: we do our best to make it representative of the global reality of facilitation, but that said, it’s important to know where the data skews.

The age distribution this year shows a higher proportion of mid-career facilitators responding to the survey (the 50-59 cohort is the largest, with 33.4% of respondents, and the youngest cohort has decreased from 3.6% in the past edition to the current edition’s 2.1%).

This reflects the chosen topic for this edition, with impact tending to be a greater concern for practitioners with several years of experience. While newer facilitators may not yet be focused on impact and value, we hope this report offers guidance that supports them in developing these practices earlier in their careers.

The geographical distribution of responses again reflects the reach of our own networks, with the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada topping the chart. While representation remains strongest in North America and Western Europe, we are encouraged to see growing engagement from countries such as India, Singapore, and New Zealand, indicating a more interconnected global community.

As in past years, these results remind us of the limitations of our sampling and the importance of continuing to build bridges across facilitation communities worldwide. Thanks to everyone who is supporting these efforts, including by sharing our yearly survey.

And to the 1 person per Country who answered from Argentina, Belize, Cambodia, Colombia, Estonia, Iceland, Iran, Jordan, Kiribati, Lithuania, Mexico, Niger, Norway, Pakistan, Qatar, Taiwan, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates and Zimbabwe: thank you, it’s good to hear from you. We hope it’s not too lonely facilitating over there!

Facilitators come in all shapes and sizes, and call themselves all sorts of things. There are those who use facilitation skills but consider themselves mostly trainers (34.4% of respondents) or L&D professionals (30.4%), and many prefer using the label of consultant (42.6%).

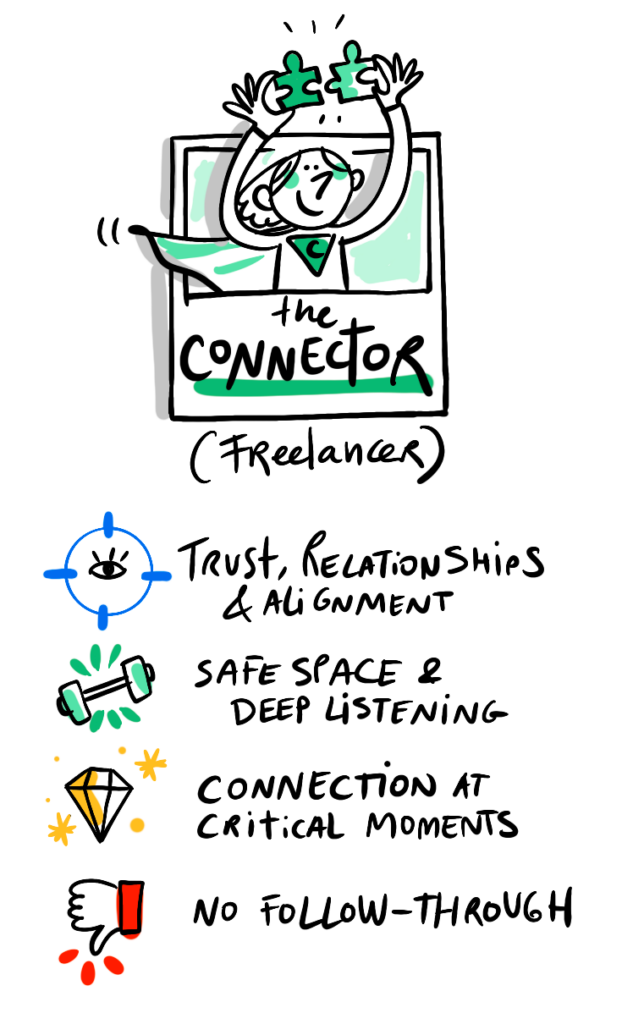

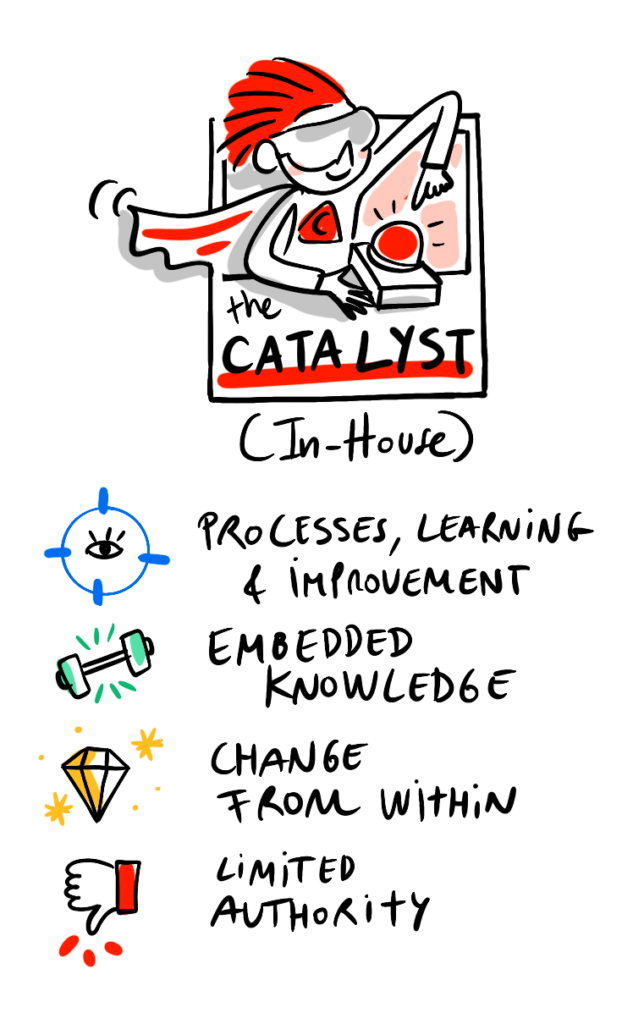

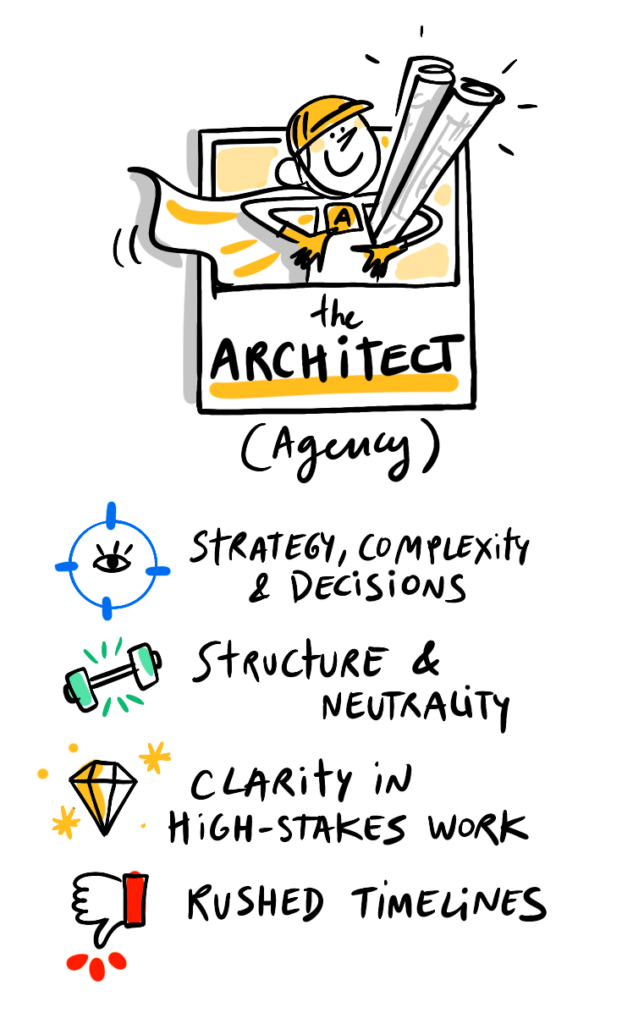

To try and capture some of the diversity of the facilitation market, we’ve asked people to indicate whether they mainly work as freelancers, as part of consultancy/facilitation agencies, or in organizations where facilitation is part of the work but is not the main service provided (aka in-house facilitation).

Independent facilitators make up the largest share (44.4% of our sample). As we know from the previous graph, many respondents blend facilitation with roles in training, L&D, coaching or organizational change.

In-house facilitators form a smaller segment (29.4%), typically working in people-focused functions. Among those who named their sector, most operate in education and tech companies (23.7% and 18.4%), followed by healthcare, energy and manufacturing—fields where collaboration and participatory processes are already central.

A third group (23.5%) is formed by practitioners who work as part of an agency or consultancy dedicated to facilitation.

We’ll be using this categorization throughout the report to highlight differences in how these roles work, think about impact, and communicate value. In the visual harvest below we have captured some overall patterns that come from responses given by people in these three roles throughout the entire survey.

Participants who indicated they work as in-house facilitators were asked to add the sector their company operates in. We think this graph should put old-fashioned ideas that facilitation only exists in certain industries to rest. Education (23.7%) and technology (18.4%) top the chart, but we can see how facilitators are working in practically every type of industry (and there were so many different sectors and unique responses under “Other” that we couldn’t really aggregate those results).

In-house facilitation is everywhere.

The distribution of experience levels remains broadly consistent with past editions, though this year’s focus on impact appears to have attracted a slightly more experienced cohort (68.1% experienced, compared to 63.8% last year). Beginners remain a small portion of respondents (6.5%), a pattern seen across all years of the survey. This mirrors the age distribution and suggests that conversations about impact resonate more strongly with mid-career and senior practitioners.

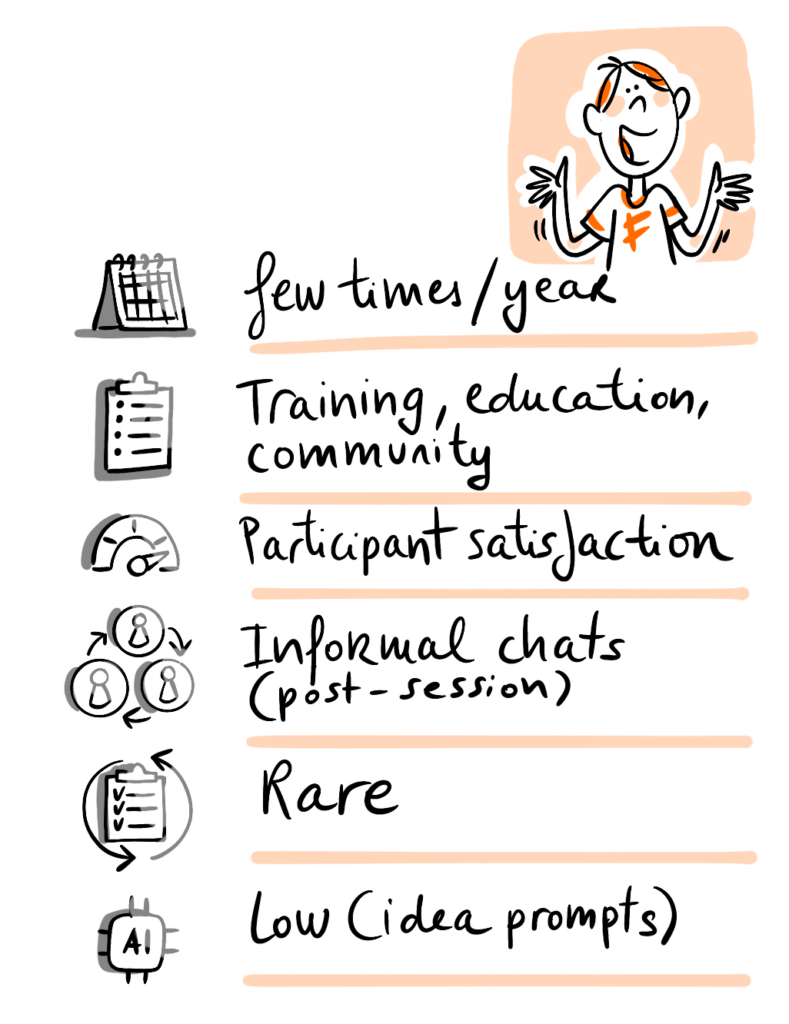

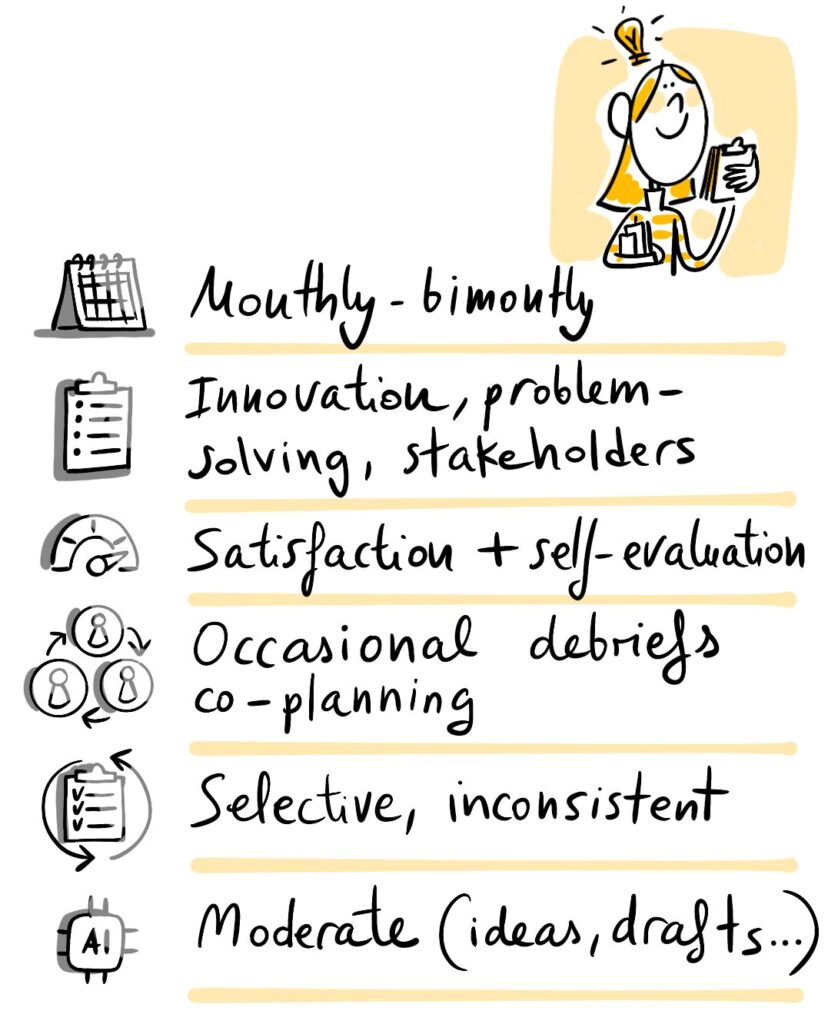

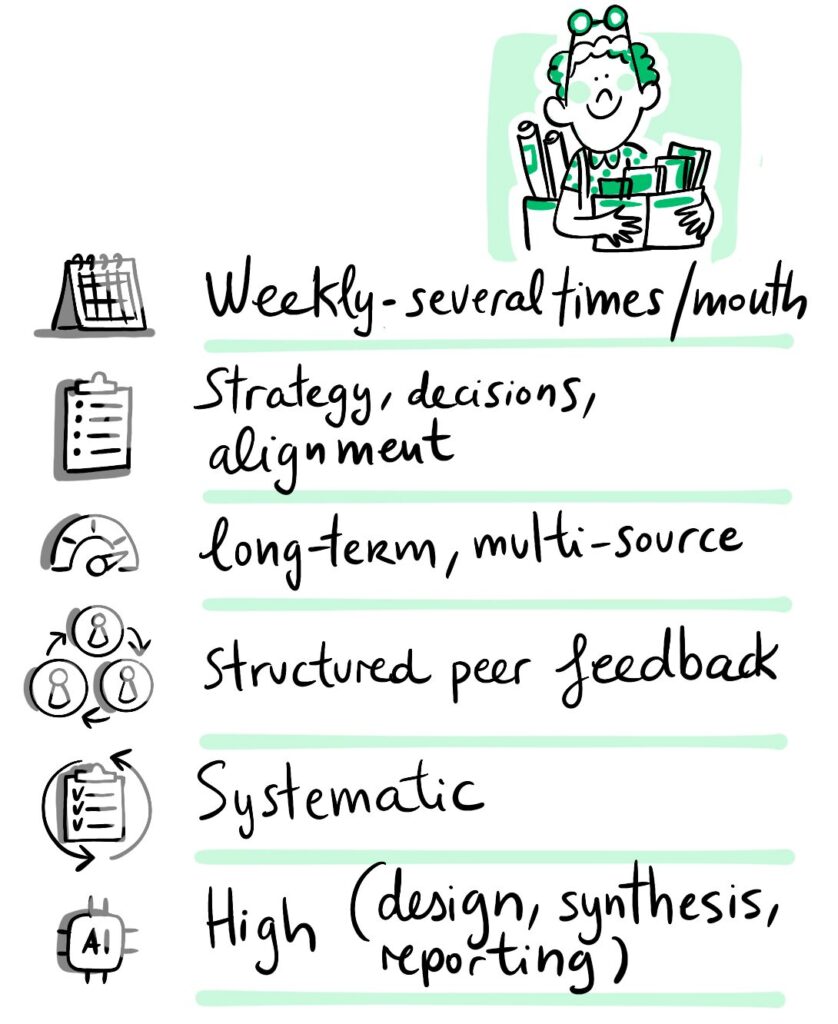

We’ve used the distribution and correlated it with various answers found further in the report to create this (simplified, reality is always more complicated than a survey can capture!) of how facilitation roles progress over time and experience.

Data collected throughout the survey outlines a clear maturity arc in how facilitators work, evaluate success, and collaborate.

Beginners tend to operate in training or community settings and measure success through immediate participant satisfaction (their top motivation across the group). Intermediates broaden their portfolio, leading more innovation and problem-solving sessions while beginning to reuse agendas and apply structured feedback.

By contrast, experienced facilitators run the most complex sessions and adopt multi-dimensional evaluation practices, including long-term follow-ups and stakeholder interviews, which appear in their responses far more often than in other groups. They also make greater use of generative AI tools for tasks such as agenda design and data synthesis, indicating more confidence in orchestrating end-to-end facilitation workflows.

These differences point to the skills that matter most as a facilitator’s career progresses: moving from content delivery to process design; from one-off sessions to cumulative practice; from satisfaction scores to meaningful indicators of behavioral or organizational change; and from solo delivery to collaborative reflection.

The survey suggests that the facilitators who advance furthest are those who develop strong habits of evaluation, co-facilitation, and systematic reuse of prior work. There are practices associated with deeper professionalization and with the ability to deliver sustained impact over time. As facilitation matures as a field, these skills form the backbone of a strategic, evidence-informed practice capable of influencing change at scale.

The certification landscape continues to diversify. LEGO® Serious Play and ToP (Technology of Participation) are the most common structured programs. A growing share of facilitators report no formal certification (47%) or identify training from a wide variety of sources (33.6%). IAF accreditation saw a modest increase, suggesting steady interest in globally recognized professional standards.

The “Other” category masks a significant amount of informal or adjacent professional training. When aggregated, coaching certifications (3.3%), design/creativity programs (2.2%), Agile or Scrum facilitation pathways (1.7%) and academic credentials related to group dynamics or participatory processes (1.7%) all register as meaningful clusters. This suggests that facilitators often develop their skills through broader professional identities (such as coaching, design, innovation, and project management) rather than through facilitation-specific accreditation.

The picture that emerges is one of a field with multiple entry points and learning pathways rather than a single unified accreditation route.

Demographics: What They Reveal About the Facilitator Community

Every year, the State of Facilitation report offers us a mirror as a way to see not just what we do, but who we are. Each year, the demographic trends offer important insight into how the field and the people in it are evolving and changing, giving us a glimpse into where the field may be headed next.

This year’s report confirms what many of us have sensed in our peer networks: the facilitator community is largely composed of mid- to later-career professionals, with a significant concentration in the 35–54 age range.

This reflects a broader truth that facilitation is often a second (or even third) professional chapter, discovered after accumulating years of meaningful life and leadership experience.

Rather than a barrier, this later-career entry is a strength. Facilitation thrives on pattern recognition, emotional intelligence, and adaptive leadership, all capacities honed over time. Many facilitators arrive at this work after navigating complex roles as educators, strategists, community leaders, or changemakers.

In that way, the demographic profile reveals something unique: facilitation is a calling, not just a career, often fueled by a deeper desire to make a positive impact.

It also opens an important question: How might we encourage earlier entry into the craft of facilitation?

While the field is growing globally, the data shows it remains concentrated in a few regions and cultural contexts. As technology enables our tools, platforms, and training communities to scale across borders, there’s both an opportunity and a responsibility to ensure this growth is inclusive, representative, and attuned to diverse worldviews.

The report also highlights distinct facilitator profiles: Consultants, Coaches, Trainers, Educators, and Internal Practitioners, each bringing unique orientations to the craft. These overlapping roles remind us that facilitation is rarely practiced in isolation. It complements and amplifies other forms of leadership, teaching, and organizational development.

And yet, the data also shows that a majority of facilitators work as individuals, not within formal teams or companies. This reveals a powerful data point, and also a tension.

Inside the xchange community, we often say: “Never design alone. Never facilitate alone.” These mantras reflect a cultural shift toward collaboration and co-creation. The prevalence of solo facilitators highlights both the autonomy of the role and the growing need for peer networks, communities of practice, and collaboration ecosystems to support sustainability and excellence in the work.

Finally, the data tells us how facilitators skill up. Nearly half of all respondents report no formal accreditation or training certificates, while just over one-third have completed a formal training or certification.

This signals an important opportunity: to make high-quality, accessible, and inclusive training more visible, and more widely available around the world. As the field grows, so does the demand for trusted pathways to mastering the craft.

What does this mean for the future of our field?

Bottom line: Facilitation is being shaped by a generation of experienced professionals choosing meaningful, human-centered work. As the field evolves, we have a shared opportunity to support each other, both in what we do and who we are in the world.

Steve Bouchard heads training and client relations at xchange, a leader in designing and facilitating transformational learning experiences that unlock human potential in teams, communities, and companies. xchange offers training and certification programs for change agents that enable them to revolutionize how we lead, teach, and convene by using The xchange Approach, both online and in-person.

Steve Bouchard

Let’s turn to what facilitators are actually doing in their work. In the next section, we look at the kinds of sessions practitioners are leading, how frequently they design or run them, and the formats they rely on: online, in real life, hybrid, and increasingly, blended.

We’ll also look into which types of sessions facilitators think of as most impactful, why, and what practitioners mean when they insist that the best format “depends” (In case you didn’t know, “it depends” tends to be facilitators’ favorite answer to most questions).

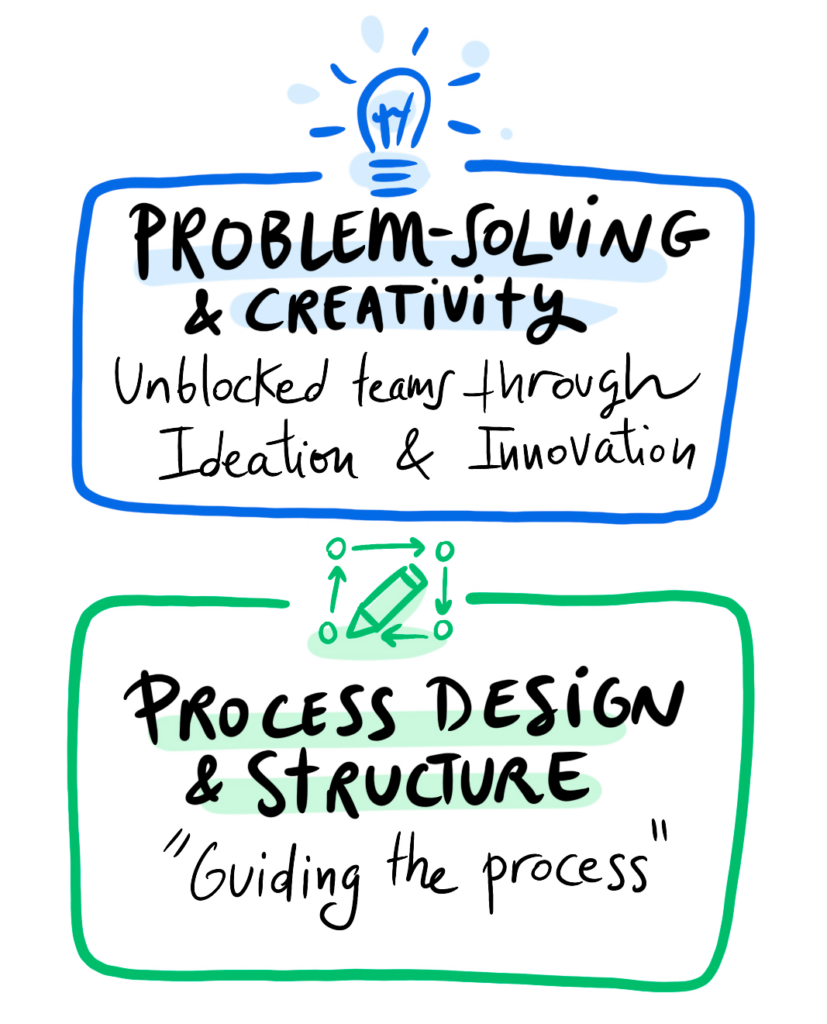

What topics did facilitators most contribute to in the past year? The top 3 is occupied by team development, training in soft-skills, and strategic decision-making or planning sessions. We enjoyed seeing how that squares neatly with the most-used templates in SessionLab’s Library, as team development, training, and strategy are the most commonly-researched topics.

Some interesting patterns emerge by looking into the breakdown by facilitator role.

Freelancers focus heavily on team development and collaboration (61%) and soft-skills learning (53%). Their work helps teams reconnect, strengthen relationships, and build the human foundations that support performance. Organizations often bring in independent facilitators when they need fresh energy, trust-building, or leadership development that benefits from an external voice.

Agencies and consultancies are most active in strategic planning and decision-making (49%) and stakeholder engagement (20%). These higher-stakes sessions demand neutrality and structured support to align diverse interests and move complex work forward. Here, facilitation directly supports clarity, agreement, and organizational direction.

In-house facilitators focus on project and workflow-related sessions (29%), technical or capability-building training (21%), and innovation or problem-solving workshops (45%). Their work strengthens internal processes, builds skills, and supports ongoing improvement—core activities that help organizations function and evolve from the inside.

Taken together, these patterns show how facilitators contribute across different layers of organizational life: with the risk of simplifying, we can say that freelancers nurture people, agencies enable alignment, and in-house teams drive operational and strategic progress.

Unsurprisingly, frequency increases with experience: beginners work sporadically, intermediates establish a steady monthly rhythm, and experienced facilitators operate at a continuous weekly cadence (with 38% of practitioners designing sessions a few times per month or more). Employment type also shapes intensity: agencies show the highest weekly activity (25%), in-house teams maintain consistent monthly practice, and freelancers’ workloads vary more widely.

Together, these patterns show how organizations rely on facilitators differently—agencies for fast-paced cycles of strategic work, in-house teams for ongoing internal improvement, and freelancers for key developmental moments.

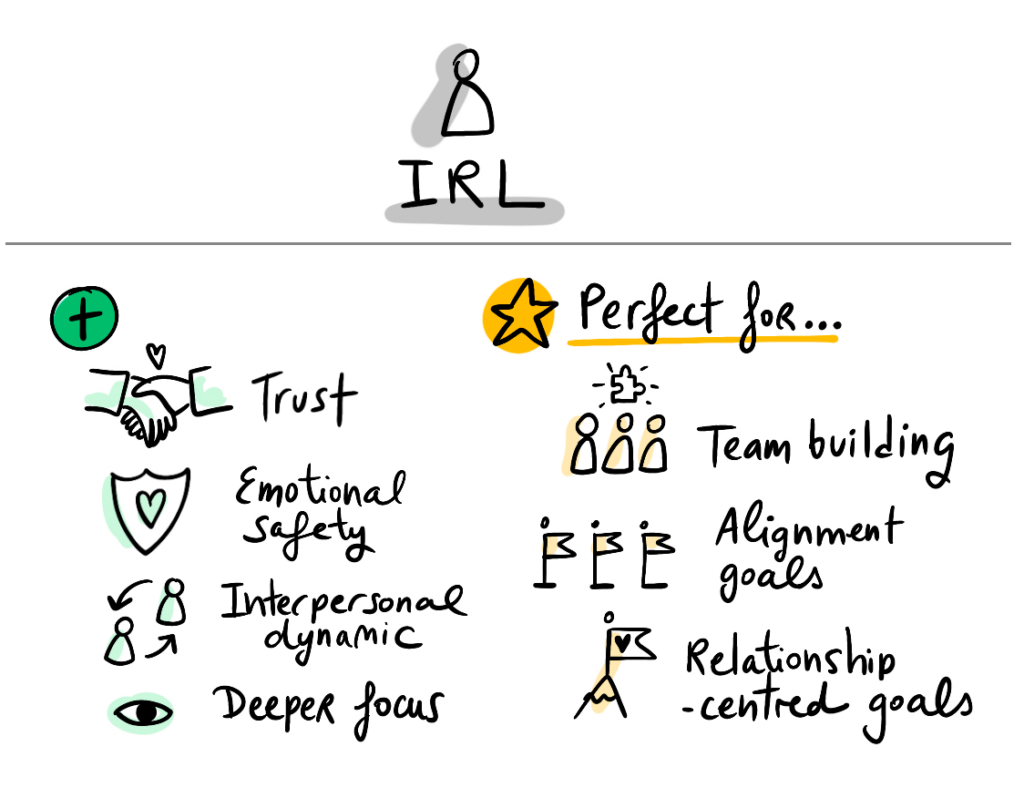

After the disruption of the pandemic years, the ratio of in-person to online workshops seems to have stabilized, with a slight upward trend for in-real-life events. Hybrid events, with some people joining in-person and others participating remotely, remain infrequent.

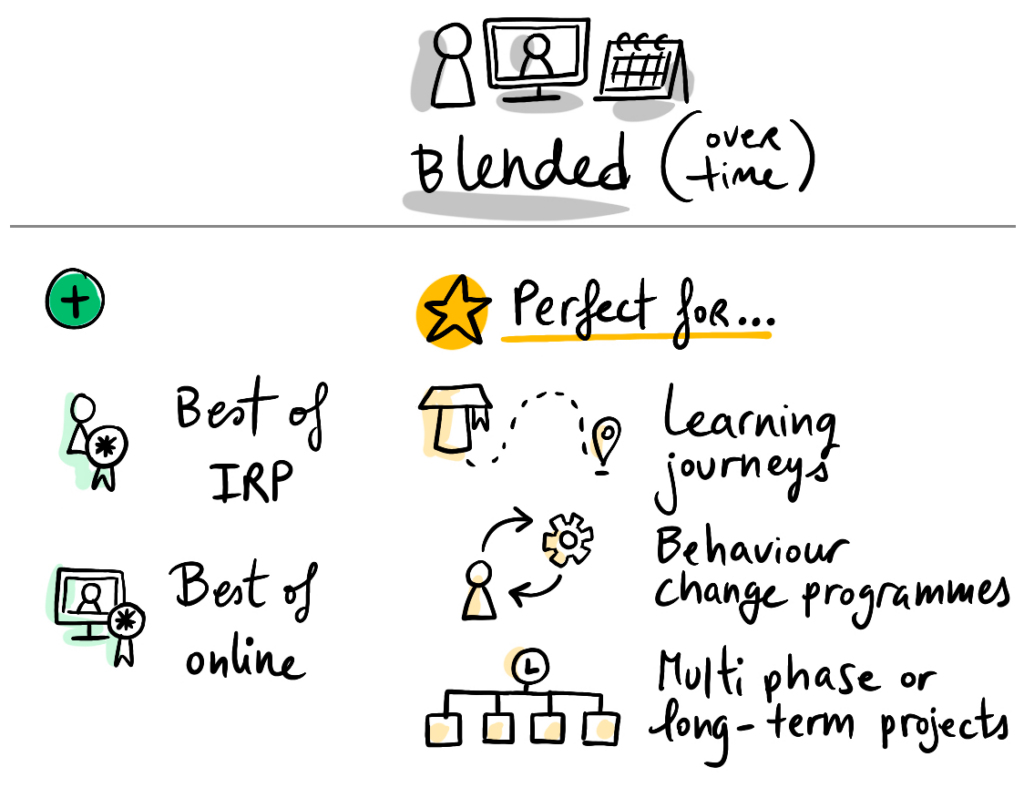

We will see with the next questions that facilitators are increasingly advocating for blending in-person and remote sessions in longer programs which may also contain some self-paced elements.

In 2026, facilitators need to know how to adapt to different contexts, honing both the “reading the room” kind of skills so essential to in-person sessions and the technological proficiency required in online environments.

Furthermore, facilitators need to know how to guide clients in the choice of format, including notes on how hybrid sessions require higher investments in technology, staff, and preparation work, or explaining why a blended program might offer the best chance of making an impact over time.

Which types of sessions do practitioners believe deliver the most impact, and why? We think this is an interesting and important question, as it might guide choices on what sorts of programs to set up and invest in. Let’s see what respondents said.

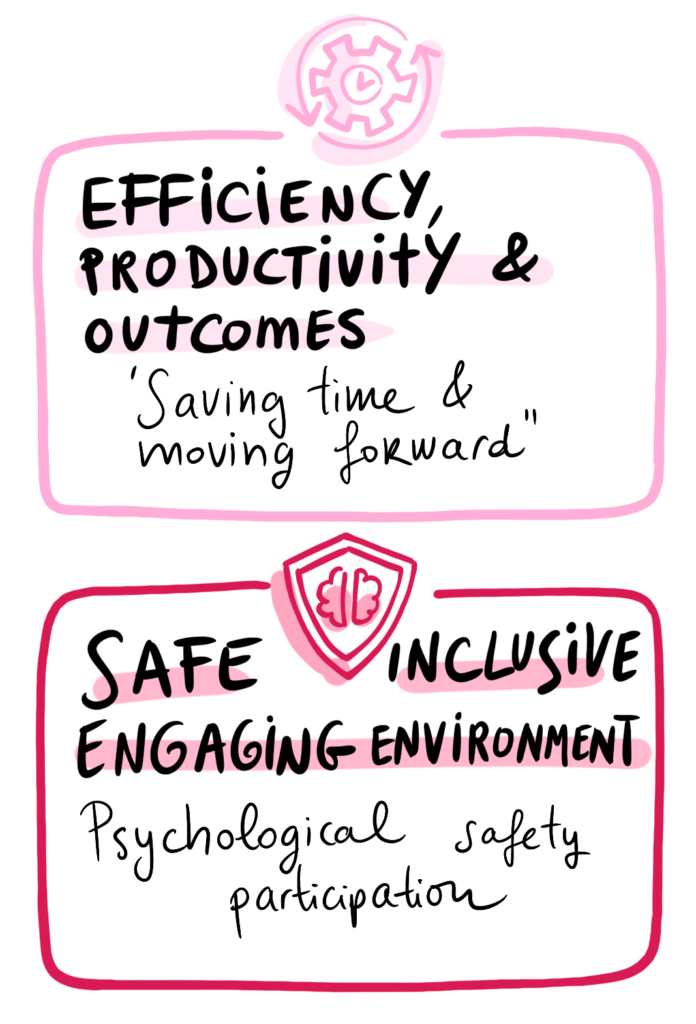

In-person sessions are considered more impactful in general (51.3%). When asked to explain why, facilitators consistently described in-person sessions as the most impactful for work that relies on trust, emotional safety, or nuanced interpersonal dynamics. People mention comfort, presence, reading the room, informal moments, deeper focus, and more consistent engagement.

In-person setups are seen as particularly effective for team building, alignment, and relationship-centered goals: situations where subtle cues, energy shifts, and shared physical space meaningfully influence outcomes.

Online formats, however, are valued for their inclusivity, ability to connect distributed teams, reduced travel, and suitability for technical or content-heavy training. They allow more voices to be included, offer accessibility benefits, and conserve organizational resources. 33.4% of respondents consider online formats the most impactful kinds of session.

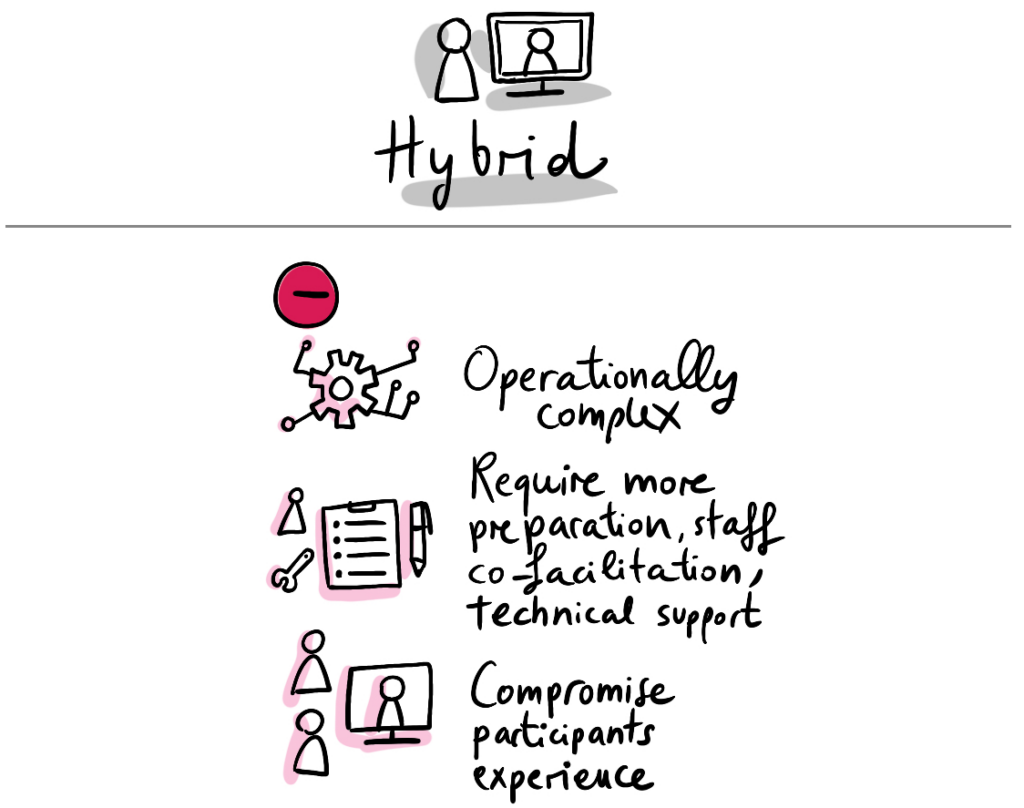

In contrast, hybrid is overwhelmingly described as the “least loved” format. Respondents emphasize the operational complexity (more staff, more preparation, more co-facilitation, stronger tech requirements) and a persistent sense that hybrid compromises the experience of at least one side of the room. For many, it is used not because it is desirable, but because circumstances force it.

10% of facilitators highlight blended programs as a particularly effective solution. A common pattern here is to pair high-impact in-person workshops with ongoing online touchpoints, such as virtual check-ins, learning modules, participant commitments, and follow-up reflection. Respondents describe this combination as offering “the best of both worlds”: depth, trust, and momentum from in-person sessions, and continuity, practice, and scalability through online components. Blended design is seen as especially useful for learning journeys, behavior change, capability building, and multi-phase projects, where a single format cannot meet all needs.

Those who answered “it depends” specified that they refer to a needs-based decision process shaped by the client, the participants, the objectives, available resources, and the constraints of timing and geography. Many respondents take a principled stance that format should follow purpose. In-person for high-stakes team dynamics or deeply relational work; online for efficiency, inclusion, and training; hybrid only when circumstances make it unavoidable and with the awareness that it requires significantly more design attention.

Several responses hint at a more emotional undercurrent: some facilitators appear strongly attached to defending in-person formats, no matter what, especially due to the limitations of “reading the room” online.

That said, most emphasize adaptability, intentionality, and alignment with goals, choosing the format that best supports outcomes rather than personal preference.

In person events are fantastic to bring people together, but are time-intensive; online makes it easy to participate, but lacks on the connection sphere.

A combination allows us to reach a wide variety of stakeholders and create trust/personal links at the same time.

It is so dependent on the participants.

Previously my response would have automatically been 'in-person' however now I've adjusted that as I recognise that some people are much more comfortable when they're online as they feel less exposed.

All in person is too intense.

All online is hard to connect.

Blend the best of both worlds.

If human connection is high on the outcomes list, then face to face works well.

If on the other hand the outcomes are more business/strategy focused then virtual works really well.

During in-person events one has the possibility of reading the room and the participants in a profoundly different way than online.

I think some people don't choose online because they don't know how to fully leverage the tool, but blame the fact that it is online.

We like to say "people don't have zoom fatigue, they just have bad meeting fatigue."

There are certain topics,such as collaboration, trust, relationships, and communication, that are undoubtedly best addressed in person, in an offline setting. However, there are also many topics that work perfectly well and effectively in an online format.

Words are hard. They mean a LOT of different things to different people, don’t they?

Take this word, for example: “workshop.”

Some people think it means training. Some people think it means facilitated collaboration.

Some people think there will be physical tools involved — you know, hammers or sewing machines and such. Some people call their thing a workshop, but it’s really a PowerPoint presentation.

That’s probably why this report is brought to you by SESSIONLab and not WorkshopLab.

Looking above, in this report, at the kinds of sessions we’re all running, and the formats we’re all using, and the many many many instances where “it depends” — it feels like the meaning of “what a workshop is” gets even fuzzier.

But you know what? It doesn’t matter.

The different topics, frequency, and formats aren’t the important part.

The ONLY thing that matters is the outcome. That’s what people want, need, and pay for.

If the same outcome could be achieved by swallowing a pill, or reading a book, or implementing new software, or asking ChatGPT, or hiring a consultant to do it, or plugging their brains directly into the matrix, then people would do that instead.

A workshop happens to be a tremendously effective, fast, and fun way to get to that outcome. And that, dear friends, is why we love workshops so.

But remember, some people (gasp) don’t actually like workshops.

It’s like “people that don’t like ice cream.” It makes no sense, but they exist.

The topic of this year’s report is IMPACT. So let me say it again.

It’s. Not. About. The. Workshop.

(Or. Session.)

It’s about the impact. The outcome. The results. The transformation. The ROI.

Which brings us back to words, and why they’re so hard.

In general, facilitators aren’t great at articulating the value of what we do. Yeah, yeah, I’m stereotyping. There are exceptions. But on the whole, we aren’t great at it.

We like to talk about what we do. We like to talk about how we work with our participants. About how we’re paying attention to all the diverse voices and creating psychological safety and all the stuff that WE know is important.

But that’s not the impact. That’s how we get there.

To create value, our words need to describe the impact. The group is currently “here,” and we will get them to “there.” A transformation is happening, not just a session.

Let them EXPERIENCE the magic of the workshop (including all that awesome psychological safety) which results in the transformation. The experience is why our approach is so much better than taking a pill or plugging into the Matrix.

But let’s save our words for the impact.

Let’s compellingly articulate the value we deliver.

Even when those words are hard.

Tim specializes in High-ROI workshops and off-sites that are lots of fun, but also ruthlessly focused on delivering high value. He's been facilitating workshops with senior executives for over 17 years, was part of the c-suite at one of the largest independent advertising agencies in the U.S. for a decade, began his career as a copywriter and creative director, and used to perform with an improv troupe in Los Angeles. So he brings a unique background of creativity, executive facilitation, and executive leadership experience to his clients and participants. He worked with Executive Programs with Hyper Island for many years, and also supports AJ&Smart with their corporate training business. As an in-demand public speaker, he’s been featured multiple times at the Cannes Lions, SXSW, TEDx and on many other global stages.

Tim Leake

This year we decided to focus the report on the topic of impact, precisely because it’s a territory where things are yet unclear. How can we assess the impact of facilitation? Should the idea even be on the table in such a relational field? And if not, how can we justify investments in hiring and training facilitators? We hope that discussing what is happening will help us see where the field needs to go next.

In this section, we examine why practitioners evaluate their sessions, which methods they use, and the barriers they face in doing so.

We’ll see how a majority of facilitators are evaluating participant satisfaction, relying on tools such as surveys at the end of sessions, and using this information mostly for their own improvement. While such reflective practices are fundamental to professional growth, they may no longer be sufficient to justify expenses for facilitation and training.

Fewer than 1 in 3 facilitators had agreed on measurable performance indicators with their clients. Overall, these findings indicate that facilitators could strengthen the relevance of their programs by defining clearer goals and integrating impact considerations into their process from the outset.

The top two indicators of success reported by facilitators are “participant satisfaction” (71.8%) and “engagement levels” (69.8%). Both of these have to do with measuring performance, rather than impact. They can say a lot about how a session is going, and give facilitators hints on how to improve their work. These reflective habits are well established in the field, and offer a solid foundation for developing more robust evaluation approaches.

On the other hand, only 33.1% of facilitators have an agreement with clients on what will constitute success. We will see throughout the report that there is room for improving what happens before and after sessions, expanding the definition of success beyond immediate participant experience.

When we approached the survey results, we expected to read that facilitators gave little attention to evaluation or impact. This turned out to be a misconception: only a small minority of respondents (3.7%) report doing no assessment at all. Instead, we see that most facilitators are evaluating their work, but primarily in terms of performance.

The most common practice is gathering end-of-session feedback from participants to refine one’s facilitation. 43.9% of respondents presumably keep those results mostly to themselves (or their team), with only 19.1% running some form of evaluation with the intention of proving impact to clients or stakeholders.

When asked a more granular question about assessment methods, the most popular answers were post-session follow-ups (71.2%) and facilitator debriefs (70.2%). Clearly reflection—whether with participants or within the facilitation team—is the primary mode of looking back and trying to figure out how things went.

A second tier of methods (30 to 40%) shows a moderate uptake of more formalised approaches: pre-session needs analysis, defining measurable objectives, and collecting data against defined objectives. These practices indicate a shift toward more structured evaluation frameworks, though these are not yet universally adopted.

Impact stories (31.4%) suggest an interest in narrative-based evaluation, connecting facilitation outcomes to compelling examples that help clients understand value (we’ll see more about this in the next section, Communicating Value).

Only a small minority (3.3%) report that impact assessment does not apply to their work, confirming that evaluation is becoming an expected part of professional facilitation practice.

If we add a breakdown by experience to this data, we can see that experienced facilitators are more likely to integrate follow-ups, debriefs and needs analysis. Beginners and intermediates show much lighter use of these methods. This suggests that rigorous evaluation is a learned practice, not yet embedded across the field. Practitioners may need greater support in developing these habits earlier.

Unsurprisingly, opportunities for the facilitator to check in on participants or follow-up after sessions diminish in time, with 47.6% of facilitators running their assessments immediately or within one week after a session (40.9%). This makes sense, but at the same time we know that to sustain actual change and check for progress on actions agreed upon at the end of a workshop, it would be more effective to check in later, and repeatedly.

These results open up another range of questions: can one-off sessions be effective in bringing about real change? What are the barriers to establishing longer-term working relationships with clients and teams? We’ll look into this in more detail in the question on barriers, below.

Regular follow-up appears achievable for many facilitators, but not universal. The drop from “after most sessions” (29%) to “occasionally” (19.3%) and “only for major engagements” (13.3%) hints at practical constraints such as time, access to participants, or client expectations.

Let’s look at what tools support facilitators in their evaluation work. These tend to be accessible, multi-purpose survey forms. Generally speaking, these are lightweight systems that enable quick feedback rather than comprehensive evaluation. Google Forms (48.4%), Mentimeter (29.9%) and Microsoft Forms (28.4%) were the most common choices. Of these, only Mentimeter is custom-made for interactivity (e.g. in-session use).

In that 21.3% of “Other” responses, phone calls and email feedback were mentioned a dozen times, while most remaining entries are individual tools or custom processes mentioned only once. This reflects a wider challenge: many facilitators want to understand their impact but lack tried-and-tested methods or common standards. Developing more coherent evaluation habits may be an important next step for the profession.

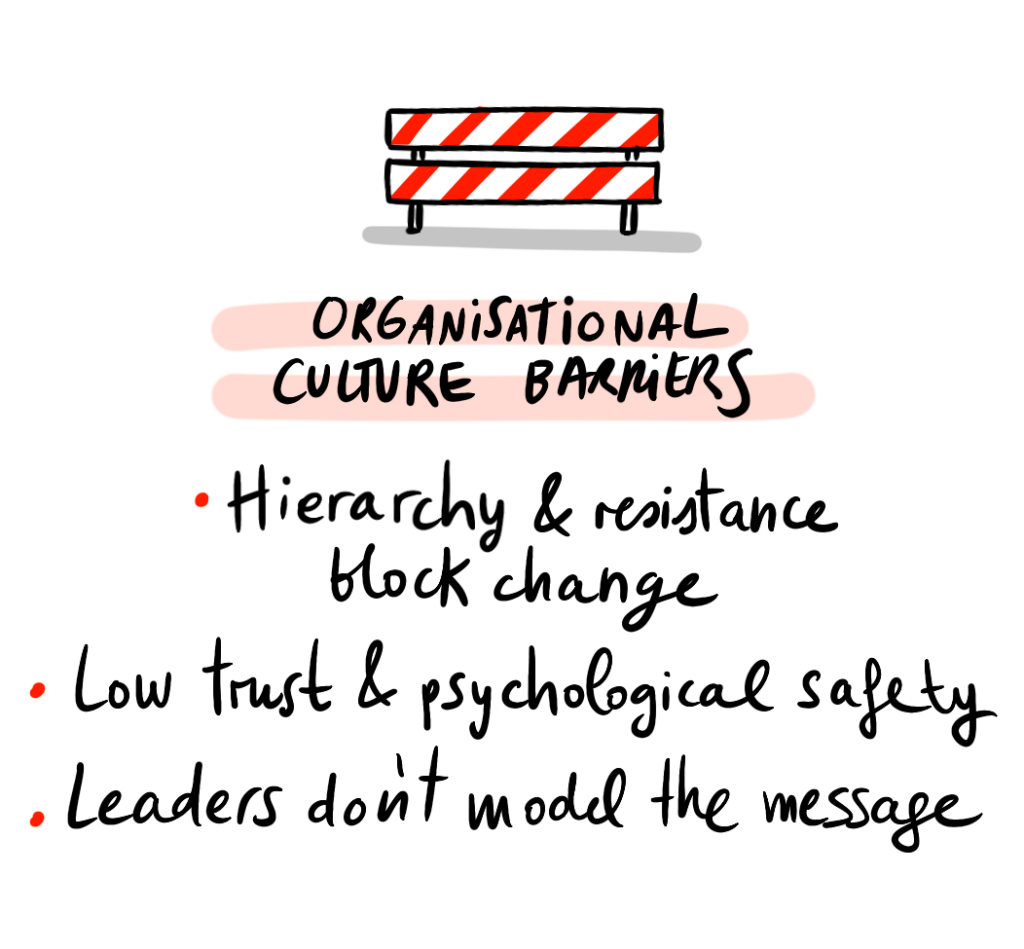

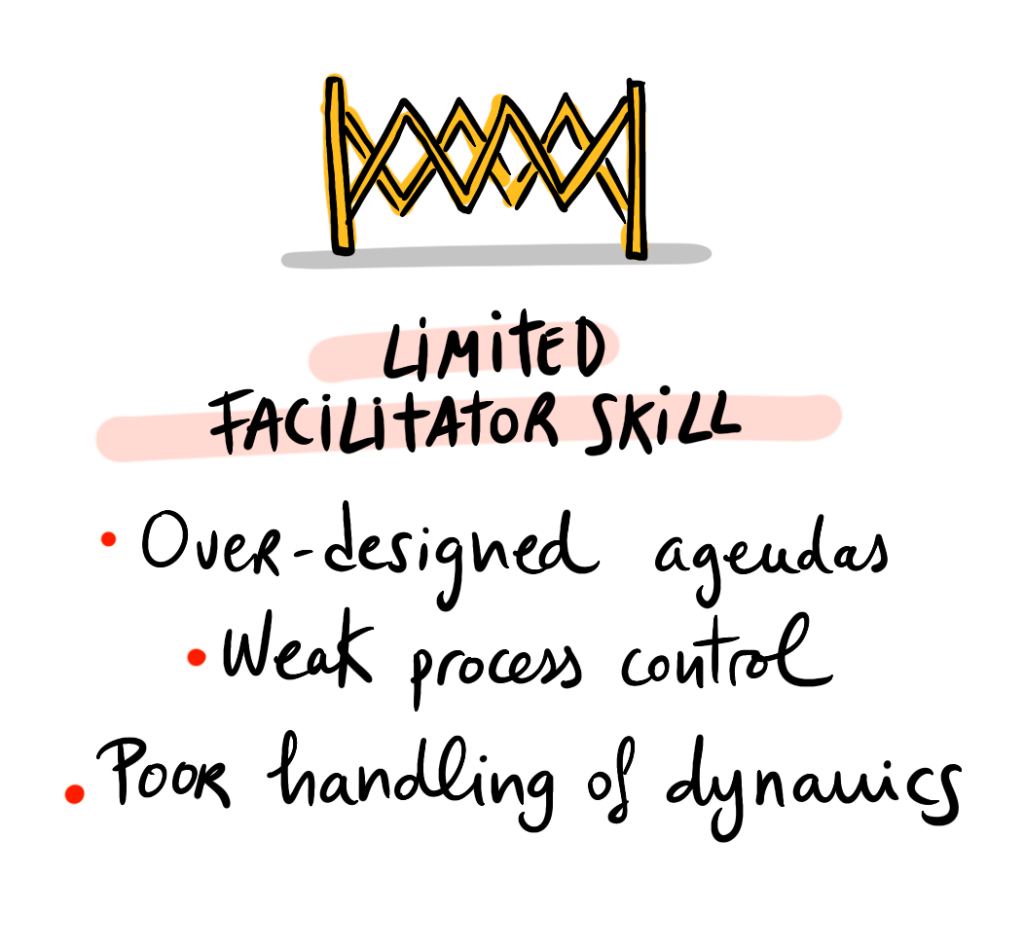

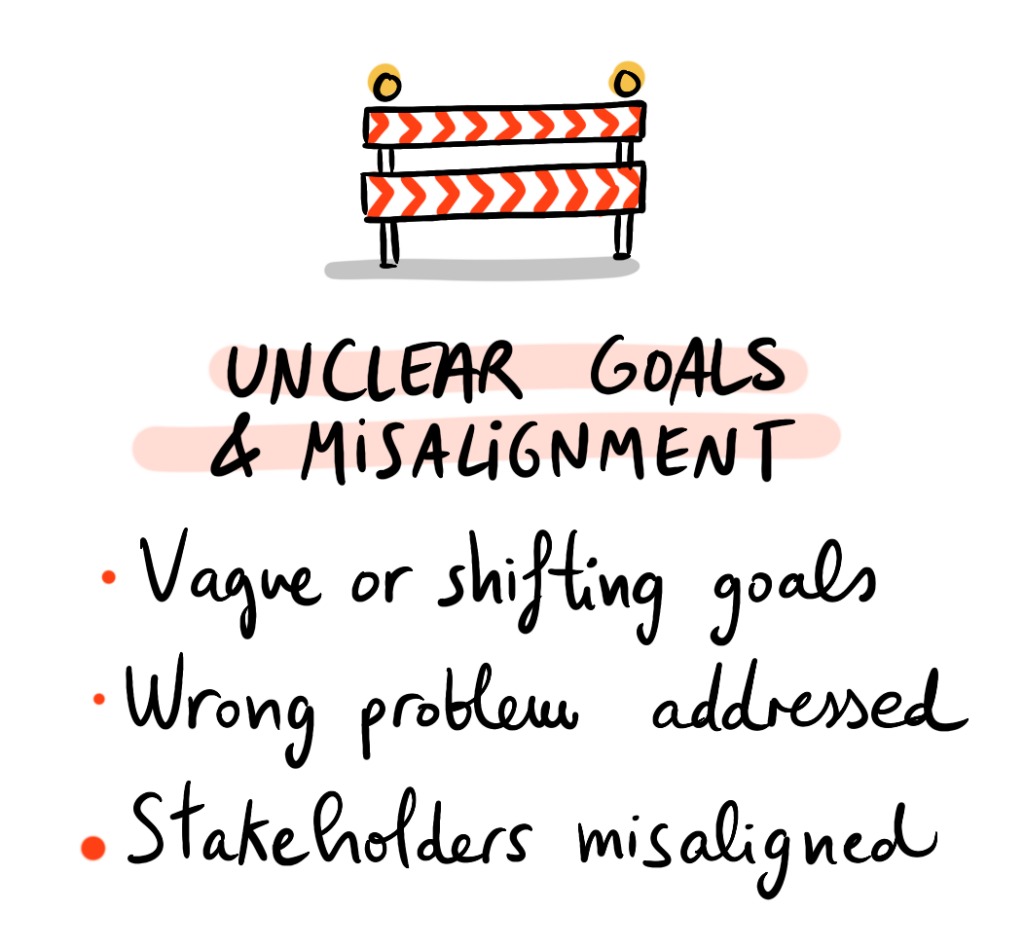

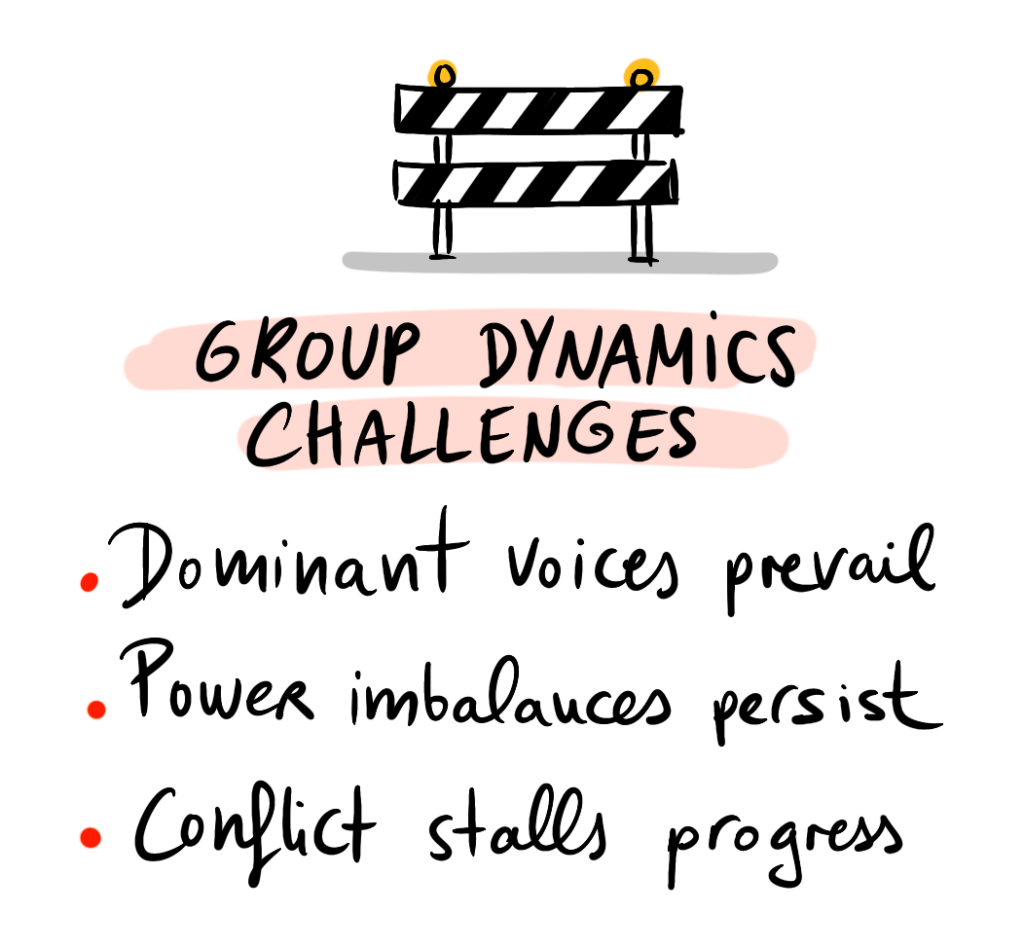

Most challenges named by respondents relate to structural and relational issues rather than tools. “Other” responses highlight long time horizons for behaviour change, unclear client goals, and concerns about the reliability of participant feedback.

Many of the most common challenges are relational, not technical.

The top barriers reported (lack of client feedback, unclear goals, difficulty isolating the effect of facilitation) stem from collaboration and alignment rather than from the absence of tools. This points to a wider challenge: without clearer goals, follow-up or shared measurement practices, it becomes harder to explain facilitation’s value in complex environments.

Improving impact assessment requires, at its core, changes in how facilitators frame their work. Considerations around impact should come at every stage of the process, not as a last-minute add-on.

Streamline your end-to-end planning process, from brief and agenda to post-session feedback.

Capture client notes, participant feedback and supporting information in one place. Simplify your collaborative workflow and demonstrate impact with SessionLab.

One of the clearest themes emerging from the data is that the learning and development community is deeply committed to ‘impact’. Yet the conversations within the field reveal that the word impact is doing a lot of heavy lifting. As Melanie notes, practitioners often “focus mainly on satisfaction,” even though “there is no correlation between satisfaction and application (Alliger & Janak, 1989).” The data reinforces this longstanding tension: we are using one word to describe several fundamentally different outcomes.

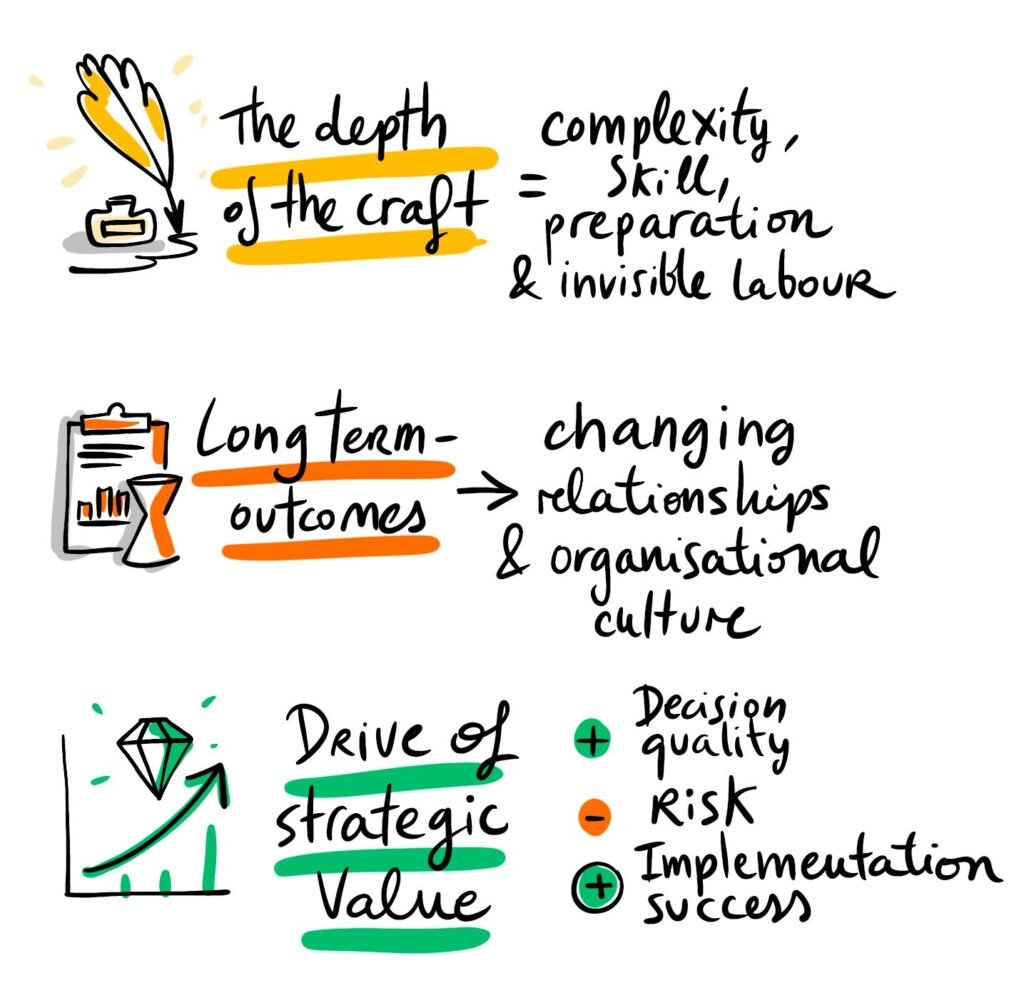

From our perspective, ‘impact’ is currently a shorthand for three distinct ideas:

Each of these is important. Each deserves to be understood. But they are not interchangeable. And when they blur, it becomes difficult for organizations to design effective evaluation strategies. As Chris puts it, “We need to define what we’re talking about when we say ‘impact’, because much of the existing data focuses on how successfully the facilitator engages participants in the room versus the change that’s created for the organization.”

Impact Must Be Defined Upfront

One shared observation is that many challenges highlighted in the report stem from evaluation beginning too late. Teams often measure only what is easy—typically so-called Level 1 reactions—rather than what is meaningful. Melanie sums up the risk: “Meaningful evaluation is only possible when you know where you are going. If you don’t know where you are headed, how can you measure if you actually reached your desired destination?” If the desired business outcomes are not defined during contracting, practitioners are left trying to isolate impact retroactively: a task that is both unreliable and unnecessarily difficult.

Impact measurement becomes dramatically more feasible when expectations are explicit. Clarifying the Return On Expectations (ROE) gives both the facilitator and the client a shared direction, enabling more targeted evaluation and more actionable insights. Some questions that may help in clarifying the desired ROE:

How did the idea of the course / workshop come about?

Which strategically relevant topics and numbers could/should the training/workshop/session influence positively/make a positive contribution to?

Imagine the program achieves its goals. How are participants acting differently afterwards? How do you imagine that will impact the business?

A Multi-Stage, Multi-Method Approach

The report’s findings show that most respondents’ evaluation happens immediately after a session. While these early data points matter — relevance, confidence, and intent-to-apply are predictive indicators — they do not yet reflect behavior change. “All that I can say after a few days,” Melanie explains, “is whether I liked it and whether I have a plan to apply, but there’s no proof yet.” Actual impact unfolds across time.

A stronger approach blends multiple sources, multiple methods, and multiple time points. Qualitative stories can complement quantitative measures; observation and follow-ups can validate early indicators; manager input can contextualize progress and barriers. As Chris emphasizes, evaluation data should serve three purposes: “Yes, validate impact — but also use it to course correct, and use it to inform what comes next.”

This ongoing rhythm shifts evaluation from a one-time audit to a continuous feedback system capable of supporting real change.

Recommendations for Strengthening Evaluation and Impact

Based on our combined experience and what the report surfaces, we offer several practical recommendations for practitioners seeking to deepen their impact evaluation:

A Shared Opportunity

The field’s commitment to impact is clear. What the data highlights — and what our experience reinforces — is the need for clearer definitions, earlier alignment, and more continuous evaluation rhythms. None of this replaces existing practice; rather, it enhances it. By distinguishing between types of impact and measuring what matters at the moments that matter, practitioners can demonstrate value more confidently and create stronger outcomes for learners and organizations alike.

Chris founded Actionable.co in 2008 to help leadership and change consultants prove the behavior change impact of their corporate learning programs. Since then, Chris – and his team at Actionable – have supported the deployment of over 7000+ programs leveraging the Undeniable Impact framework for driving change.

In addition to being a regular speaker for both public and private events, Chris has penned over 150 articles for dozens of publications, been quoted in The National Post, Toronto Star and Globe & Mail and hosted 90+ thought leader interviews for the iTunes #2 ranked business podcast, The 21st Century Workplace.

Melanie combines her entrepreneurial spirit with 18+ years of experience in L&D to help build memorable & results-based learning experiences. In her roles as CEO at the Institute for Transfer Effectiveness and Founder of Going Beyond Training,

Melanie is passionate about making transfer happen. She applies strong business acumen, rich practical experience across cultures & a deep understanding of what makes learning stick to support her clients in being more strategic in their L&D initiatives.

Melanie Martinelli

From the responses shared within measures of success, reasons to evaluate, and assessment methods, there is a clear desire and excitement for evaluation within facilitation. The majority of respondents undoubtedly have identified the need for knowledge and satisfaction assessment. However, this data stops merely at the facilitator and doesn’t necessarily translate into knowledge exchange. This is such a missed opportunity!

How can practitioners then bridge that connection between facilitating content and real-world applications of lessons learned? Connect the dots from the purpose and objectives of facilitation support to the client’s needs and desired outputs/outcomes. This can be done by implementing learning evaluation frameworks such as the Kirkpatrick Evaluation model, Kaufman’s Five Levels, and the CIPP (Context, Input, Process, and Product) Model, which incorporate the co-creation of learning questions and objectives at the design stage rather than simply utilizing post-session evaluations as a metric of success.

It may seem burdensome or even intimidating to change a tried-and-true method that has already been operating well for practitioners. However, these tweaks and adjustments will “level up” the facilitation approach and allow for even more engaging and meaningful sessions.

How can facilitators then make these tweaks? When possible, collaborate with your client and target audience to think with the end in mind. This increases buy-in from the client and participants, assisting in an even more robust methodology. In addition, solidify the learning objectives, learning questions, and evaluation framework before implementing your facilitation.

Through collaboration and meaningful design, evaluation can become more than just a single event but a woven element into the practitioner’s toolbelt. It’s all about helping show the logic of your thinking. When utilizing all the tools in the facilitator’s toolbelt, such as pulse check surveys and pre-/post-evaluations through Google Forms or Menti, virtual collaboration boards like Miro for qualitative feedback, or live capturing world cafe post-it reactions, there can be a rich amount of data to answer the learning questions and meet learning objectives. These small tweaks allow for sustainable facilitation and lead to understanding the (often elusive) impact.

Christine E. Thomas, MPH is a Social Impact Evaluation and Strategy Consultant and the Founder + Principal Consultant of Limitless Creativity, LLC, a strategic advisory firm supporting mission-driven organizations. With over a decade of experience in evaluation, impact assessment, and strategic learning, her work focuses on helping organizations and teams understand how to make data useful, meaningful, and integrated into the big picture.

Christine Thomas

In this section, we look at the topic of increasing facilitation’s impact.

To do this, we asked some open questions about what creates impact in facilitation, and what barriers and challenges stand in the way.

The story facilitators tell goes like this: the practices that generate meaningful outcomes are relational and hard to quantify. As for the barriers that limit impact, they tend to be structural and outside the facilitator’s control.

This fits the picture painted above: facilitators feel they have control on what they do during sessions; they collect feedback, and reflect on it in order to grow and improve. What happens after or in-between sessions, on the other hand, seems to be a bit of a black box.

While steering clear of the impulse to quantify everything, we’ll still challenge this view, as there is much more facilitators can do to demonstrate impact and increase uptake (of decisions taken) and learning retention. In this, experienced practitioners are leading the way.

We also check in about favorite learning resources, and what frameworks expert facilitators have been borrowing to learn more about evaluating impact.

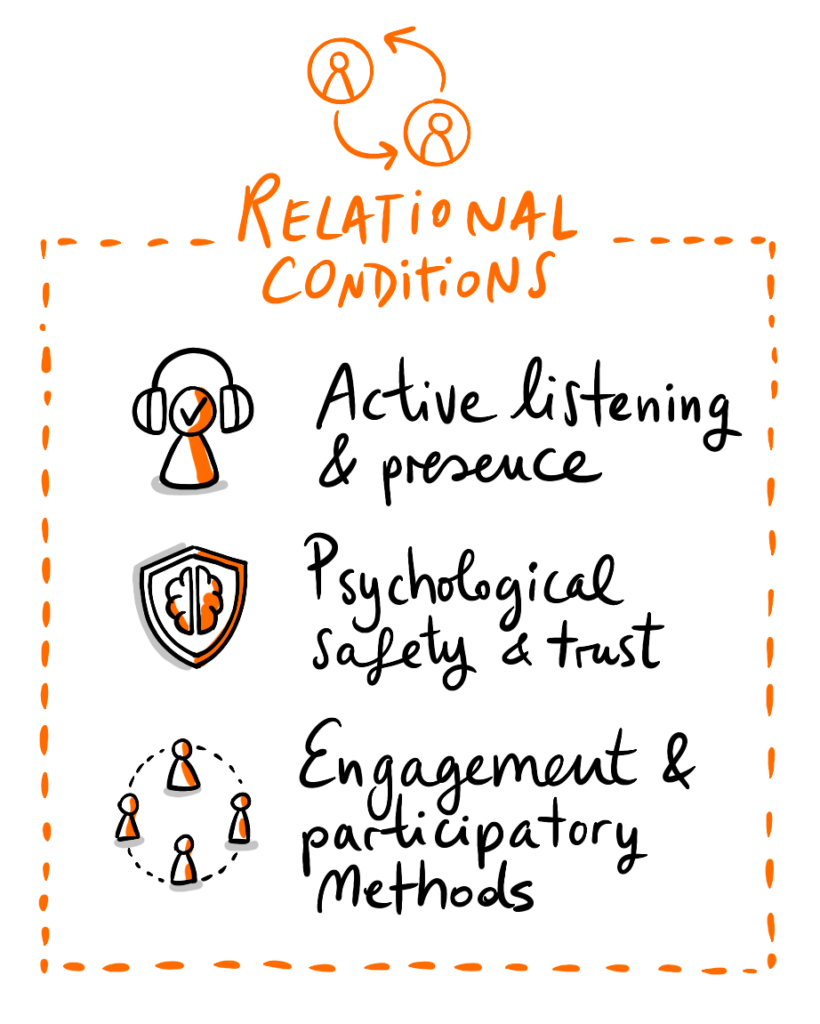

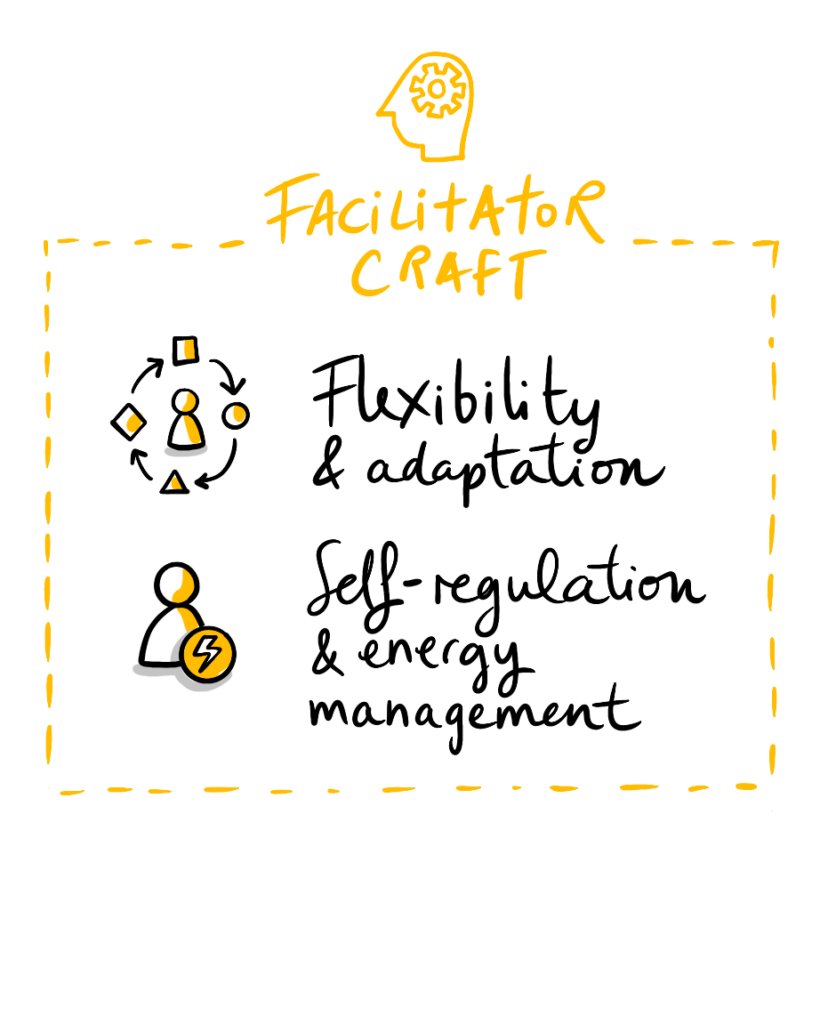

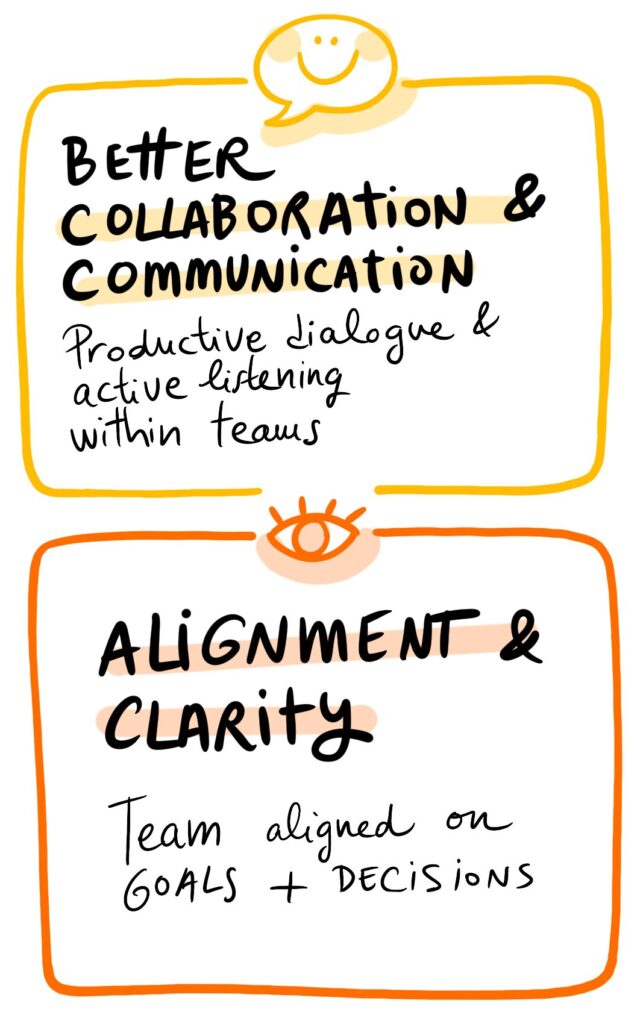

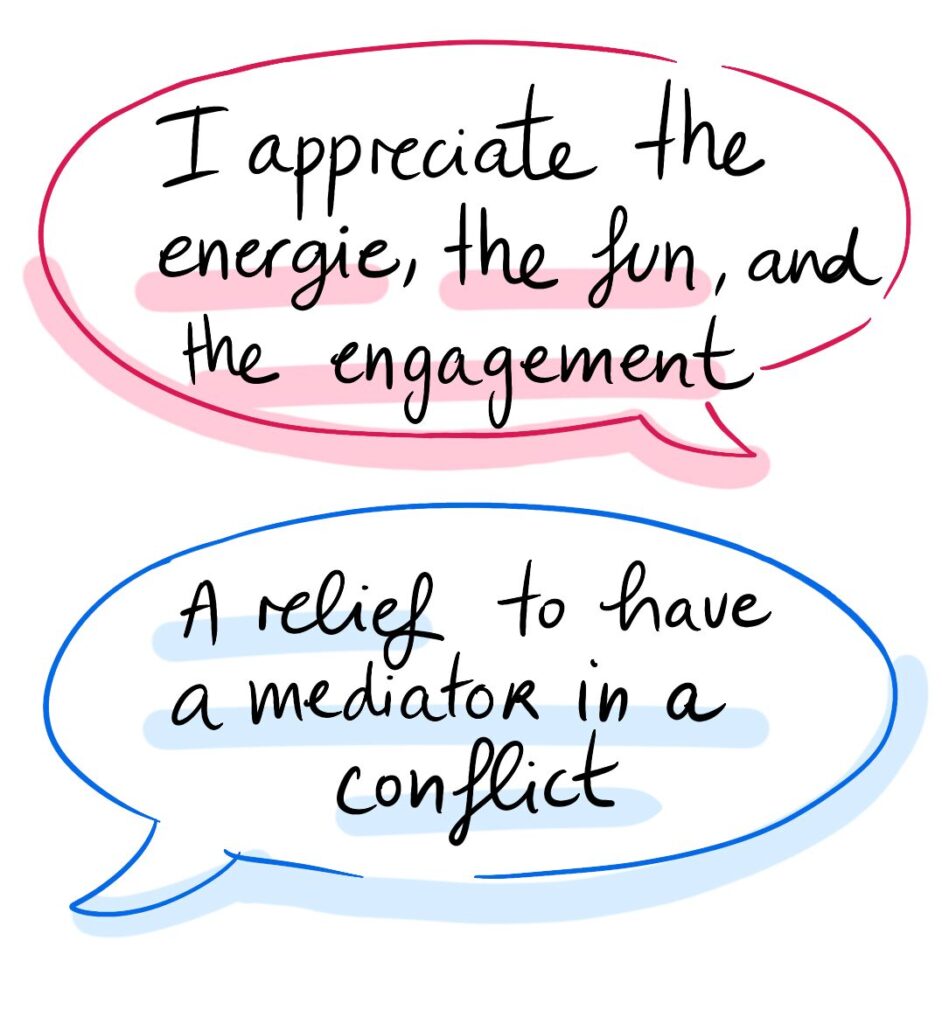

In their answers to an open question about what facilitation practices are most impactful, summarized above, facilitators consistently point to practices that are difficult or impossible to quantify: presence, trust, listening, safety, clarity, attunement. Even when asked directly about “impact”, people describe conditions, behaviours, and intangibles rather than metrics.

This contrast is revealing:

Both are true.

The most impactful facilitation moments are often relational, not measurable

When facilitators say that “deep listening”, “presence”, or “safety” have the strongest effect on outcomes, they are describing micro-behaviours that change human interaction in ways that resist quantification.

You can measure outputs — decisions made, commitments defined, satisfaction scores — but not the catalytic moment when people felt safe enough to tell the truth.

A more nuanced view emerges:

…and facilitators increasingly need to do this to demonstrate value, especially in corporate environments.

…and facilitators instinctively name these as their greatest contributors to impact.

… making the invisible visible.

Across the data, facilitators describe a clear pattern: impact is shaped by the interplay between what happens in a session and what happens afterwards, when larger organizational culture comes into play.

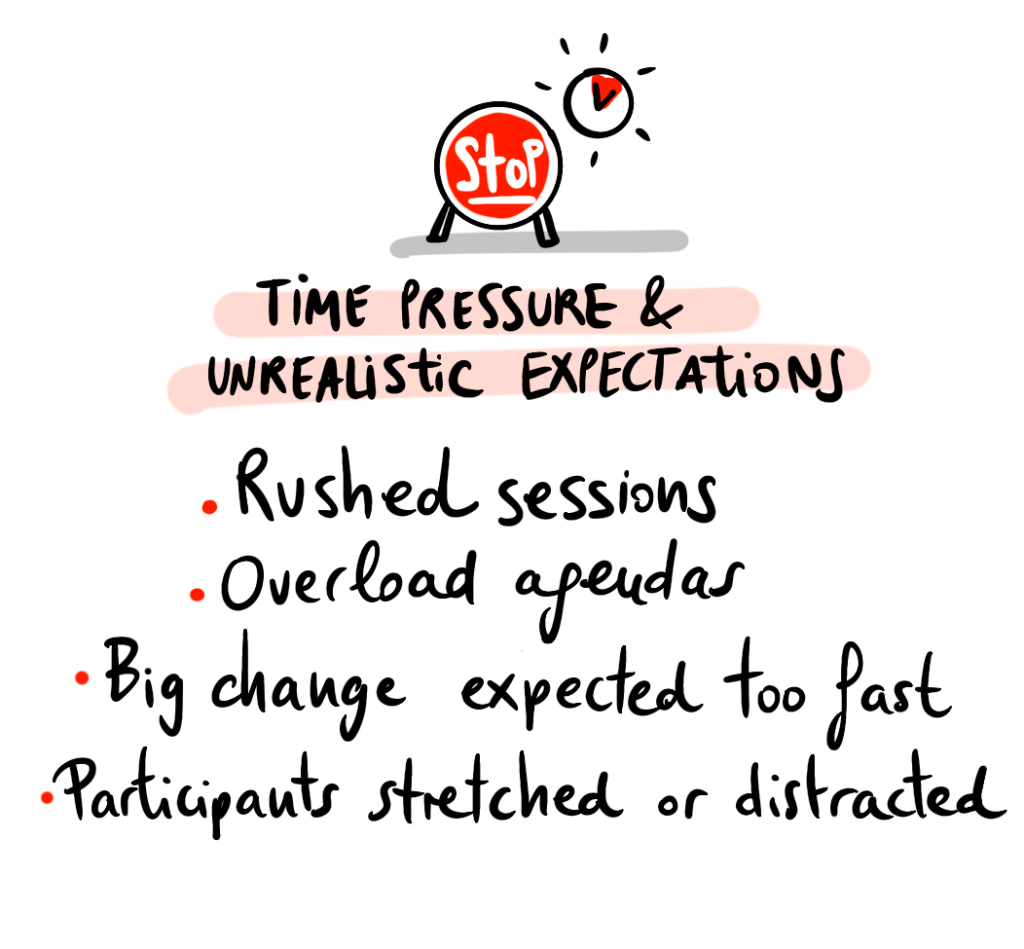

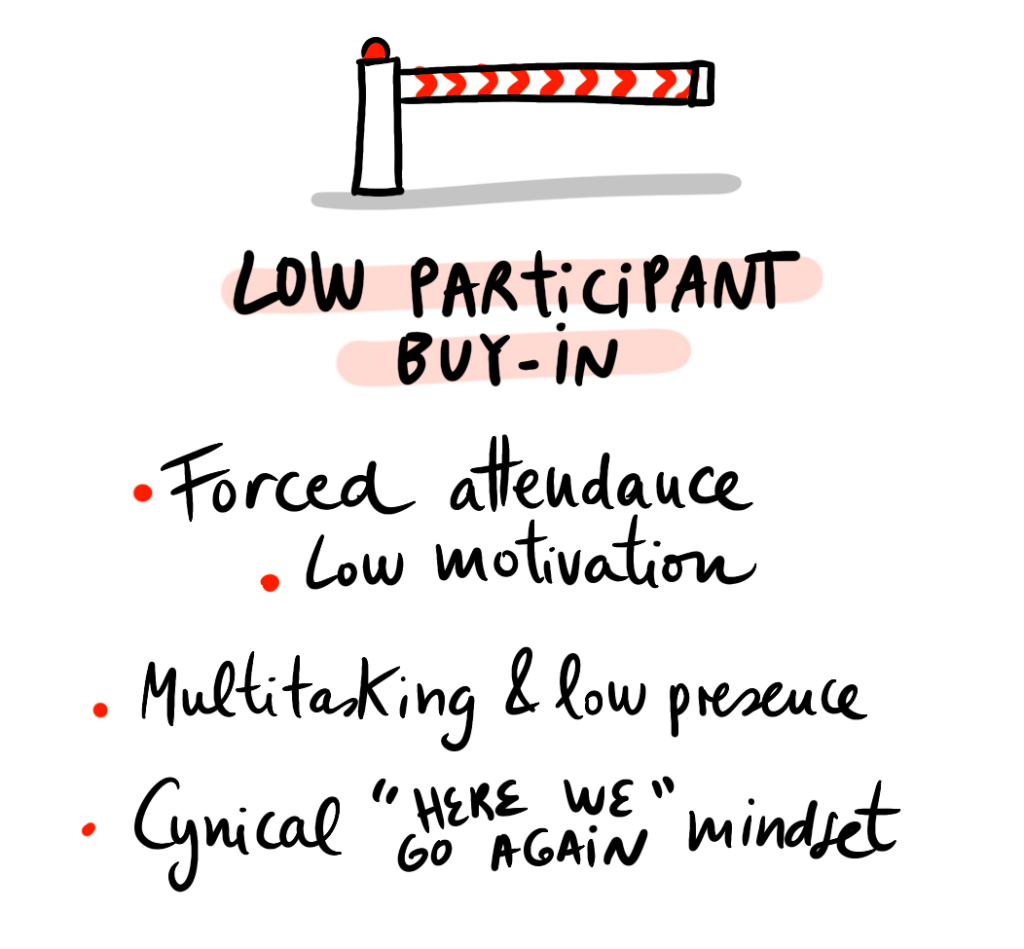

Lack of follow-through, unclear goals, disengaged participants, and working cultures that make honest collaboration difficult are the strongest barriers detected. The problem is, it’s a lot easier for facilitators to influence dynamics within sessions than before or after.

This suggests that improving facilitation’s impact is a shared responsibility. Impact ultimately depends on whether leaders and teams create the right conditions for actions to “stick”.

So how can facilitators influence those conditions? What can they do to contribute to creating organization-wide cultures of facilitation?

The pathway forward lies not in grand redesigns but in small, reinforcing practices that strengthen clarity, follow-through, and shared ownership. Ultimately, the most impactful facilitators are those who focus a lot of attention on conversations with key decision-makers and clients before and after sessions and workshops.

Lack of an overall plan with allocated resources to implement actions that may be established from facilitation.

Building in the time for facilitation rather than cramming sessions with no room for participants to contribute and engage with one another.

People feel like they don't have time for something to be facilitated because they need to get the work done. They don't realize that they're work would be better if given the time.

After the session, participants go back to a work environment and systems which weren't designed to support the changes explored during the session.

Support for the goal of the session from various levels of the company or organizational hierarchy is important to the success of facilitation.

Performative participation. People show up, say the “right” things, and leave unchanged. They offer polite engagement, but won't risk being authentic.

The biggest barrier isn’t resistance, it’ss compliance. Real impact requires discomfort, honesty, and letting go of control.

Unrealistic expectations; often clients expect everything to be solved in just a couple of hours when the reality is, multiple sessions may be necessary.

There’s a dirty little secret that’s gone unspoken for far too long in the facilitation, training, and L&D space, and I am thrilled this report is finally calling it out. The vast majority of sessions result in inspiration but not necessarily transformation in the form of sustained behavior change.

The hard truth is that even the best-designed and facilitated sessions fail to create lasting impact if participants lack opportunities or resources to practice and apply what they’ve learned on the job. I know the feeling of disbelief (and a bit of despair) when I first learned that the workplace environment has the greatest influence over behavior change. Back in the 1930s, Kurt Lewin captured this in his equation: Behavior (B) is a function of the Person (P) and their Environment (E).

The good news is we are not here to play the blame game. No one person or group is solely responsible. As the report mentions, the impact of our sessions is a shared responsibility—between the facilitators, learners, and the organization’s stakeholders. It is our job to be aware of and articulate these limitations to our participants and stakeholders in order to maximize the impact we can have.

So how can we truly make a difference when we have limited influence over the workplace environment participants return to after sessions?

My answer: Co-creation!

Just as we co-create session designs for better results, we need to co-create the impact. Not only with our participants, but even more importantly, with the organization´s leaders and decision makers.

For the past 2 years, my colleagues, Maria Niederwieser and Craig Tindall, and I have been diving into how to create conditions for change, measure what matters, and act on evidence to maximize learning impact. While most of us understand that measuring impact is important, far fewer know simple, science-backed strategies to make it actionable. Check out Oh My Impact! for more robust resources there!

Below are some of my favorite practices for strengthening co-ownership of impact before, during, and after sessions in a well-known facilitator format: BINGO!

As you play, see which practices you’re already doing and which you might lean into more intentionally to boost the impact of your sessions throughout the year.

BEFORE SESSIONS

Set expectations early (and honestly)

You talk openly about the limits of one-off sessions, ask clients if they desire inspiration or transformation, and position follow-up interventions as a core part of the learning journey to ensure accountability (not as a later-added upsell).

Design for real work application

You anchor the learning in participants’ actual projects, workflows, and upcoming deadlines. Sessions are scheduled to align with real work opportunities so that practice happens inside the job, not on top of it.

Secure visible leadership buy-in

Leveraging “authority bias”, you involve senior leaders early by asking them to open the program, send an email, or record a video for participants to grasp why this work truly matters to the team and organization.

DURING SESSIONS

Help participants personalize their “why”

Tapping into intrinsic motivation, you create space for self-reflection on why the session topic matters to them and how the learning connects to their values or personal goals – even when the session is mandatory to attend.

Design for active and embodied practice

Sessions are not only discussion-based but instead designed to help participants actively practice what we’re there to build, using real work scenarios and case studies, embodied experiences with live feedback loops, project-based work, etc.

Lock in action and accountability

You ensure participants leave with a clear, actionable plan, which might include micro-steps to the goal, obstacles that can get in the way, risk-management strategies to counter-act them, and an accountability partner system to boost follow-through.

AFTER SESSIONS

Follow up to reinforce, not just recap

Participants receive follow-up resources, tools, email reminders, and videos in a scheduled cadence after the sessions to encourage practice and continuous application of skills once real life resumes.

Help leaders embed learning into workflows

You host an audit with team leaders and stakeholders to pinpoint continuous opportunities to apply the competencies in upcoming meetings, rituals, projects, and communities of practice.

Measure and amplify impact over time

You collect quantitative and qualitative data several months after the sessions to capture longer-term impact in participants’ own words, and help leaders share that progress visibly across the organization.

How many of these do you already do?

Romy is a Chief Learning Officer, Learning Experience Designer, and Facilitator on a mission to humanize workplaces and learning spaces. She specializes in designing and delivering transformative learning experiences that integrate psychological safety, experiential learning, neuroscience, and behavior change.

A Fulbright Scholar and former Peace Corps Volunteer, Romy brings a global perspective and over 15 years of experience spanning 90 countries across 5 continents. From Fortune 500 companies to governments to UN agencies to Formula 1, Romy helps individuals and teams unlock their potential and accelerate high performance. In 2024, Romy was honored as a LinkedIn Top Voice for her thought leadership in experiential learning and workplace culture.

Romy Alexandra

The responses collected overall on the topic of impact paint the picture of a sector that has yet to develop a systematic approach to assessing its own merits. So let’s look at where practitioners might want to go to learn more, and take those next steps.

When asked about learning resources, facilitators pointed to social and peer learning: peer discussions and communities are the ideal situations to learn from one another. Facilitator communities have multiplied in the past few years, so if you are not part of one yet, consider joining. And for all those already involved in peer-to-peer learning, we hope this report encourages you to host conversations around evaluation, assessment, and sharing stories of impact.

As for more structured approaches to learning, we asked for resource recommendations on impact but the responses we got were more around favorite resources for learning about facilitation. Here are recommended top 5 podcasts, newsletters, and books:

Podcasts

Top newsletters

Top 5 Most Recommended Facilitation Books

Across all responses, very few facilitators cite resources specifically designed for facilitation impact measurement. Some mentioned the Kirkpatrick Model of training evaluation, or advised looking into Theory of Change resources and Monitoring and evaluation literature. In terms of books, a repeated mention was “Measure What Matters” by John Doerr.

Respondents mentioned using materials from management, behaviour science, learning and development, and education, fields which provide models for defining or measuring behaviour change.

Impact evaluation in facilitation is underdeveloped as a speciality: practitioners are piecing together approaches from adjacent fields. There is an opportunity to develop tools, frameworks and practices adapted specifically to the reality of facilitation.

As a final note on the topic of continuous learning, being aware that co-facilitation is a key learning pathway, we asked a specific question about what makes co-facilitation more powerful.

Co-facilitation is one of the most common ways to learn from and with peers. How do facilitators formalize such learning? It’s fun to notice that about half have unstructured chats and conversations, and the other half has some kind of structured format for reflection.

When comparing experience levels, facilitators’ improvement practices diverge in clear ways. Beginners rely mostly on unstructured conversations (≈72% of beginners selected this) and are far more likely to say co-facilitation practices don’t apply to their work (≈28%).

Intermediate facilitators engage the most in team-based learning. They are the group most likely to develop shared templates or materials (≈58%) and to participate in team trainings or skill-shares (≈51%).

Experienced facilitators favour more deliberate, systematic approaches: they are significantly more likely to use structured retrospectives (≈44% versus ≈29% of intermediates and ≈18% of beginners) and to review data together (≈23%, compared to under 10% for beginners). They also stand out for consistently refining and reusing past agendas (≈62%). These patterns suggest a developmental arc: facilitators begin with informal reflection, move into collaborative learning as their practice matures, and ultimately adopt intentional, data-informed processes to improve their craft over time.

Four eyes see more than two. Especially in facilitation.

Most facilitators remember the session that almost worked. The design was solid, the energy was decent, yet something felt slightly off. Now imagine having someone next to you who noticed exactly what that something was, and helped you adjust in real time. That’s the quiet superpower of co-facilitation.

As with many things in life, we simply do better together. We know this from learning: how much more powerful it is to attend a workshop or conference with someone else. Someone to reflect with, challenge assumptions and, most importantly, make a plan with when you’re back at work. How will we integrate what we learned into our reality? Co-facilitation brings that same social accountability directly into the facilitation practice itself.

Personally, I’ve learned the most when facilitating with someone else. It becomes immediately clear how differently we see the same room. One of us might take the lead, while the other stays slightly in the background, sensing energy, tracking participation, and using breaks to reflect together. Where is the group right now? What does that mean for what comes next? Other times we divide exercises, sharing the cognitive and emotional load. Because holding space, staying present, and reading a group in real time takes a lot of energy (more than we often admit).

The data backs this up. Early-career facilitators tend to reflect informally and often alone, while more experienced facilitators increasingly rely on structured reflection, shared materials, and deliberate improvement practices. Co-facilitation seems to be a bridge in that journey — moving us from “How do I think it went?” to “What are we seeing together?”

A powerful but often missed opportunity is the debrief. When you co-facilitate, make space for a formal reflective conversation after the session, not just a quick “That went well!” Using a simple After Action Review can go a long way:

Always start with purpose. That’s what you evaluate yourself against—not perfection.

Perhaps the most underrated benefit of co-facilitation is self-compassion. Like leadership, facilitation is a practice where you always succeed with something—and never with everything. And that’s enough. Learning together helps us normalize that truth, accelerate our growth, and ultimately increase the impact we create for others.

So ask yourself:

Who could you invite to facilitate with you next time?

How might shared reflection increasing the impact?

And what would become possible if you stopped learning alone?

Anna Gullstrand is Chief People & Culture Officer at Mentimeter and an experienced facilitator, leadership educator, and author of Facilitate!, Sweden’s HR Book of the Year 2020.

Mentimeter, your Everyday Engagement Tool, is a 400-employee SaaS company with offices in Stockholm, Sydney and Toronto, widely used by educators, facilitators, and leaders to improve their practice, create business impact and contribute to a world where every voice is heard.

Anna Gullstrand

In the previous sections, we’ve looked at how and why facilitators assess their impact, and on what makes this easier or harder.

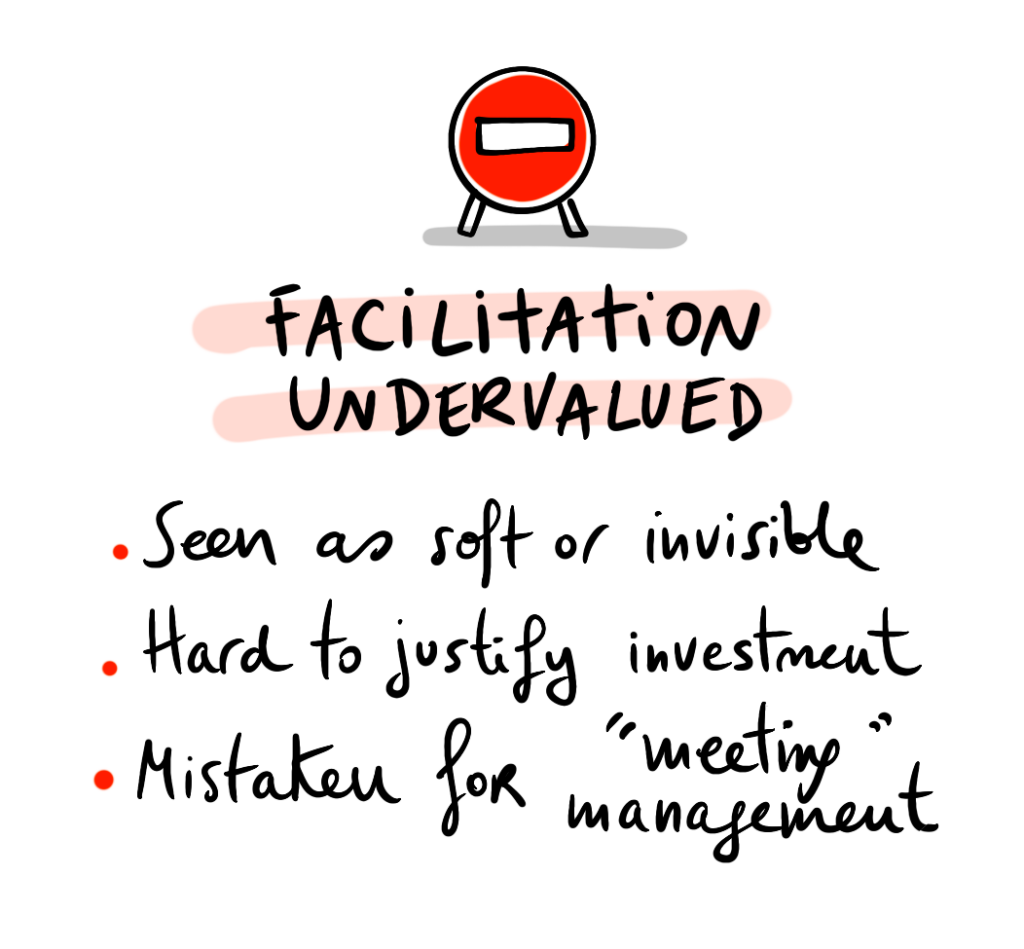

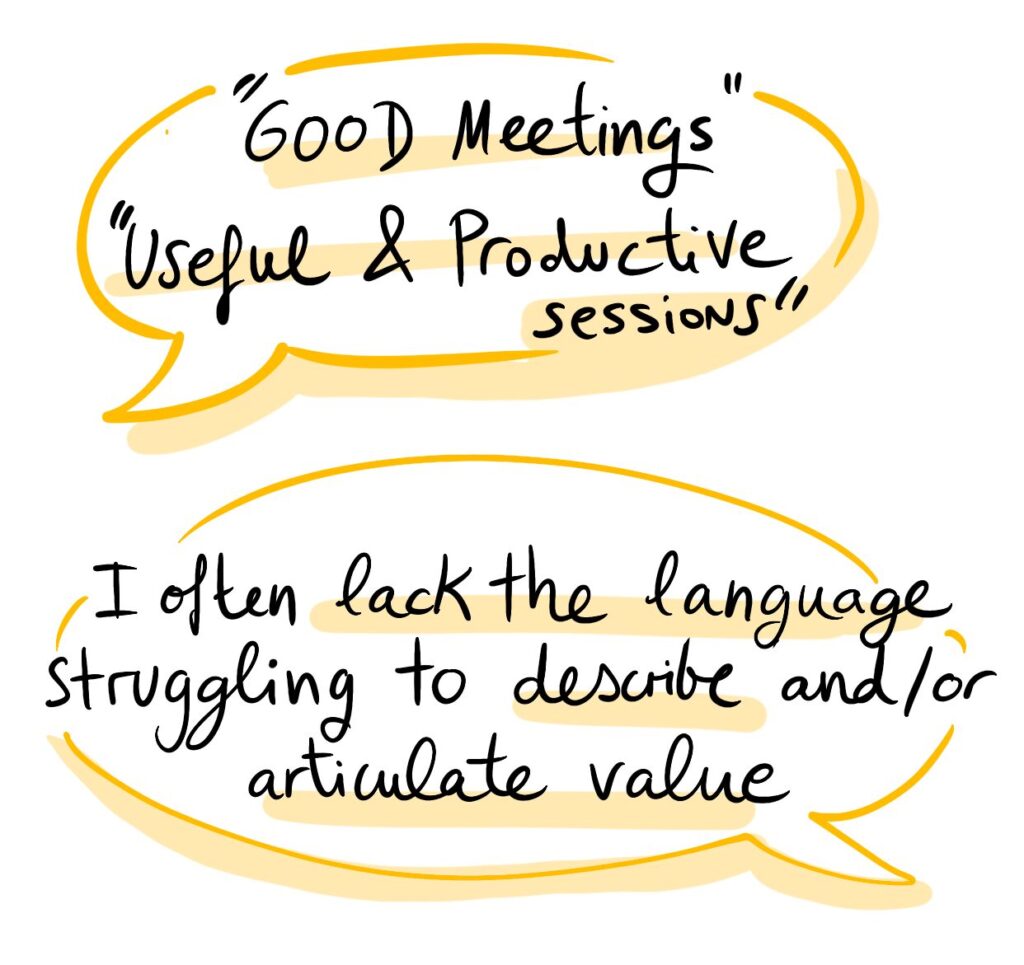

In this next part, we go deeper into the topic of how to talk about facilitation, it’s impact and it’s value. Practitioners and their clients often describe the impact of facilitation in vastly different ways. And the value of facilitation might just get lost in translation.

Learning to describe facilitation’s impact in meaningful and accessible ways might just be the most impactful thing the industry can do.

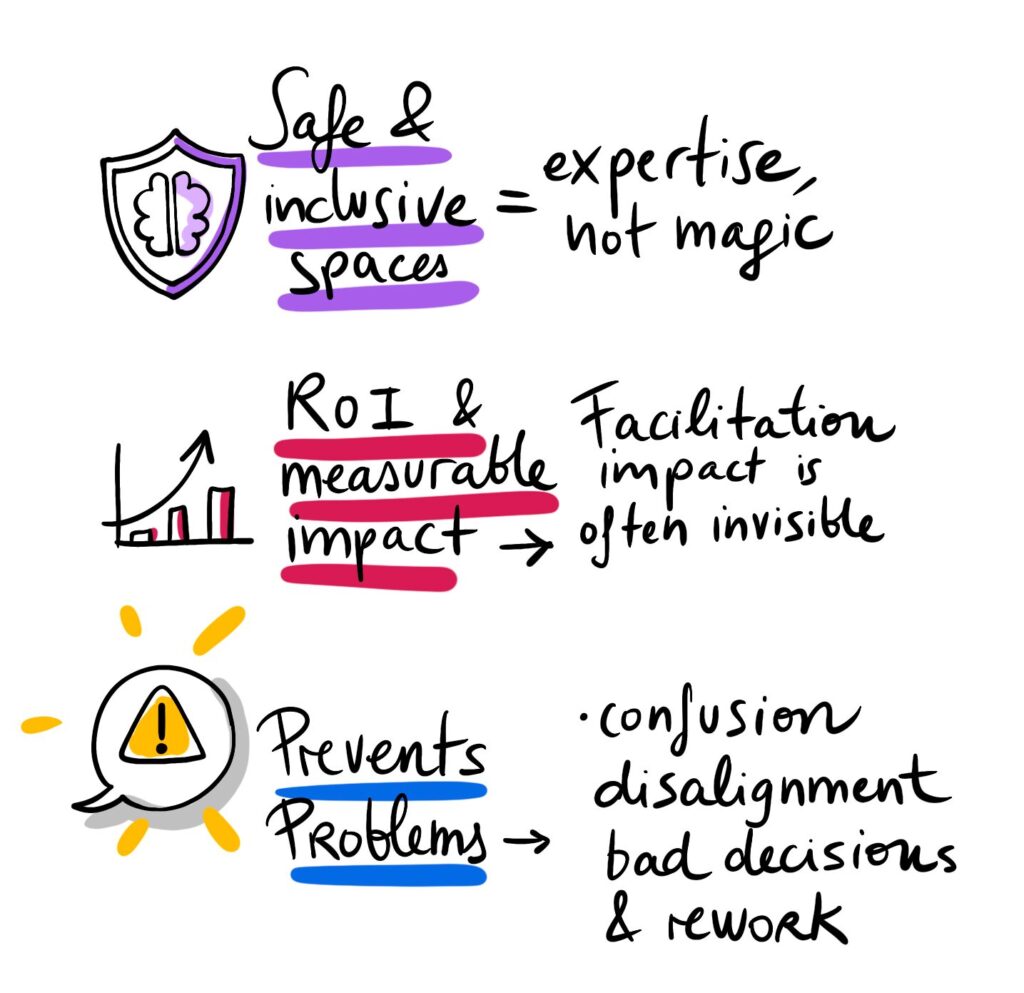

When 51.4% of facilitators rely primarily on word of mouth or informal sharing, and 39.3% communicate impact only inside their organisation, it means the value of facilitation rarely becomes visible beyond the immediate circle of people who already believe in it.

In other words:

the impact is happening, but it doesn’t travel.

This creates a structural problem for the field:

With only 17% publishing blog articles, 15.1% doing external reports and 4.5% writing research or books, the visible footprint of facilitation remains tiny relative to the scale of work being done.

This is one of the key conclusions emerging across the dataset:

facilitation may well be very impactful, but the field is under-communicating its value.

As mentioned in the brilliantly honest quote by a respondent (all information in the survey is anonymous, but you know who you are: thank you):

– How do you describe the value of facilitation?

– I don’t. I probably should, but I don’t.

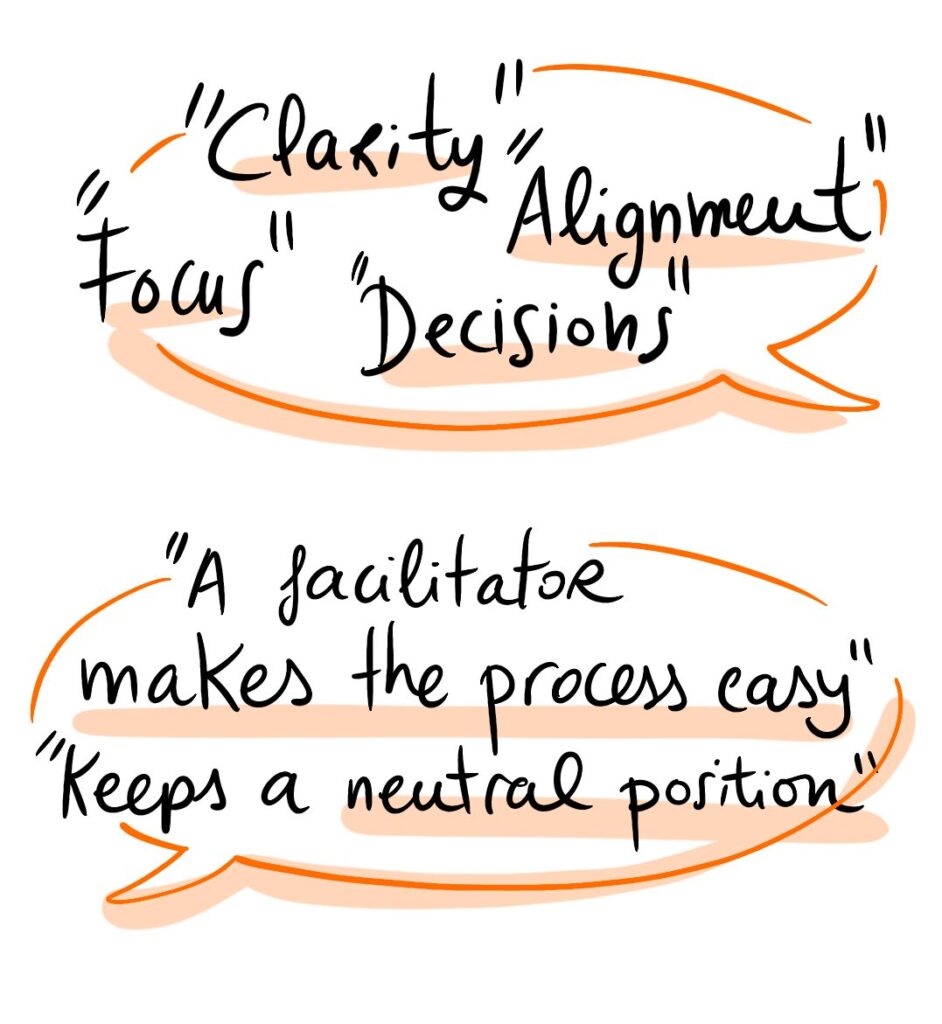

The top four outcomes sit relatively close together, and nothing dominates to an extreme degree — which suggests facilitators frame their value in multiple, overlapping ways rather than relying on a single headline outcome.

That said, facilitators are most likely to promote outcomes that describe shifts in behaviour and collaboration (40%–63%). Business impact is present in the background (KPIs, 26%), pointing to a translation challenge: connecting relational change to organisational results in language decision-makers recognise.

I believe that facilitation skills are leadership skills for our modern era. If anyone is bringing people together -- team meetings, whole company gatherings, community groups, even 1:1's... you need to learn how to facilitate to be an effective leader.

The value of facilitation is about creating the conditions for groups to do their best work together.

I don't.

I probably should, but I don't.

A productive move away from soul destroying meetings.

It's the WD-40 of work processes -- it loosens things up so people can shift their POVs and engage in discovery.

"get 6 months of work

done in 3 days"

Este un catalizator: transformă un grup de oameni într-o comunitate care înțelege mai bine direcția și modul în care poate colabora.

(It is a catalyst: it transforms a group of people into a community that better understands the direction and how it can work together.)

Honestly, most clients don't naturally think in terms of "facilitation." They usually just describe what they need in much more practical terms like "we need to get unstuck on this decision," "we have to figure out our strategy for next year," or "there are tensions in the team we need to address." The word "facilitation" sounds too abstract for many. They care about the result, not the method.

Clients often say that, as a result of facilitation, there is more clarity, more calm, and a deeper sense of understanding. But interestingly, that’s not what most clients are looking for at the start.

But both I and my clients have come to realize that the true value of facilitation lies in the states it creates, and in the subtle shifts it brings to human interaction. That's where the real impact is.

Clients usually say facilitation helps them get unstuck. Vague discussions become clear decisions.

This depends on their knowledge of and experience with facilitation. Some see it as a neutral person chairing a meeting, others talk about helping the participants hear and understand each other, share their perspectives, reach better decisions quicker, use creative approaches.

Taken together, these responses reveal a persistent (and frankly, a little alarming) communication gap in the field. Facilitators articulate value in terms of alignment, inclusion, clarity, and the deeper craft of designing productive group processes.

Clients, by contrast, tend to describe outcomes in more immediate and concrete terms: productive meetings, smoother discussions, decisions reached, or conflict eased. The impact they notice is real, but often described superficially.

Many facilitators wish people understood the underlying expertise and long-term impact of facilitation: how it shapes culture, prevents misalignment, improves decision quality, and creates the conditions for better collaboration. The gap between experienced impact and expressed value points to a core challenge for the field: the benefits of facilitation are widely felt, but not widely articulated. Until practitioners find more accessible, resonant ways to communicate their craft, the work will continue to be recognised in practice but underestimated in discourse.

Le temps nécessaire pour bien préparer et l'importance d'avoir un objectif clair.

(The time needed to prepare properly and the importance of having a clear goal).

If clients knew more about how facilitation works, it would be easy to partner on higher level agenda design with an already educated client rather than having to spend so much time teaching them how collaboration works.

It takes more time to prep than you think and unless you are doing surveys and interviews several months after training, you don't really know your impact.

Good facilitation isn’t just managing time and reading the room.

The real work starts long before anyone arrives, by asking the questions that shape the experience.

It’s designing the agenda, the activities, the structure, and the conversations to drive real outcomes.

It's structuring a process that thoughtfully democratizes input, filters ideas, and ensures the best thinking rises to the top.

It's harder than it looks

Que a facilitação pode ser aplicada no dia a dia da empresa e não só em momentos especiais (workshops).

(That facilitation can be applied in the day-to-day running of the company and not just at special times (workshops)).

In these responses we find practitioners pining for a world where facilitation skills are more widely understood, used, and valued. So, how do we get there? Some responses seem to point to way forward, hidden in the tension and apparent polarity between these two positions: “facilitation is for everyone” and “facilitation is a professional skill”. Let’s see what they say.

Facilitation is a basic skill anyone can and should learn

Representative respondent quotes:Facilitation is a professional craft that takes years to master

Representative respondent quotes:Many respondents argue that basic facilitation should be part of everyday working life — a shared capability that makes meetings clearer, conversations more inclusive, and teams more effective.

Others stress the opposite: that facilitation is a sophisticated professional discipline, requiring years of practice to navigate power dynamics, conflict, emotions, and complex group processes. Both perspectives are true.

Everyday facilitation skills are becoming more widely distributed, improving collaboration across organisations. At the same time, specialist facilitators bring a depth of expertise that enables groups to tackle high-stakes, ambiguous, or emotionally charged challenges. As more people gain some basic understanding of facilitation’s value, it becomes progressively easier to make space for the deeply trained professionals, when it’s really needed.

Therefore, the future of the field lies in holding both truths: raising the baseline while recognising and protecting the mastery.

The polarity surfaced in the survey—facilitation as a basic skill versus facilitation as a professional craft—is not a problem to be solved, but a tension to be held. The future of the field depends on our ability to do both well. As facilitation skills become more widely distributed, day-to-day collaboration improves. Meetings become clearer, conversations more inclusive, and teams more capable of working through differences.

At the same time, this very diffusion makes it easier for organisations to recognise when situations require professional mastery—when stakes are high, ambiguity is real, emotions are charged, and power dynamics are at play. In such moments, the need for a skilled and neutral facilitator cannot be underestimated.

The different perspectives highlighted in the survey are therefore not surprising. The words facilitation and facilitator can mean different things depending on experience, exposure, and context.

For some, facilitation is simply a way to run better meetings. For others, it is a disciplined practice that helps groups navigate complexity, conflict, and uncertainty in ways that would otherwise be difficult or impossible. The combination of a company-wide culture of facilitation with collaborations with external professionals is often a feature of organizations we’ve met in our work at FIA.

The IAF introduced the Facilitation Impact Awards (FIA) to honour organisations that have achieved a positive, measurable impact using facilitation. The word “impact” in this context refers to the organisational outcome achieved: the measurable ROI or results from using facilitation.

Nominations are evaluated against 8 criteria, including the extent to which:

Over the past 12 years, some 200 organisations in 35 countries have received awards at the Silver, Gold or Platinum level. What do these organizations have in common? In a nutshell, winning organizations are able to tell a clear and concise story about the impact they wanted to see and how they used facilitation to achieve it.

Key success factors include:

We know that all facilitation when done well creates inclusion and ownership amongst stakeholders and other intangible benefits. The Facilitation Impact Awards challenges organisations to step up and measure the results.

To learn more about how organisations have achieved a positive, measurable impact using facilitation, read the FIA awardee case studies at Facilitation Impact Awards.

Julia specialises in designing, facilitating and managing processes to help groups achieve their desired outcomes.

Together with her clients, she pioneered—some 24 years ago—the use of facilitation, design thinking and human-centred design to create better government regulatory experiences for citizens. She is a past chair of the IAF Global Board and was the Facilitation Impact Awards project lead for 8 years.

Shalaka currently serves on IAF's Global Board as the Director of Conferences and Events and is the project lead of the Facilitation Impact Awards.

A Psychology graduate and a Human Resource Management professional, she facilitates organizations to help them strategize and plan, align teams to organizational goals, improve collaboration between groups, innovate for better problem solving. She is a certified Flow Game host and facilitates Youth Leadership workshops through the United Nations Volunteers.

Julia Donohue and Shalaka Gundi – Facilitation Impact Awards team

As we near the end of this year’s report, let’s take a moment to check in and update our information on the hot topic of AI.

All hype aside, how are facilitators actually integrating AI in their workflows? What tools are they using, and for which tasks?

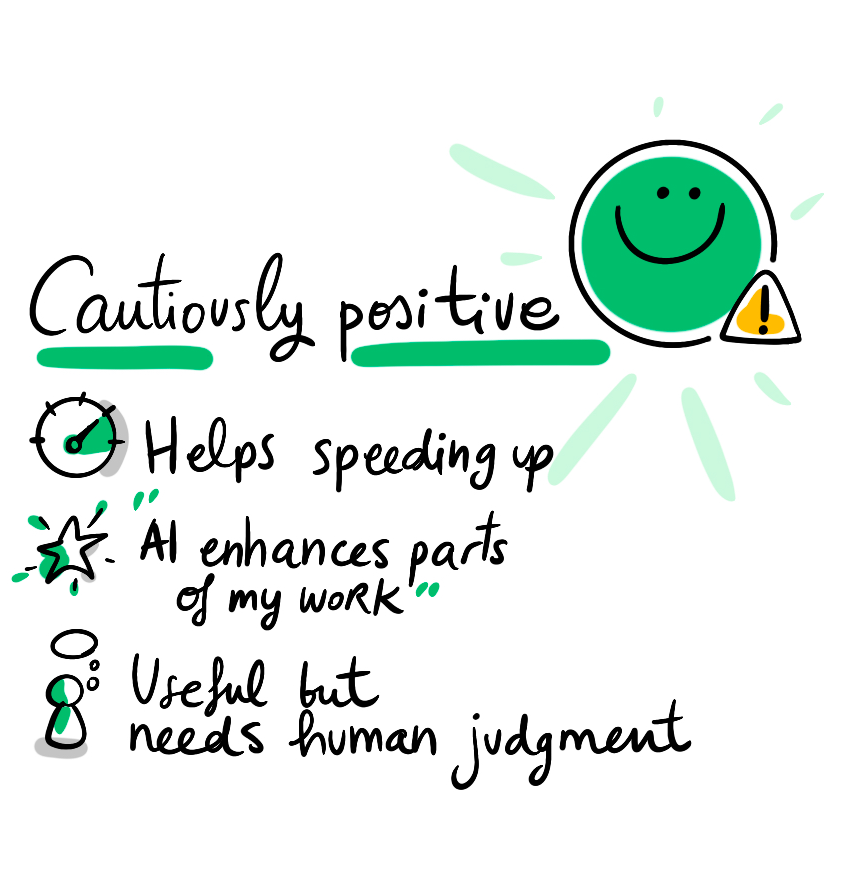

The biggest shift year-on-year is in the Often category, which nearly doubles, from 21.7% to 38.7%. This suggests that AI is no longer something facilitators are cautiously experimenting with: it’s becoming a regular part of their workflow.

The drop in Trying it out (from 27.5% to 20.6%) and Never (from 25.1% to 15.2%) indicates a movement along the adoption curve: fewer facilitators are beginners or sceptics, and more are establishing repeatable AI-powered practices.

Among facilitators already using AI, the landscape is still dominated by general-purpose tools rather than facilitation-specific ones. More than half of respondents rely on OpenAI’s ChatGPT, making it by far the most widely adopted AI assistant in the field.

Adoption of tools directly embedded in facilitation platforms remains modest. Adoption of Miro AI (17.9%), SessionLab AI (9.1%), and meeting assistants such as Fathom or Otter.ai (15.4%) indicate that facilitators are still in the early stages of integrating AI directly into their design and delivery environments.

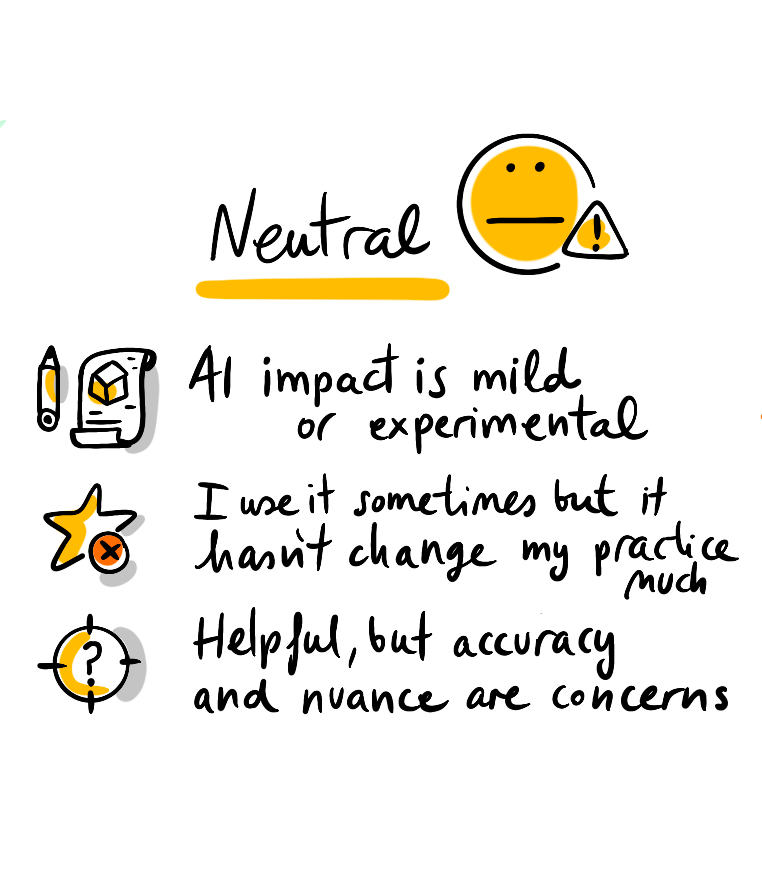

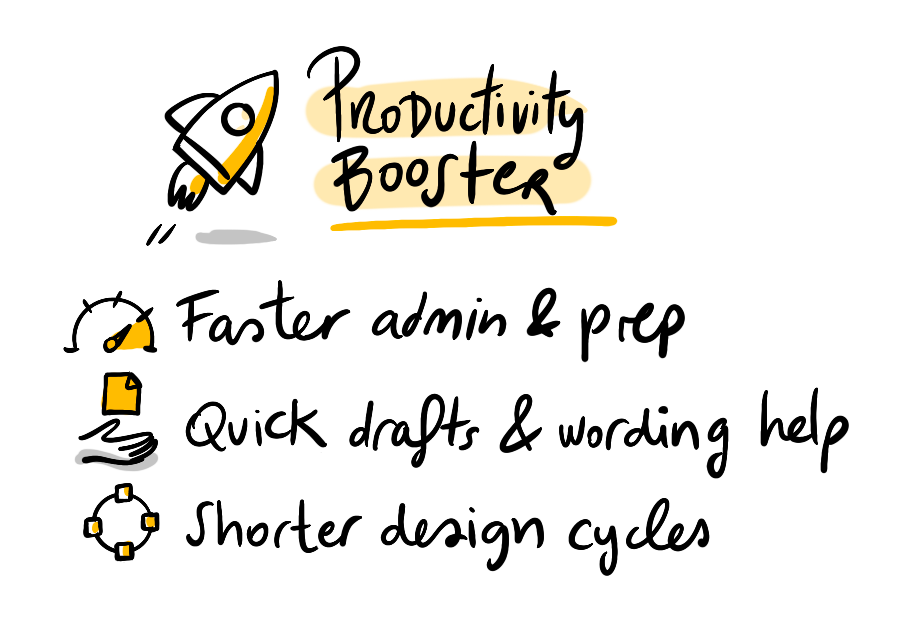

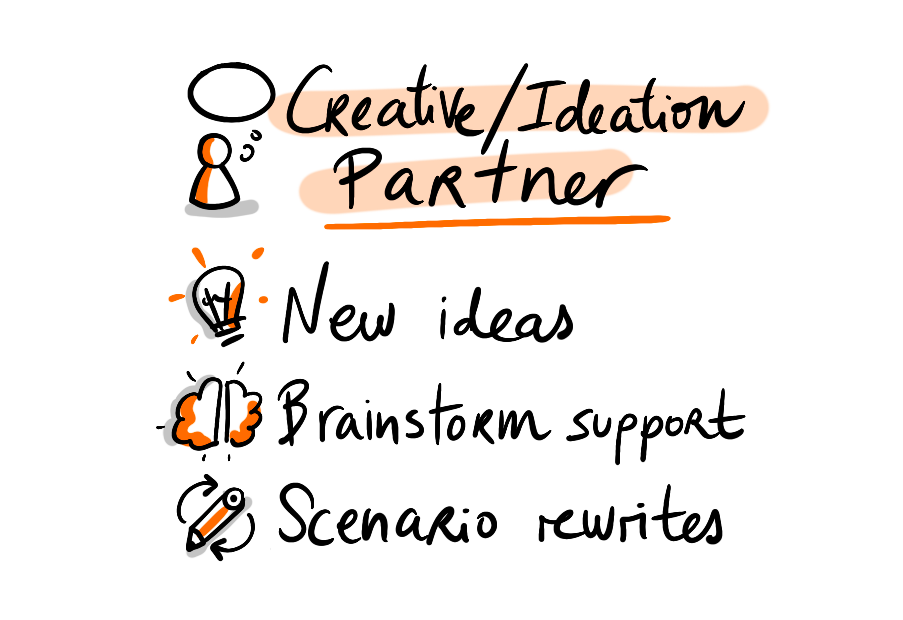

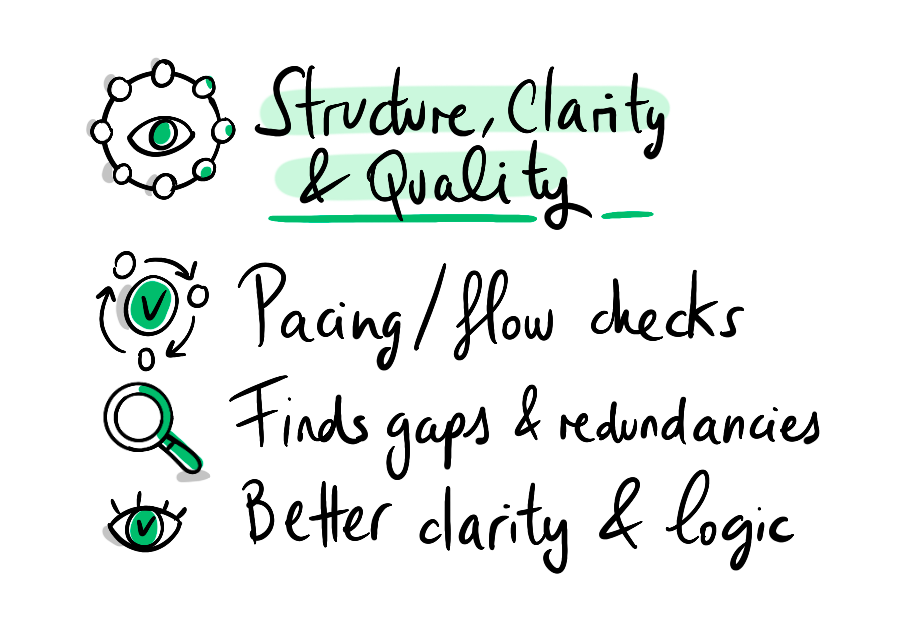

The sentiment analysis summarised below reflects a mostly cautiously positive approach. When asked how AI is impacting their facilitation work, practitioners write about it as a useful helper, but also note quite a few concerns about reliability.

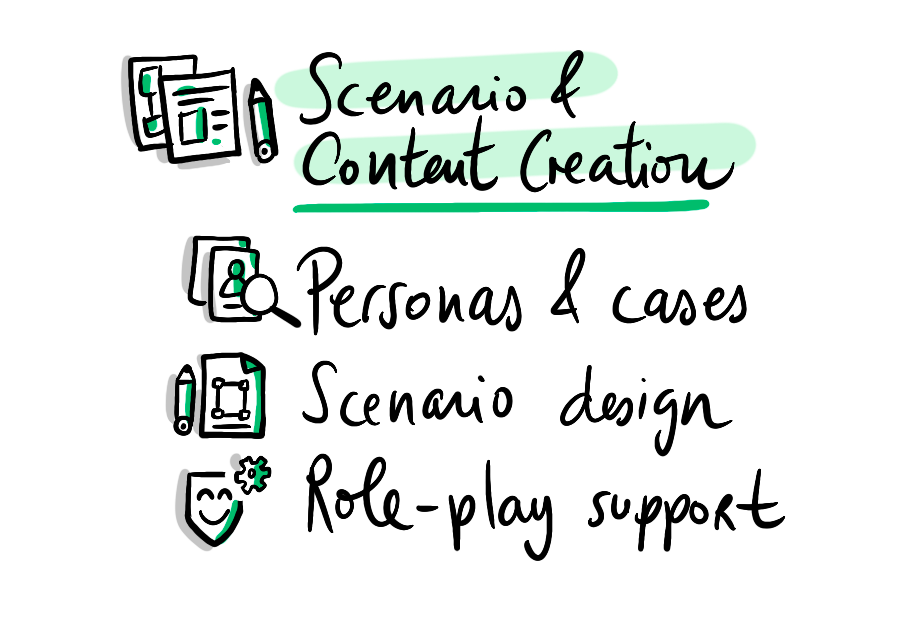

Correlating with what we’ve seen so far, session preparation (85.2%) is where most facilitators are actively using AI tools. We can combine this with data from the graph below, where we asked a more granular question about use-cases. Together, these clearly show that AI is strongest in the early design phase, as a thinking and brainstorming partner (generating ideas and brainstorming is the most common use-case, with 67.5% of facilitators using AI at this stage).

AI plays a meaningful role in post-workshop activities (53.9%) such as summarizing information and creating reports (31.3%).

Scenario creation for role play and scenario planning (51.6%) has emerged as a high-value use-case that is quite specific to facilitation.

Live facilitation use remains limited, but has risen from 19.6% last year to this year’s 23.5%.

Communication and promotional uses are secondary but certainly useful, freeing facilitator’s time from more marketing-oriented tasks such as crafting advertising materials and invitations to workshops (28.2%).

Responses to the open question “How is AI impacting your facilitation practice?” reflected a great diversity of opinions (and enthusiasm) in the field. We’ve clustered the main topics that emerged below.

The largest cluster of responses discusses AI as a productivity booster, helping with admin, prep, and drafts. AI is also often described as a creative partner, especially given how many facilitators are working alone.

Certain individual responses brought very specific use-cases, such as using AI to check for the accessibility of a specific session design, or to tailor content to a certain group of participants. Those tech-savvy pioneers who have very much embraced using AI in facilitation have a lot of ideas to share. In 2025, a number of training events and conferences were organized to do precisely that: we can see this continuing into 2026 and beyond.

It makes some of the repetitive and timeconsuming assignments easy and quick to complete, and sometimes gives ideas you would not think of.

It compensates the fact that i work alone and have less opportunity tò design sessions with other colleagues.

I use it to create mini courses to level up my knowledge in advanced techniques and sometimes around the client subjects and industry information.

I hear of non-facilitators using it for session design. I worry that the art of facilitation is being lost.

Makes transcribing Post-its so much easier!

It helps me generate materials that are much more tailored to participants' specific needs and context. They feel the session was designed specifically for them and their challenges.

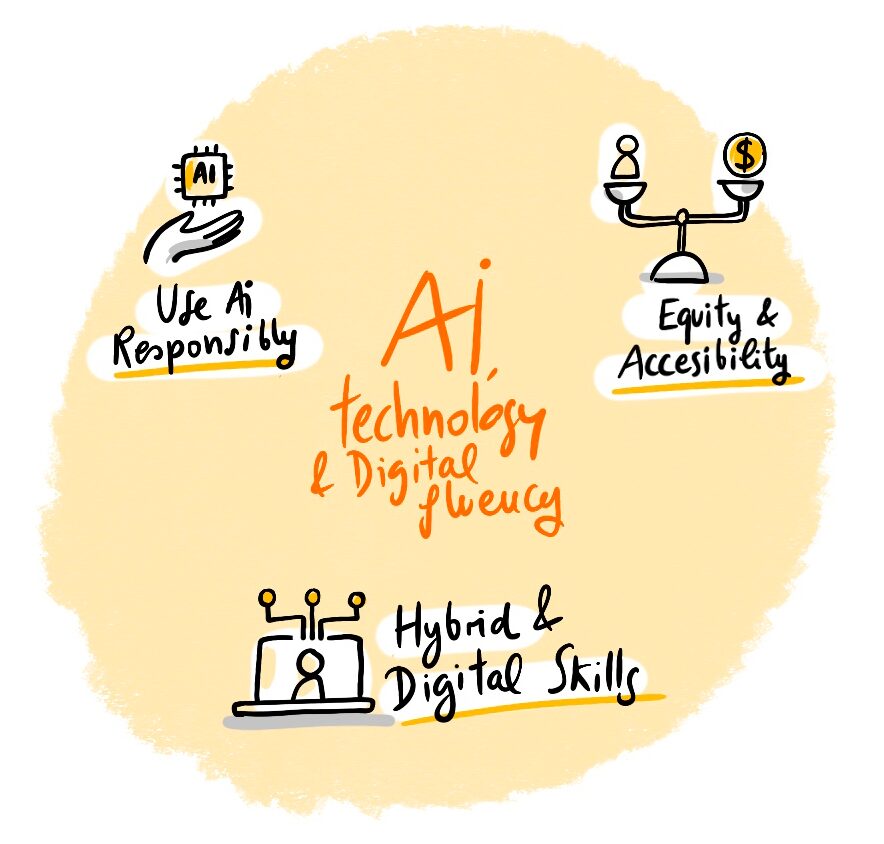

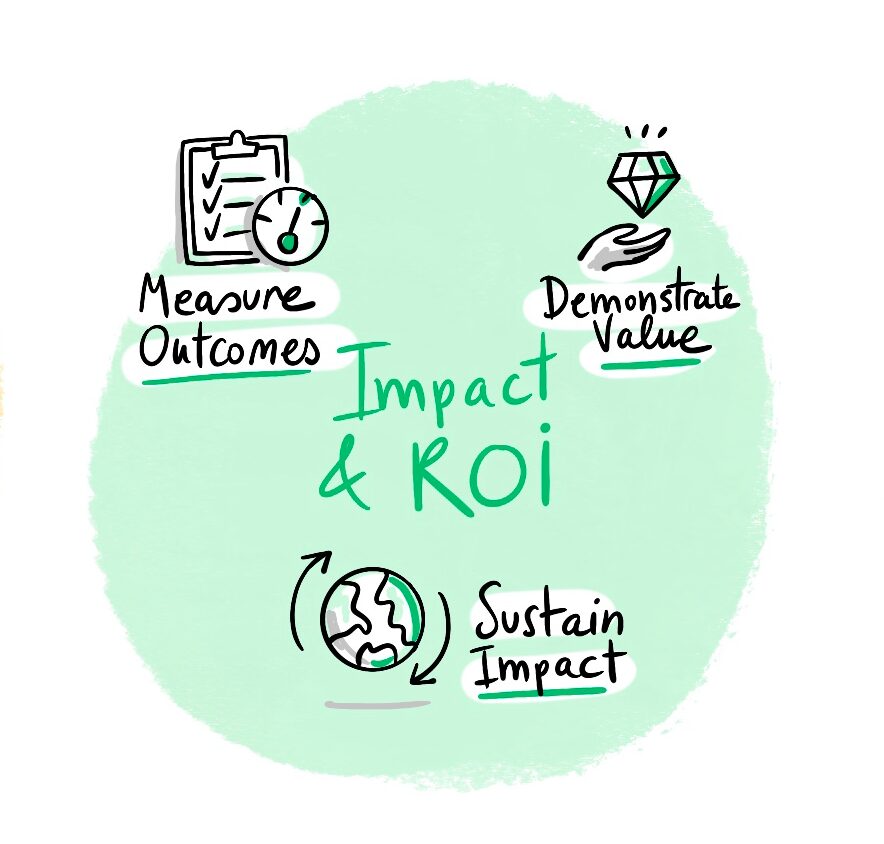

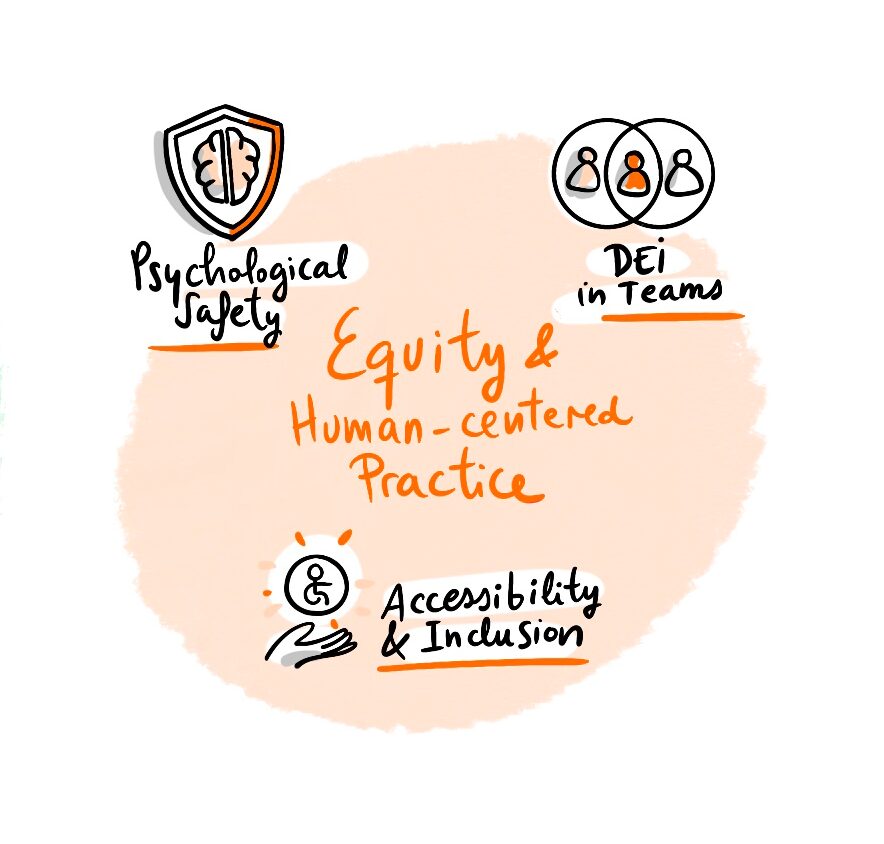

How to best make use of AI, and digital skills in general, featured high among responses to the last questions we’ve asked this year: What are the most important topics for facilitation to focus on going forward?

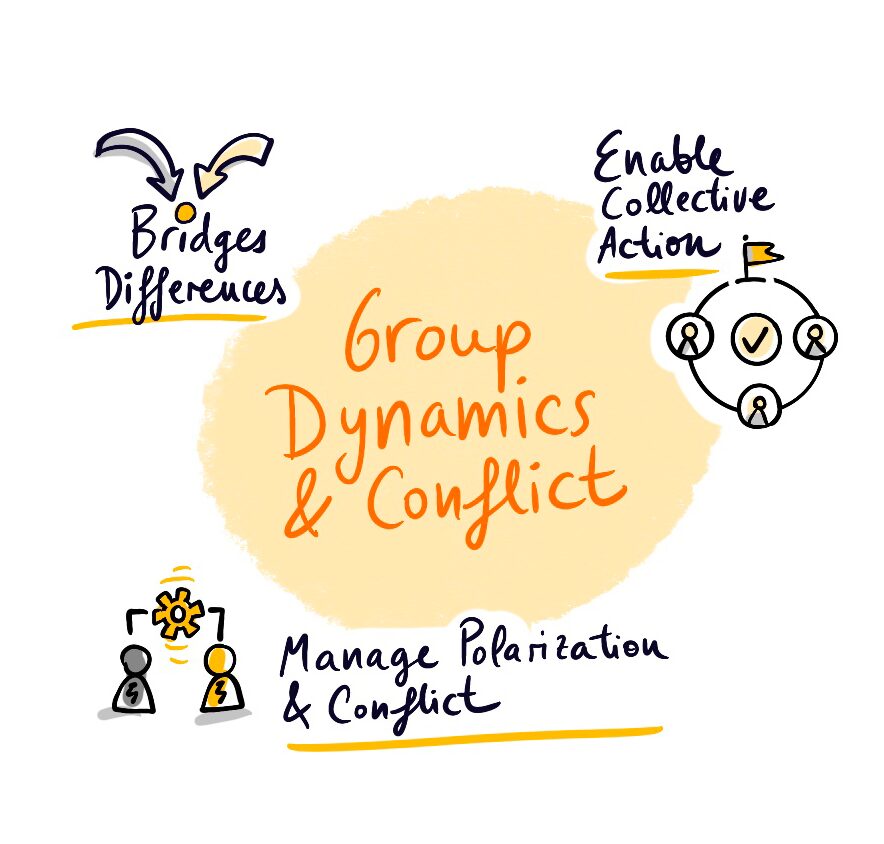

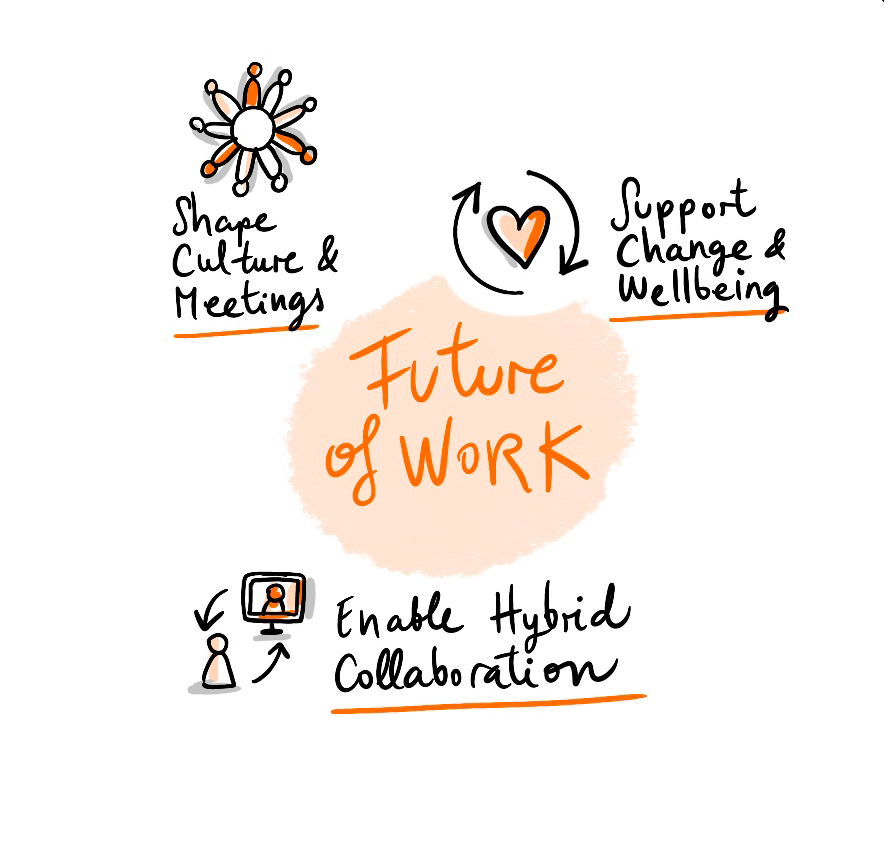

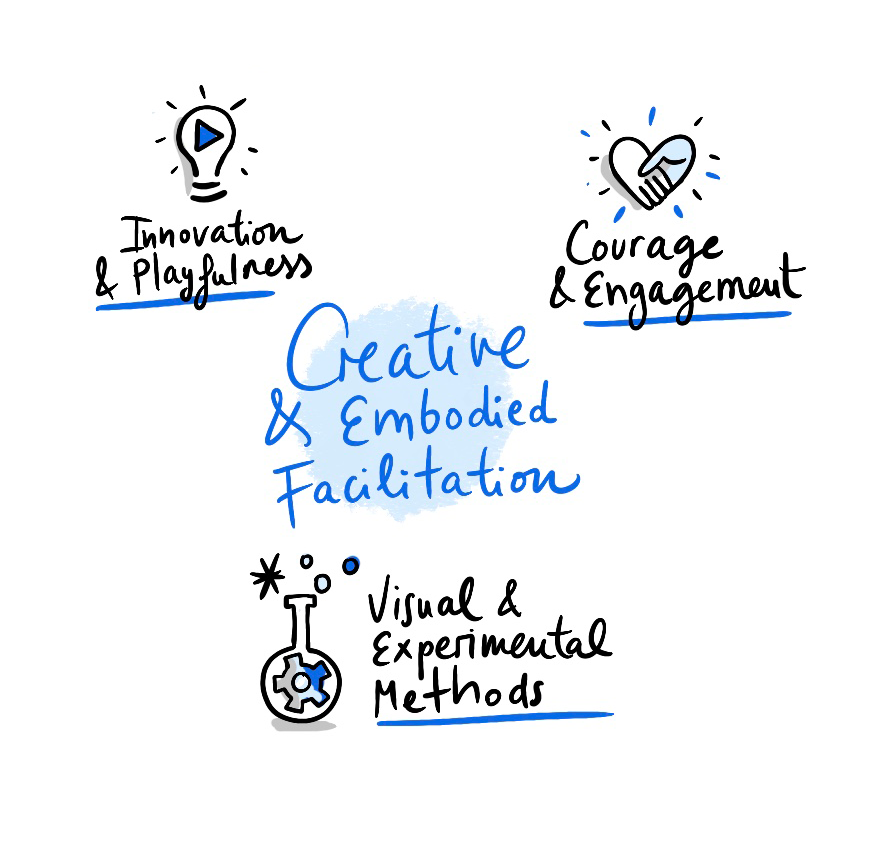

Below you’ll find a visual summary of responses.

Overall, these point toward a field negotiating both continuity and disruption. Facilitators want deeper grounding in human-centred practices (psychological safety, trauma-informed work, intercultural competence) while also expanding their ability to work with emerging technologies (AI, hybrid tools, digital fluency).

Another strong thread emphasises societal relevance — navigating polarization, supporting sustainable transitions, and holding spaces for dialogue at scale. The skills of the future, in this view, combine facilitation craft with leadership capacity, ethical awareness and technological literacy.

Participants don’t arrive at workshops ready to think.